We talk to globally respected forest conservationist Dr Marc Ancrenaz, Co-director of the NGO Hutan, which has been pushing for a sustainable future for wildlife and people in Malaysian Borneo since 1998.

As world leaders discuss climate change and threats to wildlife over these long months ahead, no doubt you’ll hear the term “deforestation-free commodities” crop up. If you’ve been following Chester Zoo conservation work for a while you’ve probably heard of “sustainable palm oil”, too. These terms encompass some of the most enormous and challenging conservation issues around. “Commodities” and “palm oil” are also incredibly emotive terms, ones that conjure imagery of vast plantations stretching to the horizon, or of injured orangutans pictured amongst the surroundings of a felled landscape.

It’s so tempting to hope for a simple solution. Should we end consumption of the crops most associated with habitat destruction such as palm oil? End demand and see the return of forest?

Let’s cut through the noise and the shouting of debate, and take a look at what life is really like where palm oil, commodities and wildlife are not so distinct from one another after all.

Dr Marc Ancrenaz (pictured below) has been the Co-director of conservation NGO Hutan since 1998, when it first began vital work in Sabah, on Malaysian Borneo, taking action against the decline of some of the most thriving and species-rich habitat that the planet has to offer, through habitat protection, reforestation programmes, and carefully planned community outreach and engagement.

In a hurry?

Check out a quick summary or head down to full conversation below

- In Sabah, Borneo, former fishing communities have forged a new living after the river fish stocks can no longer support demand.

- Now small and large farm holders grow crops such as palm oil across vast areas – a complex scenario with benefits and negatives for wildlife.

- The land is a livelihood for countless people. Removing demand for certain crops by boycotting them only drives people into poverty and regresses the situation. We must work with land owners, both big and small, to make their landscape more resilient for nature.

- Sustainability certification schemes hold the answer for people across the world to unite in solving the issue, and empowering the consumer, but it can only succeed if it reaches a critical level of support.

The full conservation with Dr Marc Ancrenaz begins…

Marc, You’ve spent two and half decades living in one of the most wildlife rich areas of the world, what’s the situation like on the ground today…

Sabah, northern Borneo, my home, still has nearly 50% of its landmass covered with forest, and nearly 30% of the land mass is fully protected by State authorities. This sounds like a lot, and it is when you look at many other places in the world. However, the forest that has survived is not in areas that are commonly used for agriculture or other kinds of development, and is mostly located in the highlands.

In the lowlands, close to the coast, things are very different.

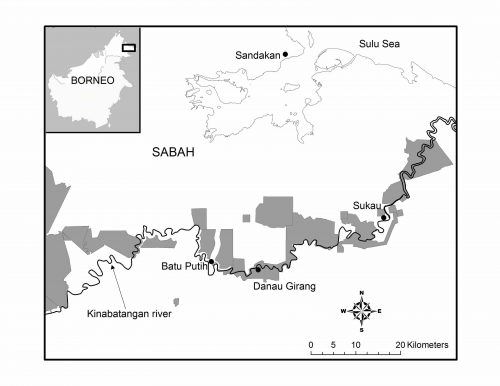

If we zoom in on the Kinabatangan area, where Hutan focuses its work, you have the large river, Kinabatangan, that flows all the way from the mountains to the Sulu Sea, and forms one of the last vital links between highlands and mangroves in Borneo. Along this river you have all kinds of ecosystems. There is half a million hectares of land here, but only about 10% of it remains as forest. The biggest agriculture type here is palm oil, which suits the region’s floodplains very well.

Image – Hutan’s conservation focus lies along the Kinabatangan river in Sabah, Borneo. Shaded grey areas on the map indicate protected areas.

Ironically, many large mammals including orang-utans, elephants and other species are preferentially found in the lowland areas, rather than the highland forests.

Go back in time 50 years and you’d be looking at a different world. In the 1970s, before mass logging started, this area was effectively pristine forest. Now 90% of it is gone, and what is left is degraded and fragmented.

Having said that, even today Kinabatangan remains a biodiversity hotspot for South East Asia, despite the stage of degradation and human-driven transformation. Even though the landscape is permanently changed by agriculture and other land uses, this area is still important to sustain wildlife – this is a no brainer – and we need to make these new landscapes more resilient for wildlife.

Image – The meeting of palm oil plantations and thin stretches of forest along the banks of the Kinabatangan.

Image – The meeting of palm oil plantations and thin stretches of forest along the banks of the Kinabatangan.

And what’s it like for communities living in the Kinabatangan area now?

The local communities here have faced tremendous challenges over the last 20 years especially. Most communities have their history tied to the river. They used to be communities of fishermen deriving their survival from the freshwater ecosystem. They did this for thousands of years, but in two decades everything has stopped. Pollution, low water quality, and overexploitation have depleted the main source of income for many – freshwater fish & prawns.

Image – An example of a human settlement on the Kinabatangan river

People are re-inventing themselves to survive. Today these communities are managing nearly 40% of Sabah’s agricultural land under palm oil plantations as “smallholders” – small plantations or orchards normally no more than 5 hectares in area. The rest is mostly owned by large corporations, plantations on which many people labour, some native from Sabah, others displaced from places where opportunity is even more scarce.

Image – A smallholder oil palm farmer handles a harvest

People living here can now feel the climate changing too, they can see it. In Borneo, during El Nino we are heavily affected by fire, and during the monsoon, deluged by flash floods. These events might not be more frequent than before, but the intensity of them has been increasing and people are suffering. They are realising the role that the forest played in mitigating extreme weather. I talk to people living near the river and they say the weather used to be more pleasant, less hot, with more regular rain. It was easier to live.

Image – The effects of a recently passed forest fire on the Bornean landscape

People are clearly struggling in these agricultural areas then, is this attitude to the challenge shared by people across Borneo?

No, in the cities, people don’t realise. I think this is a challenge around the world. I’ve met so many people living in Malaysian cities that tell me about how they’ve taken flights out of the cities and looked out of the window at the ground below, shocked at how the landscape has changed in living memory.

I understand though, it’s so difficult to imagine decline at such a scale. There is no real difference between what’s happening here now and what happened in the western world centuries ago. In the UK, in France, in America, there was once huge amounts of forest, but its removal has passed beyond living memory, and it’s hard to see the landscape for what it once was.

What we have to do here is make the best of what we’ve got, to make it clear what the path forward is for those people who don’t realise what impact the damage being done every day will have in the future.

Image – A portion of the Sabah landscape as seen from the window of a small aircraft

What is our way forward then? People are always going to need to survive on this land, but how can we reduce the pressure? Could a boycott be the way forward?

It’s a complex issue, and as for any complex problem there’s no easy answer. Fifteen years ago, as people were realising what was happening, calls for a boycott on commodities like palm oil had their place in starting the conversation, but that time has passed now and we need to act on today’s reality.

Let’s imagine a world where a full boycott begins tomorrow. The situation for orang-utans and for elephants would likely not be any better. First of all, the people would again lose a major source of income. If we allow people to fall further into poverty, all that will happen is the resumption of forest destruction as people do what they need to do to feed their families.

Secondly, if the palm oil industry stops tomorrow, all of the places that have been planted with palm oil will not suddenly go back to being forest. Instead people will use them for whatever crop will offer the next best income on the land – acacia, rubber, whatever works.

Image – Numerous crops are grown and sold within the Sabah landscape, not just oil palm

Thirdly, a boycott closes the door to any kind of discussion with a producer. Even if you ban production of a certain crop, the people that use this land for production aren’t going anywhere. The best chance we have when thinking about biodiversity is to engage with every landholder we can, to convince them to improve their practices and design more resilient landscapes.

We have a path forward to work with, we just need to engage… so how, and with who?

Smallholders cannot afford to halt production on much of their land to make a forest corridor, it would not be fair to hit their livelihood so heavily. Instead, we design our corridors at the landscape level. Imagine from above, like when you’re in a plane, how a network of small farms might look in the UK. Is every farmer growing the same crop? Of course not, and there are spaces between farms too. Small holders effectively create a mosaic of small pockets of different habitat throughout the landscape. In a way, the diversity of habitats is already offering a great way for wildlife to continue to exist.

Image – Dr Marc Ancrenaz leads a stakeholder discussion with smallholder farmers

When it comes to building corridors for large mammals to move through the landscape, we bring in whole communities of smallholders together to find compromise, and ensure nobody feels cheated or left behind.

But for us, a current ‘hanging fruit’ is with the largeholders. Most of the time there is no mosaic on these vast areas of land, just monoculture of palms aligned one row after the other. Here we can make the biggest difference.

If the answer is with those who own the most land, how do we engage with them then? What’s the realistic solution?

When we look at all these complex issues the future can seem bleak. However solutions do exist. one for example could be a more efficient certification of commodities. Standards like the Round Table on Sustainable Palm Oil.

In the past, commodity producers and NGOs didn’t talk with one another, but this is changing. Land holders these days are more receptive than ever to how they are perceived, and how national and international criticism or campaigns might affect their business.

Certification standards are promoting better practices. They offer a clear message of the way forward for everyone: producers, consumers, NGOs, governments.

Of course, I know that certification is far from being perfect yet, I do, but we can make it work by uniting on all sides. A certification scheme is only as powerful as the number of people that have confidence in it. The more people that support it, the stronger the case to join the programme, and the stronger the case to make sure it is carefully regulated, and that cheats are caught and punished.

For us at Hutan the vision is simple, we need to retain or recreate as much natural space as possible to sustain large mammals and a countless number of other species. Elephants or orang-utans need vast spaces for their movements and to maintain viable populations. Although they are extensively using the current protected area network, these forests – mostly among the highlands – are disconnected and are not sufficient for a roaming needs of such animals. Elephants also need resources located in these farmed lowland areas too. They are always going to need to move throughout the entire landscape.

We could close our eyes, slam the door shut on industry by demanding a boycott. We could choose to focus exclusively on protected areas. But… this would only aggravate the situation and harm the chances to sustain these species in the long-term. Connectivity of the whole landscape is needed, and thus we need to consider agricultural landscapes within our conservation strategies.

Image – A member of the Hutan reforestation team heads towards a small palm oil plantation on which the tree saplings she is carrying will be planted, alongside many others, to improve the connectivity of the landscape.

The only way forward is to work with land holders, large and small, to make this landscape the very best it can be, for more people and wildlife.

You, the reader, have immense power as a consumer.

Get in touch with your elected officials, tell them you feel passionately about this, tell them to push to strengthen certification schemes on the world stage. Making choices in the supermarket can be difficult, but if governments decide that nationally, importing exclusively sustainable certified commodities is a necessity, then that choice is made easy.

The stronger we make certification schemes, the better things become for the wildlife and people of Sabah, and in other places around the world too.

Image – A young Bornean orang-utan looks down from the forest canopy.

Our Position

Chester Zoo is a long-time supporter of certification schemes, which can be part of the solution in achieving deforestation-free commodities. We’re invested in helping to improve these schemes, pushing schemes towards stronger criteria and improved transparency. Like our close friends & partners at Hutan, we see the potential for a sustainable future for commodity production around the world, but only will this be possible if consumers, producers, supply chains and governments unite to make it happen.

Read about…