The next in our series of studentship blogs is an update from Lydia Murphy, whose research focused around the red squirrel and the pine marten – two of the UK’s most iconic species!

Below she explains in more detail exactly what she was researching and what she had to say about the experience:

“For my MSc research project I was working with the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust, studying the ecological and social aspects of managing woodlands for two of the UK’s rarest mammal species: red squirrels and pine martens.

“Why red squirrels, and why woodlands? Well, in the last half-century red squirrel populations in the UK have decreased dramatically – whilst once common all over the British Isles, today they can only be found in northern and central Scotland, and in some other isolated pockets.

“The red squirrel’s demise is largely attributed to the spread of the invasive non-native American grey squirrel. One of the tactics used by conservationists to preserve the remaining red squirrel strongholds is to manage woodlands to create the best possible habitat for reds.

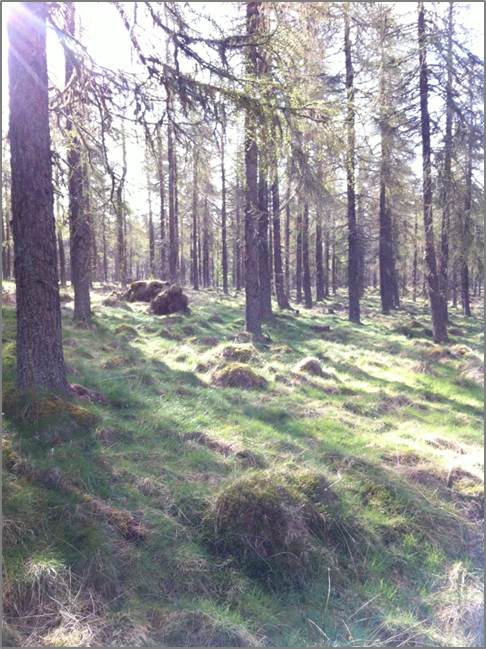

“I was based in Aberdeenshire, in a region east of the Cairngorms National Park known as the Howe of Cromar. This area is known to have a healthy population of red squirrels, but with grey squirrels not far off the horizon, it is important to make sure that the woodlands in the Howe of Cromar are managed appropriately so that the red squirrel population can thrive. Therefore, for my research project, I wanted to find out what sorts of woodland habitat red squirrels favour in the area, so that the estate managers in the Howe of Cromar could know how best to manage their woodlands for red squirrels.

“How do pine martens fit in? Pine martens are carnivores, a member of the weasel family, and may play a pivotal role in red squirrel conservation!

“Research carried out by Emma Sheehy at the National University of Ireland showed that:

1) pine martens eat grey squirrels and

2) in areas of Ireland where pine marten numbers had recovered, grey squirrel populations had crashed and red squirrels had re-colonised woodlands.

“What this suggests is that encouraging pine martens could prove a viable means of controlling grey squirrels – and thus helping reds. However, there are still lots of factors to consider – for instance, pine martens are known to prey on red squirrels elsewhere in Europe. Although British pine martens seem to prefer other prey over red squirrels, for my research project I wanted to find out whether presence of pine martens in woodlands was having any effect on red squirrel numbers.

“Supported by Chester Zoo and my other funders, I spent three months in Scotland gathering data for my project. Finding red squirrels sometimes proved tricky, as they are nervous animals and tend to hide if they sense a human approaching.

“At times it felt more like a game of hide-and-seek than an ecological survey! Thankfully, I did manage to catch the odd one poking its head out from behind a tree trunk to inspect me and my binoculars. Pine martens also proved adept at hide-and-seek, but with time (and a lot of peanut butter) they started to poke their noses into my equipment, with some great photographic results. Chester Zoo helped fund the materials I needed for my pine marten survey equipment, which proved invaluable in luring these notoriously elusive animals within range of my camera-traps!

“In between counting squirrels and pine martens, I chatted to the estate managers, whose woodlands I was surveying, to find out whether they thought managing their woodlands to favour red squirrels and pine martens was possible. As the people in the area with the means to make changes in woodland management to benefit red squirrels and pine martens, it was important to understand how they thought conservation of these species could (or could not) fit into their existing woodland management plans. And while there were some ways in which managers felt red squirrel and pine marten woodland management could be fitted in alongside their current activities, many conservation actions for these species were perceived to clash with existing activities or policies. For example, while it is recommended to leave wind-blown trees in place as denning and shelter sites for pine martens, managers were accustomed to removing them and selling them as timber.

“Incongruences between wildlife habitat and human management activities were also indicated in my ecological results, which showed that fewer red squirrels were found in older woodlands where the trees had been thinned out in preparation for harvesting, and more were found in woodlands where livestock exclusion and natural regeneration had allowed an understory layer to develop. The pine martens at my sites didn’t seem to be having an adverse effect on red squirrel populations, lending support to their potential use as a grey squirrel control agent.

“So all in all for red squirrel conservation in the Howe of Cromar: while pine martens may prove a help, not a hindrance, there is still work to be done to find ways of managing woodlands for red squirrels, pine martens, and humans, where all three species can benefit. The work carried out during this project provides a useful starting point for constructive dialogue between conservationists and landowners in the region.

“Many thanks to Chester Zoo for all their support, and for helping me to study some of the amazing wildlife we have here in the UK!”