The latest in our studentship series comes from Tom Lewis who studied the Sao Tome fiscal shrike, a bird endemic to the island of Sao Tome in the Gulf of Guinea. This bird supposedly disappeared for around 90 years before being rediscovered in 1991. Read all about Tom’s research and how Chester Zoo’s support made his project possible:

“We were woken up by the trucks carrying the oil palm plantation workers to work. They started arriving about 4am, whilst it was still dark! Some of the trucks have come over 30km to get here, so they must have left early.

“As the sun began to rise around 5:30am, we got up and prepared ourselves for the day ahead. When I say prepared, I had no idea what I was going to be doing. I knew the plan; we were hiking into an area way into the forest that had been recommended to us as a study site. I didn’t know how far it would be or how hard the hiking would be. I was going to be hiking into the unknown.

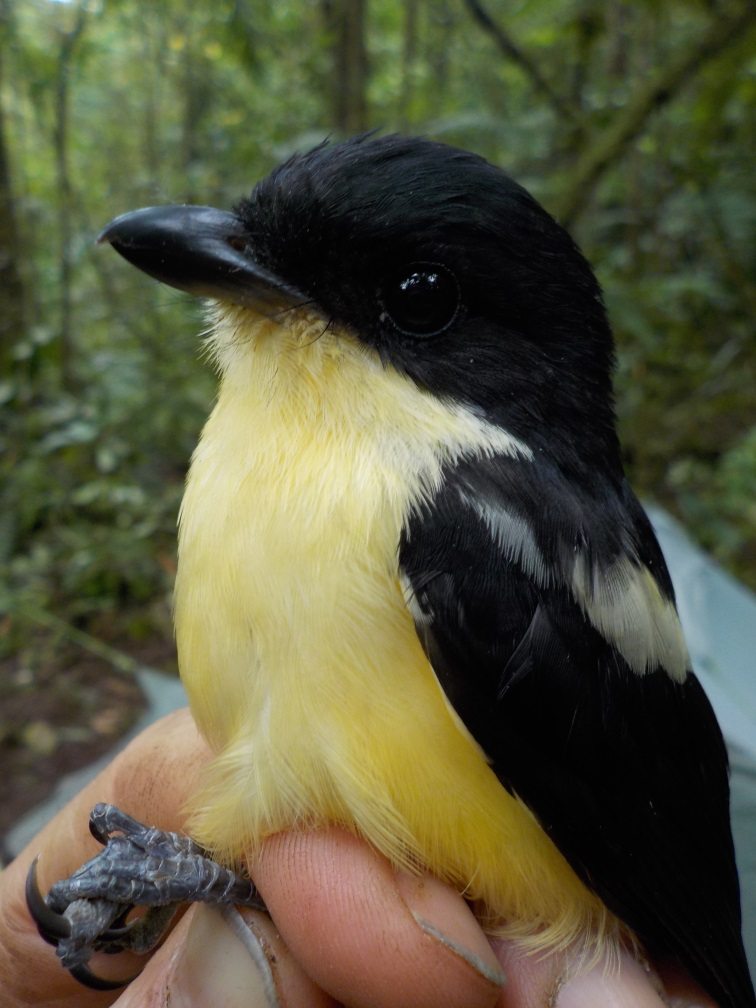

“I was searching for the elusive Sao Tome fiscal shrike (Lanius newtoni), a bird that had been rediscovered in 1991 after 90 years of apparent absence. Since then birders had reported seeing it in various places in this small, forest covered island; mostly in the places where people don’t usually go, across the rugged south west or along ravines in the central massif.

“The Sao Tome fiscal shrike is classified as critically endangered by the ICUN but apart from a BirdLife International action plan, very little research has been done on this enigmatic species.

“The hike into the forest was long and unbelievably tough; the forest we were hiking into was an extremely rugged region, characterised by narrow volcanic ridges and steep ravines. But before we reached the forest we had to hike for about an hour to get out of the oil palm plantation. This plantation hadn’t been here five years ago, the forest it replaced had been prime habitat for another critically endangered endemic bird called the dwarf olive ibis (Bostrychia bocagei). It was sad to see that such a small island seemingly too small to make oil palm viable, had been blighted with the same scourge as large swathes of South East Asia.

“On the hike we didn’t see or hear any shrikes so when we finally reached our first camp I was relieved to hear a distinct whistle in the distance. Its call is a repeated short whistle, occasionally another bird will reply – maybe it’s a territorial call or maybe a contact call with a mate? The studentship from Chester Zoo along with funding from BirdLife International and Nottingham Trent University helped me fund this research project.

“The Chester Zoo studentship went towards paying for my guide Mito, an incredibly knowledgeable guy. Without him my research would not have been possible. My work was focused on the habitat associations of the shrike to try and give a better idea of areas that might be under threat and identify if any immediate conservation actions are required.

-tom-and-martim-(student)-in-forest-small.jpg)

Mito (left) my guide, me (centre) and Martim (right) a student, sat in on of our final camp in the forest

“In certain areas of the study site shrikes were extremely numerous, at one camp site we must have been in the centre of a territory as every morning at first light we were woken with whistles just above our heads. Apart from birders who come to tick the shrike off their list only a few people have actually spent any time in the forest studying the birds so I felt extremely honoured.

“Overall the study was successful; we even came across a few juveniles at various stages from recently fledged to almost full adult plumage, something that even fewer people have witnessed and adds to our understanding of the shrikes breeding biology. The location of shrike populations seems to be associated with higher elevations, and open midstorey; it wasn’t in the scope of my project to investigate the reasons but this is mostly likely due to its prey and hunting technique.”