These magnificent birds are related to emus and ostriches. And for such a large bird, cassowaries are known to be elusive, and potentially dangerous, in the tropical rainforests of South East Asia and Australia. Unfortunately, the species is declining and classified as vulnerable by the IUCN. At Chester Zoo we have two southern cassowaries which have recently been moved to our new Islands habitat.

Chester Zoo bird keeper, Zoe Sweetman, tells us more about these birds:

“The first thing you notice about the cassowary is their dinosaurlike features, they started to evolve over 60 million years ago during the Cretaceous period and they are still a very big intimidating bird. Cassowaries use a series of low frequency booms and calls to communicate. These signal their territories and breeding susceptibility, as well as many other things which we simply do not understand.

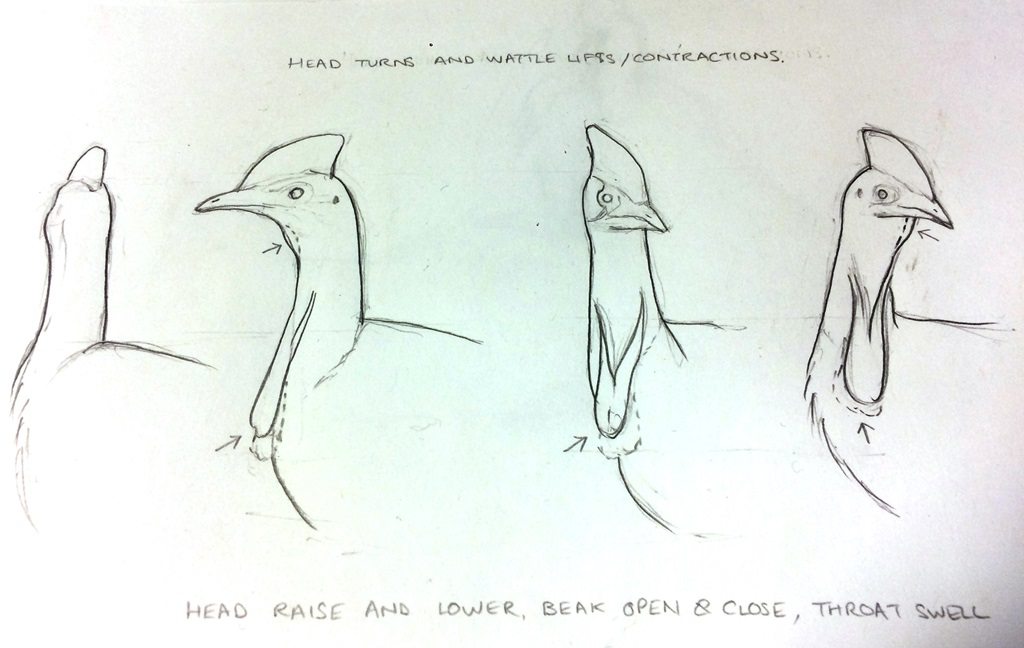

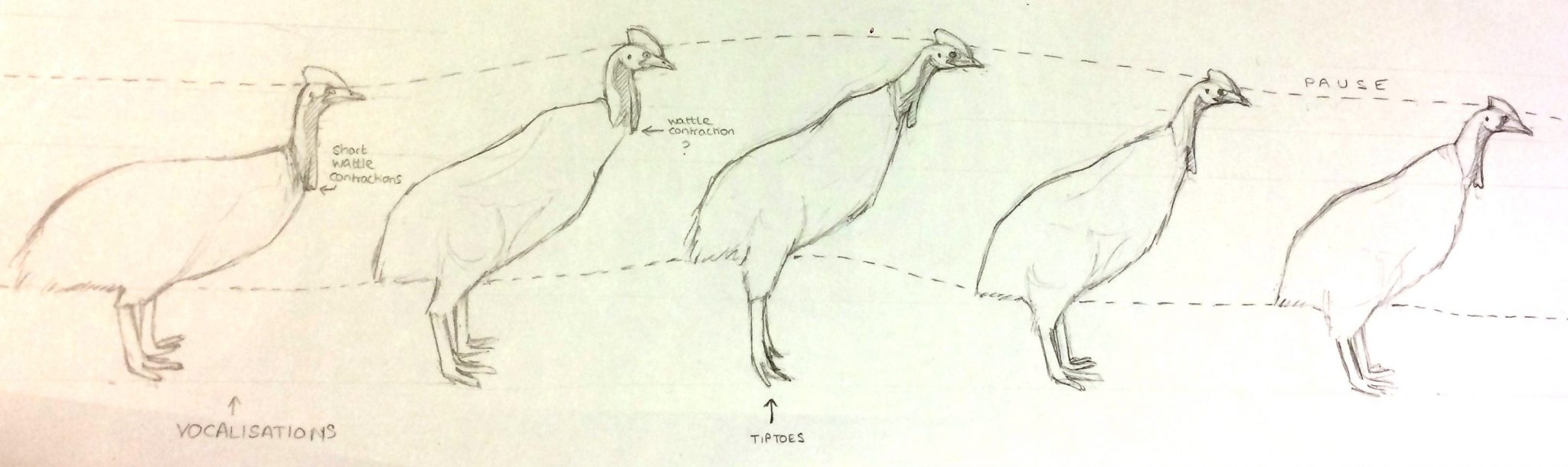

I find the subtle way in which they communicate with one another through body language very interesting indeed. The gentle head bobs and body brushes observed between our male and female are almost romantic and watching such a large and powerful bird behave in this elegant manner is absolutely fascinating.

“Although cassowaries are a shy and secretive bird, they can become very aggressive if they feel threatened. They have a long claw on the inside toe which they use to kick out and injure any potential threat including humans. This means that they are classified as a ‘category red’ species, so we can’t go in with them but our new enclosure has been fitted with lots of cameras giving us a brilliant insight into the cassowaries behaviour.

“Cassowaries are primarily a solitary species, however, it has always been our aim to try and introduce our pair. As cassowaries are notoriously difficult to mix, we needed to be able to watch their behaviour and body language towards one another for several weeks before we risked putting them together.

“Working alongside applied science staff at Chester Zoo the cassowary keepers have been investigating their breeding behaviour after they were mixed for the first time. Very little is documented about their behaviour and we are trying to change that. Using CCTV footage our scientists have been monitoring them and, for the first time, their reproductive hormones from faecal samples have been analysed in Chester Zoo’s endocrinology laboratory. We are planning to expand this research further by recording their low frequency booms and calls, some of which we believe are outside human hearing.”