Tag: Animal health and wellbeing

We’re working with zoos around the globe, international conservationists and the Indonesian government to support Asian wild cattle conservation in South East Asia. This is the first time the global community has joined forces with the Indonesian government to share expertise and resources for the conservation of banteng, anoa and babirusa.

All these wild cattle species are threatened with extinction and together we want to reverse the dramatic decline in their population numbers.

It’s important that we share our expertise with other zoos and conservation projects around the world; strengthening the connection between the work being done in zoos and in the wild.

We have an active partnership with the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) Asian Wild Cattle Specialist Group (AWCSG) – focusing mainly on the anoa, babirusa and banteng – which is made up of field experts, including conservationists, biologists and zoo professionals. The group is committed to sharing information, research results and conservation experience of Asian wild cattle.

Our South East Asia programme coordinator and programme officer of the Asian Wild Cattle Specialist Group, Johanna Rode-Margono, recently spent time in Indonesia with Chester Zoo’s curator of mammals, Tim Rowlands.

The main objective of their trip was to strengthen our relationship further with other zoos in Indonesia and promote the importance of cooperative conservation breeding programmes in helping to save the three species; as well as finding opportunities to assist in building on husbandry practices and education activities.

Johanna tells us more:

The babirusa, anoa and banteng are all threatened with extinction mainly due to hunting and habitat loss – like human encroachment, plantations or mining. So any work being done to help protect them is vital.

“Chester Zoo is one of the leaders in the conservation breeding of anoa, babirusa and banteng, our experts have important skills and knowledge that they can share and collaborate with others to ensure the survival of these animals before we lose them forever.

“By making sure there is a viable global population of these species in zoos, whose genetic diversity represents the genetic diversity in the wild, the global zoo community can play a vital role in saving them.”

Tim and Johanna spent time meeting other experts at seven Indonesian zoos to look at their husbandry practices and their current facilities in order to prepare an intensive keeper training workshop in 2017.

Tim explains:

Many zoos in Indonesia are already doing great work with keeping and breeding anoa, babirusa and banteng; but some still keep them in relatively basic conditions. Cooperative conservation breeding between zoos in Indonesia has not been done intensively, partly due to lack of facilities but also the lack of understanding of the benefits it can bring to the species as a whole.

“It takes time and diplomatic discussions to explain to some Indonesian zoos the bigger picture and how conservation breeding is an important part of saving endangered species. But it’s worth the effort.”

Johanna and James Burton, chair of the AWCSG, also conducted surveys on the islands of Sulawesi and Java, to find potential location for future in-situ field projects. Together with the AWCSG, Chester Zoo wants to develop several long-term field projects in South East Asia that contribute directly to the conservation of the species in the wild.

The surveys will continue over the next few months to ensure the greatest impact and next year we aim to start a new project.

Johanna continues:

“We have not seen any wild anoa and babirusa. Apart from the fact that they are elusive and rare species, by talking to conservation authorities and local people we got the feeling populations are declining fast. It is time to act! In contrast, we have been lucky enough to see banteng in some National Parks. Although just a few hundred are left, we could observe around 70 animals in one grazing ground. This was a very emotional moment for the team.”

We’re looking ahead to the new year – when we will be running training workshops on facility design and animal husbandry in Indonesian zoos. Tim will be leading these activities sharing the extensive skills he has developed through working at Chester Zoo; sharing them to help the global conservation of anoa, banteng and babirusa.

Keep an eye on our blog for more updates about our conservation work with Asian wild cattle.

Our amphibian programme focuses on the most endangered vertebrate group in the animal kingdom, with more than a third of the 6600 known species threatened with extinction. Addressing their extinction crisis is thought to be one of the greatest conservation challenges ever faced but it is something we’re attempting to tackle by working closely with our partners.

A high priority for us is the protection of one particular amphibious species; the critically endangered mountain chicken frog. It is estimated that there is less than 50 individuals left on the Caribbean islands of Montserrat and Dominica.

Similarly to many amphibian species around the globe, the fungal disease chytridmycosis is one of the main threats to the mountain chicken frog – there is currently no cure and it is very difficult to control its spread. The mountain chicken is also seriously threatened by their use as a food source for local people.

We are part of an international campaign which aims to save this species and build up numbers on these islands before it’s too late. We are working on both in-situ and ex-situ projects, including a breeding and research programme, trialling the release of young adult frogs onto the island of Montserrat.

We are also the coordinator of the captive management population of this species and are working with universities and conservation scientists to carry out research, much of which is done in specially built laboratories here at the zoo.

Unfortunately, the population numbers are currently worrying low and as a result we hosted a critical meeting to discuss the long-term management plan for the mountain chicken.

Facilitated by Kristine Schad, population biologist for the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA), we welcomed a number of conservation scientists with the aim of setting roles and goals to ensure that the population gets back on track.

Other participants include our curator of lower vertebrates and invertebrates, Gerardo Garcia, Ben Baker, Pip Carter-Jones and Katie Upton from Chester Zoo, Benjamin Tapley from ZSL, Matthias Goetz, Durrell Zoo and Natalia D’Souza, Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology at the University of Kent.

We’ll keep you up to date with the project and any future developments resulting from the meeting.

We’re working in collaboration with other zoos to help save this critically endangered species through a breeding programme before it’s too late; the first of its kind to focus on amphibians.

Twenty four frogs have been carefully matched together using detailed genetic information in a new breeding effort which is seen as the last hope for the long-term survival of the species.

Together with Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust in the UK and Norden Ark in Sweden, we aim to ensure a genetically viable population of the frogs kept in bio-secure conditions which, one day, could see them reintroduced into the wild.

Only a small number of wild mountain chicken frogs remain on just two islands, Dominica and Montserrat – with Montserrat now home to just two individuals, one male and one female!

Dr Gerardo Garcia, curator of lower vertebrates and invertebrates at Chester Zoo and studbook holder for the mountain chicken breeding programme, tells us more below:

“Essentially we’ve created a dating agency for one of the largest and most endangered frog species in the world. Based on genetic evidence and DNA sampling we’ve matched together the best pairs of mountain chicken frogs from the four institutions in Europe that work with them – to try and breed the most genetically viable population of the frogs that we possibly can.

“Our ultimate aim is to reintroduce these wonderful animals back into the wild where, sadly, their numbers have been completely decimated. To do that we need a long-term sustainable breeding programme and this is the first and only European Endangered Species Programme (EEP) for an amphibian, so it’s a real landmark plan that we’ve developed. The frogs are spiralling closer and closer to extinction – so it really is do or die for them.

“Protecting mountain chicken frogs is incredibly important to conservationists. These frogs are the top terrestrial predator on the Caribbean islands where they live and crucial to the control of pests and insects. They have a key role in the eco-system and their disappearance could potentially have an impact on crops and, subsequently, livelihoods. These frogs have also always been culturally important to the islands.

“Mountain chickens are incredibly charismatic and there’s no other species that’s like them. However, what we’re doing to try and protect them is not just about this species, as what is learnt here can be applied to others in the future. Right now we have no idea just how valuable this work could be.”

Population biologist at the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA), Kristine Schad, said:

“This spectacular species is on the very brink of extinction, so the skills in the zoo community represent one of the last chances for its survival. The creation of a monitoring breeding programme for the mountain chicken frog is hugely important if we are to avert disaster for the species.”

We’re also working with a number of universities and researchers to carry out studies on the species, much of which is done in in three purpose-built labs at Chester Zoo. To find out more about the work we’re doing with mountain chickens, read some of our previous blogs here.

To help us continue our vital work to stop this animal from going extinct, please make an online donation here – or text ‘AMPH18 £5′ to 70070 to donate £5 to our amphibian programme.

- £5 will feed the mountain chicken frogs at the zoo for one day

- £30 will buy a portable pool for baby frogs

- £100 will fund a rearing room for mountain chicken babies – fingers crossed we’ll need these in the near future!

(JustTextGiving by Vodafone. For full T&C’s please visit Just Giving)

Amphibians have been treated in the wild for the first time against the global chytridiomycosis (‘chytrid’) pandemic currently devastating their populations worldwide, as part of a pioneering study involving conservation scientists from Chester Zoo.

Published in the journal Biological Conservation and conducted in partnership with the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, the University of Kent and the Government of Montserrat, the paper describes how the established antifungal drug itraconazole can be used to treat amphibians in the wild during periods of particular risk from chytrid outbreaks.

Frogs were individually washed for five minutes at a time in a bag containing the anti-fungal bath. While this measure was not ultimately able to stop them dying, the paper demonstrates that this technique has potential to greatly extend the likely time to extinction for any given amphibian population in the face of epidemic disease.

Caused by the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), this chytrid variant has so far infected more than 600 amphibian species globally – causing population declines, extirpations or extinctions in over 200 of these and representing the greatest disease-driven loss of biodiversity ever recorded. Whilst captive breeding programmes offer hope for some, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently estimates that even with the cooperation of the global zoological community, only around 50 species could potentially be saved from extinction through this approach. Proven, field-based methods will therefore play a vital role in mitigating the risk posed by this disease.

Commenting on the paper, lead author Michael Hudson – jointly based at ZSL’s Institute of Zoology (IoZ), Durrell and the University of Kent – said:

“This method represents a valuable addition to the currently sparse toolkit available to conservation scientists who are trying to combat the spread of chytrid in the wild. The treatment explored in this paper could be used to buy precious time in which to implement additional protective measures for at-risk amphibian species.”

The study, funded by the People’s Trust for Endangered Species (PTES) and the Balcombe Trust, was based on ZSL and Durrell’s long-standing work with the ‘mountain chicken’ (Leptodactylus fallax). This critically endangered species, one of the largest frogs in the world, lives exclusively on the islands of Dominica and Montserrat in the Eastern Caribbean.

Expanding on the study, PTES Grants Manager Nida Al-Fulaij said:

“This latest breakthrough provides conservationists with an additional weapon in the global fight against amphibian chytridiomycosis. We’re pleased to be supporting this vital work as part of our wider mission to conserve vulnerable wildlife in the UK and beyond.”

Read this blog update from Chester Zoo herpetology keeper,explaining the critical situation many frog species are currently facing and the important role zoos play in helping to protect these critically endangered animals in the wild.

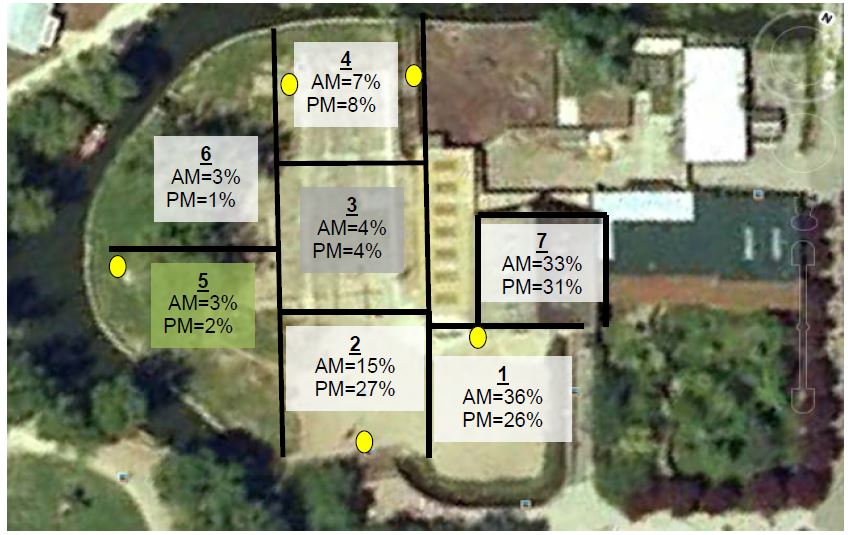

We want to encourage as many natural behaviours in our zoo animals as possible. We’ve been studying the behaviours of our Rothschild’s giraffes and how they use their paddock. In the wild, Rothschild’s giraffes have specialised diets which means they will spend large quantities of their time grazing and moving from place to place.

During the summer months, our herd of Rothschild’s giraffes have 24 hour access to their outdoor paddock. However, we did not know how they used the space or if the different giraffes had preferences for where they spent the majority of their time.

To better understand our herd’s behaviour and help the animal care staff make husbandry decisions, we recorded individual behaviour and movement during the day and the night using infra-red cameras to film activity levels and determine how the giraffes use the paddock.

We found that all our giraffe’s used the paddock at night and over the course of the day, the majority of time was spent in areas where food was available.

Throughout winter the areas the giraffes used the least tended to be those with a wet ground, which may have discouraged the giraffes from moving there. So, as a result of this project, the animal care staff considered the option to lay sand over the wet areas and offer more browsing opportunities to encourage use of the full paddock all year round.

Studies like this are important to help our animal teams make important husbandry decisions, based on scientific evidence, to promote the natural behaviours our animals would display in the wild.

Discover more about the work we do behind the scenes at Chester Zoo to understand more about animal behaviour.

Helen Pople is a science research master’s student, at The University of Portsmouth and another student whose research we helped through our Studentship programme.

Little research has been carried out on proboscis monkey behaviour – here Helen tells us more about the work she has been doing around this species and how they are affected by humans in the Lower Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary.

“In February 2014, I flew to Malaysian Borneo in order to carry out behavioural research on the endangered proboscis monkey. My work focuses on understanding the effects of humans on wild proboscis monkey behaviour and whether unregulated tourism can induce stress and other negative behaviours. I’ve always been interested in animal behaviour and jumped at the chance to study primates in the wild.

“The endangered proboscis monkey is endemic to the island of Borneo; living along forest edges and waterways, feeding off and sleeping in the trees along riverbanks.

“Around 60,500 tourists visit the Lower Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary each year and enjoy boat tours hoping to catch a glimpse of the monkeys. This, combined with the abundance of many other species, suggests that such a place needs strong regulations for tourism. In studies on proboscis monkeys it is clear that they are affected by human presence; they often flee when researchers or tourists get too close. We decided that it was important to further our understanding on how humans can negatively affect proboscis monkey behaviour.

“The results could be used to propose guidelines for tourism such as a set distance and speed limits that tour boats must obey when approaching the proboscis monkeys, and limitations on the times of day for boat tours. Whilst tourism creates essential revenue for conservation, it is important that we do not negatively affect wildlife in the process.

“Very little research has been carried out on proboscis monkey behaviour so the second part of my study aimed to find out more about proboscis monkey behaviours in general.

“In order to complete my research I was stationed at the Danau Girang Field Centre, positioned in the middle of the jungle, with a half an hour boat journey along the Kinabatangan River to the nearest town. I used satellite-tracking techniques to find the proboscis groups, who had already been safely collared by researchers at the Danau Girang Field Centre (another project that Chester Zoo works with).

Understanding behaviour

“A typical day involved waking up at 4.30am to set off in the boat and find the groups at 5.00am before it got light. By locating the groups the previous evening we were able to arrive very slowly in the dark and wait for the group to wake up without disturbing them. I would then film the individuals in the group one by one from the opposite bank for around two hours to get a general understanding of behaviour. In the afternoon we would head out again to find a new troop of proboscis monkeys and complete a boat approach experiment before dark. This involved changing the speeds and proximity of the boat and filming the proboscis monkeys at the same time.

“Whilst we are still in the process of analysing the results, just from observations it seems that proboscis monkeys are indeed negatively affected when boats get too close or are too fast. Once the results are analysed, a report will be written up and sent to the wildlife department of Borneo. We hope to use these results to suggest stronger rules for improving tourism and to protect our wildlife while we all continue to enjoy the environment.”

Photo credit: Tim Garvey

We recently introduced you to the science work we do here at Chester Zoo – and told you about our own endocrinology lab where we monitor our animal’s hormones. We also mentioned that we don’t just analyse our own animal’s hormones, we also work with other scientists conducting hormone analysis for their research in wild animals.

We’ve been working with scientists from the University of Exeter for a number of years on their banded mongoose research project. Banded mongooses are a close relative of the meerkat and are found across Central and Eastern Africa. They live in large, social groups between five and 40 individuals. The mongooses studied in this project are in Uganda and have been studied by researchers from the university for over 20 years.

Young mongoose in Uganda. Photo credit: Jennifer Sanderson

A recent study has investigated the effects of stress on banded mongoose mothers and the survival of their pups. Banded mongooses live in social groups with some individuals more dominant than others, this causes competition between females within the group. Banded mongoose females usually get pregnant at the same time and give birth on the same day.

This study used ultrasound machines to study the pregnant females and faecal samples were collected and analysed at our endocrinology lab. Researchers found that when a banded mongoose invests heavily to care for mongoose pups it experiences an increase in circulating stress hormones or ‘glucocorticoids’. These high stress levels meant that their pups were less likely to survive.

Jennifer Sanderson observes the behaviour of wild banded mongoose in Uganda. Photo credit: Faye Thompson

It could be that the dominant females may be stressing out the lower ranking ones during pregnancy to potentially increase the chances of their own pups surviving. This study shows that even though it appears that the mongooses are breeding cooperatively, that in fact the females are subtly competing with each other, and being a low ranking females can affect pup development.

This study was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and European Research Council (ERC).

L. Sanderson, H. J. Nichols, H. H. Marshall, E. I. K. Vitikainen, F. J. Thompson, S. L. Walker, M. A. Cant, A. J. Young (2015) Elevated glucocorticoid concentrations during gestation predict reduced reproductive success in subordinate female banded mongooses. Biology Letters 11, 20150620

At Chester Zoo, we house a vast number of reptiles that, unlike mammals, cannot maintain their own body temperature and must rely on their environment for thermoregulation – the process that allows the body to maintain its core internal temperature.

Therefore, it’s important that we provide the most effective way for our animals to obtain the heat that they need to remain healthy. Here at the zoo, we conducted a study to evaluate how well heat panels and smaller spot lamps provide heat for three species of reptile; Komodo dragons, Galapagos tortoises and red tailed racers.

Using a thermal imaging camera, which uses colour to display temperature, and a laser pointer thermometer, the heat distribution over the animals’ bodies was recorded. Alongside this, we used cameras to watch our animals’ basking behaviour under each of the different lamps.

We found that for the larger reptiles – such as the Komodo dragon – spot lamps, which are commonly used in zoo collections, did not provide effective heat coverage over the entire body length, in comparison to the heat panels. For smaller species however, the spot lamps were sufficient. Following the research and using this information from our results, we have made changes to the heat provisions for each reptile species.

Images from the thermal imaging camera

Studies like this are important to the zoo as they use scientific evidence to help our keepers provide the best husbandry for all our animals!

Winny Pramesywari is currently on a three month work placement here in the UK. Along with fellow veterinarian Siska Sulistyo, she aims to gain more knowledge and skills that will enable her to enhance her role at Sumatra.

Winny works at the Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Project (a project supported by Chester Zoo) in the quarantine centre. Below she tells us more about her day to day work and her journey on becoming a vet:

“A nine-year old girl was standing in front of a calendar. Her eyes were staring at pictures of wildlife on each page of the calendar, every detail was read carefully.

“Pa, what picture is it?” she asked her father, pointing to a panda image on the corner of the calendar sheet.

“It is the logo of an organization that works to save these animals from extinction” explained her father.

“Wooww! What should I do to help them?”

“You can donate your money so they can continue their work.”

“I don’t have money. What else can I do?”

“Well…you can be someone with the skills they need, such as a veterinarian”

“OK then. I will be a vet.”

“And here I am now – becoming a WILDLIFE VET, reaching my childhood dream!

“It was not easy! Veterinarian (at that time) was not a prestigious profession in Indonesia. Many people frowned and questioned my dream. I keep insisting, as my parent said ‘be whatever you want as long as useful for other living beings’.

“I chose to study at Bogor Agricultural University, one of the best Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in the country. Yet, I realized that I wouldn’t get enough knowledge of wildlife from education alone. Therefore during holiday breaks I became a volunteer on various wildlife rescue centres and zoos in Java and Sumatra to gain more knowledge that I need as a wildlife vet.

“I also joined conservation-based student activity at the university named Uni Konservasi Fauna (Fauna Conservation Union). Many different science-based students who are concerned with conservation gather and share the knowledge.

“I learned a lot of important things from them. We also did the observations of various wildlifes in their natural habitats, spent days or weeks in the forest. It’s quite amazing to see them in the wild. I believed a deeper knowledge and understanding of animal natural behaviour will be very much needed in my future field work.

“It was my graduation at the end of 2009 – I became a vet and was very excited! Unexpectedly, a month later I got a call from my friend, who worked at the Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Project (SOCP). He asked me to join them at the orangutan release site at Bukit Tiga Puluh National Park, Jambi. My dream comes true!

“Welcome to the world of conservation!

“I became the only vet in the program with the field-based project in the remote Sumatra forest. Since it was founded in 2002, Sumatran Orangutan Release Centre have released 160 orangutans. Usually there are 10-15 captive orangutans in rehabilitation waiting for their release.

“My main responsibility is to maintain the health of both captive and released orangutans as well as treat any ill or injured orangutans. My favourite areas of work are nutrition and behaviour. To arrange a proper and balance diet for captive orangutans (as well as supportive diet for released one if really needed) is so much fun and can be challenging.

“Observing their behaviour is also very fascinating and makes me amazed at how smart they are. Knowing this gentle and lovely creature more makes me fall in love again and again. I can feel their emotions through their eyes, it really melts me inside.

Observing juvenile orangutans during Forest School. Photo credit: Winny Pramesywari.

“Sometimes my work feels like a vacation. Challenging roads, limited access of communication (need to climb the hills to receive phone signal!), lack of electricity (only four hours a day, sometimes less!), meeting many new people and various wildlife, face different clinical cases, and rescuing wildlife are the sweet and bitter parts of my job.

“I nearly met a tiger while tracking released orangutans, and to hear its snarls really gave me the creeps. My friends even met wild elephants and a bear! But the best part of my job is the moment when I see orangutans free after our help. It is a relief.

Very challenging road to reach Sumatran Orangutan Release Centre at Bukit Tiga Puluh National Park. Photo credit: Winny Pramesywari.

An orangutan is released at Bukit Tiga Puluh National Park. Photo credit: Winny Pramesywari.

“I also face many sad times. I see how the forests change to plantations (mostly palm oil) or coal mines. The weather gets hotter and human-wildlife conflict increases. I can hear the sounds of chainsaws from my field-site, meaning the illegal logging is getting closer. In dry season, the sawdust flies and the smoke goes everywhere. Some parts of the forest are burned to make new plantations.

“We are finding animal tracks closer, surrounding the site, probably moving to a more secure area for them. The most heart-breaking moment is when I need to rescue or treat animals from human-wildlife conflict or illegal poaching. Some of them are even found dead! No matter what, wildlife always becomes the victim of human greed.

“Being the only vet, particularly as new veterinary graduate without a on-site senior vet and supervisor, was not easy and sometimes stressful. Having to work with a very basic medical facility also makes me think efficiently and effectively to utilize the limited resources.

“My knowledge never seems enough to face different cases each time. However, I have an opportunity once a year to meet other colleagues whom work on orangutan conservation through Orangutan Veterinary Conservation Group (OVAG) workshop. The event that is supported by Orangutan Conservation and Chester Zoo is a means of sharing experiences and gaining knowledge that really helps our work and improves the quality. It also makes our relationship closer, like one big family. It is much fun!

The happy faces of participants of OVAG Workshop 2013

“I now work at the SOCP quarantine centre – on the front line of orangutan rehabilitation. It is different from the release centre. This gives me a good picture of the problem for orangutan conservation. Every month we can receive one to two new orangutans. They come due to many reasons – as illegal pets, confiscated from poacher or illegal wildlife trader, rescued from conflicted area, or repatriation from another country. We are lucky enough if they come under good conditions. But sometimes they suffer serious injury or illness, some with very deep traumas.

“Recently, we have seen many new-arrivals which are babies. Their cuteness makes many people want them as a pet. But the tragic story behind this is if you see one baby orangutan in our centre (as a pet or being sold anywhere), it means at least one orangutan died. None of the mother’s give their baby up voluntarily and the poachers need to kill them to take the baby!

“Neither my friends or me can work alone to save them. We need your help! The easiest way is to stop keeping wildlife as a pet! You can also help by using only environmental-friendly products and use them wisely! [Learn more about palm oil here.]

“Together we can act better to save the wildlife.”

I am Winny Pramesywari and I Act for Wildlife!

After reading our previous blog you should have an idea of what OC/OVAG (Orangtuan Conservancy – Orangutan Veterinary Advisory Group) is and the main aim of the project.

As we mentioned, two vets from Indonesia – Winny and Siska – are currently on a three month placement here in the UK. They will be spending time here at Chester Zoo, meeting with different members of staff across the organisation to improve their skills and knowledge.

Through OC/OVAG Winny and Siska are able to improve on their skills in various aspects of wildlife and orangutan health which they can then take back with them and apply to their day to day jobs.

They will be keeping us updated on what they get up to during their time here, which we will obviously share with you too.

Siska has been working with the orangutans in Indonesia for around seven years, gaining most of her experience from working at a rescue and rehabilitation centre. The centre she is currently working at – based in central Kalimantan – is run by the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation (BOSF). The main aim of the centre is to rescue and rehabilitate displaced orangutans and prepare them for a healthy life back in the wild.

Siska exploring Islands at Chester Zoo, with OVAG mascot Gavo. Photo credit: Siska Sulistyo

When Siska first started working there, back in 2007, the centre held around 700 individual orangutans. Today they have around 491.

Here she tells us more about the work she does and her role at the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation:

“My day at the Nyaru Menteng center would start early morning, when I and the other vets make rounds and generally check the orangutans in the group that we supervise on that day. There are nursery group for orangutans aged under three years old, forest school group for orangutans between three to six years old, and the big ones are divided based on their location.

A group of orangutans at the ‘forest school’. Photo credit: Siska Sulistyo

“Routine activities include attending the patients, preparing and giving medication, discussing any husbandry issue with the keepers, doing lab work, and keeping records of everything that we do. As I was the head of the vet team, I also have to make sure that the clinic supplies, people’s schedules, and other administrative works are met.

“During my time at the center there are special cases and events that was close to my mind. In 2010, due to failed contraception program, one of our female sub adult orangutan had a baby, which was not expected at all. Adding to the problem, she refused the baby. As it was a few days old, it was decided that I would take care of him. Wigly, we named the baby later, was in a poor condition for didn’t get enough milk from his mother. I put him on tiny IV drip, and bottle-fed him every two hours. As I never had a baby of myself before, it was quite exhausting for me. Every night I had to take care of Wigly, and on day time I had to work as usual. Learning to be a mom is hard!

-with-ben-another-captive-born-at-1-year-of-agesmall.jpg)

Wigly at the rehabilitation centre with other juvenile orangutans. Photo credit: Photo credit: Siska Sulistyo

“Luckily my effort was succeeded. After two months, Wigly had grown into a healthy young infant. Today, Wigly is a big five-year-old boy and has a dominant personality among his mates at the forest school.

“At the moment, the number of orangutan population in Indonesia and Malaysia has declined almost 75% in less than 100 years. The threats are numerous, as it is with other endangered wildlife. Orangutans in Indonesia are especially threatened with habitat loss due to forest conversion into mining, monoculture plantation, and human settlement; poaching for illegal trading; as well as hunting for bushmeat.

“With the remaining population struggling in patches of forests in Kalimantan and Sumatra, a comprehensive strategy must be done to prevent the numbers from constantly decreasing, stop the habitat conversion and habitat destruction, and supplement the current population by reintroducing viable sub-populations. The last step is the main aim of BOSF’s orangutan rehabilitation centers. We rescue and confiscate displaced orangutans, treat them and rehabilitate their physical and behavioural aspects, and when they are ready, they will be brought to their new, and hopefully last, home in the primary forest in the heart of Borneo.

small.jpg)

small.jpg)

Siska with her team releasing rehabilitated orangutans. Photo credit: Siska Sulistyo

“Starting in 2012, BOSF has released a total of 167 orangutans into safe forests. As we have two centers in East and Central Kalimantan, we also have two release sites for each. We the vets are involved in the preparation for the release, escorting during transportation to the release site, and post-release monitoring on those we have released.

“Today, with my role as the coordinator for animal welfare, my responsibility extends not just on the animals at the center, but also to another center in East Kalimantan. In total, both centers under BOSF are taking care of 704 orangutans and 56 sun bears.

“My responsibility is not just on the veterinary side, but also on the general welfare aspects of our animals. That means I have to know everything from enclosure designs, enrichment, nutrition, up to the behavioral observations and analysis which is critical to determine if an orangutan is ready to be released or not.

“Since 2009 I was involved in a network called OVAG (Orangutan Veterinary Advisory Group). This started as a workshop initiated by Orangutan Conservancy, to build capacity and gather veterinarians working in orangutan conservation in its own habitat. Chester Zoo had been involved in the initiation and since then continuously supports the group with the scientific and skill resources they have. From OVAG I have gained so much, not just professional developments on veterinary and conservation management, but also family and friends.

“I am still learning a lot at the moment, and with the help and support of the amazing team of BOSF, families of OVAG, and other supporters, I hope to be able to keep contributing to the conservation of orangutans in Indonesia.”

Tomorrow we will share another blog with you, this time from Winny – who has provided us with an overview of the veterinary work she’s doing in Sumatra.