Tag: Living alongside wildlife

Researchers on the island of Java have discovered populations of an almost extinct species that is regarded as the “world’s ugliest pig”. The population of the Javan warty pig, listed as endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), is estimated to have decreased by as much as 50% since 1982.

It was even feared that many, if not all, populations of the Javan warty pig had become extinct until their existence was confirmed by our camera traps. The plight of the animals reveals the cost of hunting and the destruction of forest habitat in Indonesia.

The scientific research we’re supporting, is working to understand the little known animals and any steps that need to be taken in their long-term conservation. It could eventually be used to establish new protection laws for the species as currently they’re not protected by Indonesian law.

Dr Johanna Rode-Margono, South East Asia Field Programme Coordinator at Chester Zoo, designed the study to try and locate the last Javan warty pigs alongside Indonesian researcher and Project Manager Shafia Zahra. Johanna tells us more below:

“Javan warty pigs are of a similar body size to European wild boar but are a bit more slender and have longer heads. Males have three pairs of enormous warts on their faces. It is these characteristics that have led to them being affectionately labelled as ‘the world’s ugliest pig’ but, certainly to us and our researchers, they are rather beautiful and impressive.

Indeed the Javan warty pig is a special animal. They are unique and can only be found in Java. Little is known about them and that very fact means we need to preserve them. We just don’t know what havoc it could wreak for other wildlife if they go extinct.

Watch the below interview with Shafia, which also includes some of the first ever wild footage our cameras captured of the Javan warty pig, to discover more about the research she’s been carrying out in Java below:

Out of the seven locations surveyed by Shafia, across Java between June 2016 and May 2017, only four sites were found to have pig present, meaning that the species is highly likely to be extinct in the other three.

The second phase of the project is now underway to try and estimate the exact population size of the Javan warty pig and assess the impact that hunting is having on the species.

Following on from her previous blog, ‘People, tigers and leopards‘, Amy tells us more about what it’s like being in the field and some of the challenges she faces when working on the Living with Tigers project.

“You might think that as zoologists or conservation biologists we know and recognise all the species in an area that we work in, and to a point, we do try very hard to as a habitat’s species richness is one indicator of ecosystem health. However, the difficulty in identifying species appears when you have images on your camera trap that are blurred and dark.

“It sounds simple to identify a specific species from a picture theoretically, so why is it so hard to actually identify one from a camera trap image?

“There are many reasons explaining why identifying animals from camera trap images is difficult but one that I wanted to highlight is the variation within a same species across different countries. Having one species with different looks can make it really confusing to identify it and can easily make it look similar to other species present in the area.

“For example, the leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) in Nepal looks different from the leopard cat in Borneo. Above you can see that the tail of the leopard cat in Nepal is longer and much fluffier, with more stripes than the individuals in Borneo (below) and can be easily confused with a marbled cat (Pardofelis marmorata) if the photograph is not clear. Also from the markings on the front of the neck and the spots on the body, it can be confused with the fishing cat (Prionailurus viverrinus), although for some locations this would be a rare find and a new record for Nepal.

“Another good example of how tricky identification from camera trap images can be is the common leopard (Panthera pardus). There are many subspecies of the common leopard, but the one I want to highlight is the Indian sub-continent subspecies (Panthera pardus fusca).

“In India, leopards look pale to golden in colour but in Nepal, the Living with Tigers team captured on camera a male and a female leopard that were particularly orange. This observation sparked the question as to whether all Nepalese leopards are more orange than the same subspecies that occurs in India or whether it was just an individual characteristic of those specific individuals.

“It is always important when starting out as a young conservationist to follow your instincts while respecting the knowledge of others. What do I mean by this? Well, the beauty of camera trapping is that you might capture species that are rarely seen or record a species in a location for the first time. The latter means that experts might tell you that you could be wrong because a particular species is not recorded for your location and the image may not be clear enough for a positive identification. Don’t let that stop you making sure you have the correct identification for each species!

“I conducted some camera trapping in Borneo in 2014 and found some images of a pheasant species on my camera traps. Even though birds were not the focus of my study, I wanted to know what species it was, so I asked a bird expert for his opinion. He said that it looked very much like a rare species of pheasant (Bulwers pheasant) which had never been recorded in that location. Looking at the images that my camera traps had recorded, he confirmed that I had captured images of this rare endangered pheasant, making it a new record for the species in that region! So, if ever in doubt the best thing to do is to double check and double check again.

“One of the exciting things about being a conservation biologist for me is definitely the mysteries. Why do leopard cats in Nepal have fluffier and longer tails than those in Borneo? Are all Nepalese leopards more orange in colour compared to the ones in India or could it just be a few individuals of that subspecies across all its range that share that specific colour? That’s what science is all about, stumbling onto mysteries and collecting data to resolve them!”

Amy was recently interviewed on Bristol Community Radio bcfm for a programme called Shepherds Way. You can listen to it here by selecting the 27/09/2017 programme to learn more about the Living with Tigers Project and Amy’s work.

Last year’s pine marten translocation efforts started in early September in Scotland. This time is best for getting the martens as it’s outside the period where females have dependent young, and after the mating season that happens from July to August.

A total of 19 adults, including ten males and nine females, were carefully health checked and selected for translocation to Wales. After being fitted with GPS collars, the pine martens travelled to their allocated release site in Wales. The soft-release pens that we designed and built were used to help the martens acclimatise to their new surroundings, and most of the animals went on to establish stable home ranges and remained within 10km of the release sites.

Sarah Bird, Chester Zoo’s Biodiversity Officer, explains:

“I am really pleased with the continued success of the Pine Marten Recovery Project, and proud that Chester Zoo’s involvement is growing. It’s superb that zoo staff are able to help with radio tracking and develop their skills on this exciting UK native species project. The steps The Vincent Wildlife Trust are taking to monitor local views and engage local communities are extremely important too, and I hope Chester Zoo will be able to assist in this area in the future.”

Radio tracking the individual martens to establish their home range was an important part of the project, and the radio tracking effort was intensified this spring to try to determine if any of the translocated martens (from 2015 or 2016 releases) showed signs of breeding. Breeding female martens tend to spend more time close to their den site and that behaviour can be easily picked up by radio tracking.

Dens identified as likely to be used as natal dens were checked in May and camera traps were set up around the potential sites. The Vincent Wildlife Trust identified that at least five females had successfully bred resulting in the birth of 10 Welsh-born pine marten kits in 2017. One family resulted from a mating in Wales last summer between martens released in 2015, indicating that the pine martens are settling well in their new home in Wales!

A third and final translocation is now under way to release a further 10 to 20 Scottish martens in mid-Wales. This last translocation will strengthen the founder population even further and should enable a faster spread of the newly established martens.

Another important measure of the future success of the Pine Marten Recovery Project relies heavily on the involvement of the local Welsh communities. Josie Bridges, Pine Marten Project Officer and specialist in Community Engagement is in charge of that aspect of the project. Training volunteers, Josie enables local people to become Pine Marten Champions.

She tells us:

“Fostering community ownership is such an important part of what we do in the Pine Marten Recovery Project. These pine martens are part of the Welsh community now and we want local people to be aware of them, help us monitor them, and benefit from their existence here.”

A camera trap loan scheme launched last year has proved very efficient in building the bridge between locals and pine martens. The scheme allows local people to put a camera trap in their garden or field, and helps the project keep up with the movements of the pine martens, whilst getting people curious about their new elusive neighbours. Some community groups have become so involved in the project that they organised a ‘name the pine marten’ competition where a marten is regularly seen!

Josie adds:

“We want to improve and expand on the communities initial excitement at the translocation so that in 5, 10 or even 50 years’ time there will still be pine marten champions in the area to show how the pine martens have survived and thrived back in the Welsh landscape.”

We’ve been working with partners in Assam, India for over a decade supporting local communities that are affected by human-wildlife conflict. Elephants are in competition with people for space and as they move between small patches of remaining habitat in the search for food and water they come in to conflict with people.

During the expedition to Assam two years ago, the team ran a series of workshops that focused on ways to improve livelihoods. Building up this sustainability will in turn build up the villager’s capacity to deal with the elephants they share this landscape with and reduce human-elephant conflict.

Chester Zoo’s lead horticulturist, Maile Belanger, was one of the team members who went on the zoo expedition two years ago. She was recently invited back to carry out more workshops with local villages. Below she tells us more:

“I had the great privilege of going back to Assam, India to assist in the work that the zoo’s Assam Haathi Project does in bettering the lives of people that suffer from human-elephant conflict.

“In February 2015 I was part of the Chester Zoo Expedition team that went to Assam to run a series of workshops with the aim of developing skills for alternative livelihoods. My role on the expedition was to prepare and present horticulture workshops. And on the back of good feedback from the trip I was asked to go again and visit new villages and repeat the same workshops.

“My first presentation focused on soil (soil texture, pH, soil nutrients, compost making, green manure) and the second focused on pest and disease prevention (type of pests, homemade/organic pesticides, diseases, avoiding diseases, homemade/organic fungicides, companion planting, crop rotation). For my latest trip, I was asked to prepare a presentation on oyster mushroom growing. Well, this was completely new to me so in addition to doing some research on the internet I also bought myself a mushroom growing kit. I was also successful in growing some mushrooms before I left so I felt confident passing on my knowledge.

“In 2015 we visited villages where their main crop was rice and growing vegetables was just a side-line for some; but this trip would involve visiting villages where vegetable growing was their main income. The range of vegetable was wide and all familiar to me as I am a keen vegetable grower with my own allotments. This time of year the following crops were being harvested: okra, beans, aubergine, chillies, squashes, and cucumbers. The fields were being prepared for the planting of cabbages, cauliflower, potatoes, onions, garlic and greens.

“I was asked to prepare a fourth presentation focusing on some of the specifics of Vegetable Cultivation. This presentation focused on seed propagation, water saving watering techniques, and some extra tips on how to deal with common pets organically. The plan was to run four workshops, each workshop lasting two days in three areas of Assam, Biswanath, Sonitpur and Chirang.

“Unfortunately Assam was experiencing an extra warm autumn and the temperatures were around 35C each day. Another difference from last time I visited was how green everything was with the rice fields full of crop and leaves on trees.

I spent the first few days in Biswanath. This is one of the large tea growing areas and there was mile after mile of tea estates. The Assam tea plant is grown in lowland areas and amongst trees and is different from the Chinese tea plant that most people are familiar with. Most houses had tea plants instead of lawns around their houses. The tea picked (all by hand even in the large estates) was usually sold to the large tea estates to be processed.

“The next area we visited was an area we went to in 2015, Sonitpur. To reach the villages for Workshop 2 we had to take a boat and then walk about five minutes. This was a rather small boat around the size of a Canadian canoe and there were eight people, four bikes and all our workshop equipment combined with a fast flowing river…exciting! Just a few nights before we arrived a herd of elephants came through the area and caused crop damage and destroyed seven houses. Luckily no one was hurt.

“I just can’t image how scary that night must have been for the villagers. We were taken around the village to be shown the damage and also an electric fence that one family had tried to set up. Unfortunately the electric fence was set up incorrectly and was not working.

“The villages are in one of the main elephant corridors that runs from the Nameri National Park to the Jia- Bhoroli river and the rice fields across the river. There is no electricity in the villages so the elephants aren’t wary of going through. We crossed one of the smaller rivers by foot surrounding the villages to be shown the elephants. They usually forage in the forest during the day and come down to the river in the late afternoon for a drink. They then sometimes cross the river and go through the village to cross yet another river to continue to look for food. The elephants were about 0.5km away and only just grey blobs in my photos but nice for me to see. The AHP staff have said that they will give the villages some spot lights to help protect them in the future.

“While in this area we visited one of the villages I went to in 2015 to see one of the success stories from the workshops. One of the families are now able to grow chillies for the first time due to using one of the organic pesticide from the ‘pest and disease’ workshop. Before they were unable to grow the chillies because catepillars would eat the plants but now they don’t have that problem after using an onion and garlic spray. One of the chilli varieties they are able to grow is the Bhut jolokia or ghost chilli (some seedlings have been supplied by the AHP project) which fetch a good market price and are used in deterring the elephants.

“The next area to visit was near Bongaigon, Chirang and the site of the first electric fence that was constructed by the AHP. This area is vulnerable because the villages are on the edge of the Manas National Park and the Bhutan boarder where the elephants are protected. The electric fence has vastly reduced the number of human-elephant conflicts and the villages have been able to grow vegetables again and make a living. A trial lemon bush living fence has been planted in the area with the hope that the elephants won’t like to go through a thorny natural barrier and that the villages will be able to harvest and sell the lemons. At the moment the fence contains seven rows of lemon bushes and is 25 meters long. The lemons have grown well and there are plans on extending the fence for a further 1km along the Manas National Park boarder.

“Overall I believe most of the information I presented was familiar to the attendees or they were doing the practices but maybe didn’t fully understand the benefits, just following tradition. The vegetable plots I did see seemed to be very productive. There was definitely a desire to learn more about organic methods of growing especially for larger scale vegetable production. All attendees were very welcoming, attentive, took notes and were not afraid to ask questions. All attendees received a translated version of my presentation notes and will receive a certificate of attendance.

“I feel very honoured to have been able to present my workshops to all the areas that we went to and hope I have helped in some way. If I haven’t helped in improving the growing of vegetables I hope I have at least helped in forming a good impression of the AHP and cemented a great working relationship between myself and the AHP staff. I hope the staff feel they can contact me whenever and ask any questions as I want to help as much as I can even from a distance. I know I have at least encouraged the AHP staff to give mushroom growing a go.”

Studying forestry at Tribhuwan University in Nepal, Tilak Chaudhary then graduated with a Master’s in Forest Science and Forest Ecology at the University of Göttingen, Germany. He worked with a non-governmental organisation for two years before starting his master degree and then worked on a USAID funded project for ten months after graduating. His main interests lie in the fields of conservation, forest and biodiversity management, and local communities’ involvement and livelihoods.

Meet Tilak…

“In the past, national parks and wildlife conservation areas were established to keep local communities away. Nowadays, the scenario has changed and conservationists have started realising that conservation is not possible if local people are not included. For a protected area to be successful, it is crucial to work with local communities.

“By working with local communities, I came to realise that conservation is not only about the protection of a species, it’s much broader than that.

“Working as the LWT Project Manager allows me to be directly involved in conservation! I am mostly in charge of planning field interventions to mitigate human-tiger interactions, coordinating with conservation partners, doing field visits to ensure that the project interventions are effective and developed in the way they were envisioned, and meeting with local partners. On a typical day, I usually communicate with field staff for updates, but also explore ideas for potential interventions and prepare for upcoming events such as camera trapping activities.

The LWT project is developing interventions to mitigate negative interactions between humans and tigers, promoting alternative livelihoods and doing social marketing to change behaviours of local communities to minimise human-wildlife conflicts.

“These are important aspects that must be considered as Nepal has committed to double its tiger population by 2022. While promoting tiger conservation, the project is also promoting tourism in national parks using tigers as a flagship animal in both national parks. The project has also broadened the scope and recognition of Green Governance Nepal (GGN).”

Our Living with Tigers project in Nepal has been working on livelihood and conservation interventions by supporting the construction of predator-proof pens and biogas plants in various local communities. These interventions are benefiting both the local villagers as well as the biodiversity in Chitwan and Bardia, the two national parks the conservation project focuses on.

Recently, some Nepalese newspapers and online platforms took an interest in the project and a number of articles have been published nationally praising the positive changes that local people experience thanks to the project.

Prakash Chapagain, a Living with Tigers Field Officer based in Chitwan National Park, tells us more:

“The articles have outlined the activities conducted in the different sites of the project and also highlighted the perceptions that local communities and stakeholders have in regard to the project. These articles were published on Kantipur National Daily, Loktantra Sandesh National Daily, Tahakhabar and Setopati Online. The articles reflected the positive impact that the predator-proof pens and biogas plants have brought to local communities in the village of Madi.

“Ishwori Bote, a 48-year-old resident of Tamta-anar Ganeshkunja village explained that he lost several of his goats in the past to leopards that managed to get inside his old pen. However, he added that he is now confident that the new predator-proof pen provided by the Living with Tigers project would keep his goats safe! He said: ‘I am happy and confident that tigers or leopards cannot take my goats away anymore’. And he has also increased the size of his herd thanks to the project.

“Srimaya Bote, a woman from a marginalized group in Chitwan added that thanks to the support of the LwT project, she has been able to build a biogas plant in her community. Srimaya has since been able to enrol her children in school and doesn’t need to collect wood from the forest anymore thanks to the biogas plant installation. She explains:

My family is now safe from wild animals and we do not need to go to the forest in search of fuel wood anymore which means we have no chance of interacting with tigers and leopards.

“Ram Chandra Kandel, Chief Conservation Officer of Chitwan National Park stated: ‘These types of interventions are crucial for human wildlife conflict mitigation and are always carried out with a strong coordination from the Park Office’.

“Another news article highlighted how the installation of biogas plants has transformed the lives of locals in Bardia. Local villager, Hari Bahadur Buda explained that he had not needed to collect wood from the forest for more than six months now and added that he also felt much safer than before. Ramesh Thapa, Conservation Officer of Bardia National Park said: ‘Biogas has brought the illegal collection of fuel wood within the national park to an end.’

“These are only a few examples of how the project has already managed to impact the lives of many local communities in Nepal but many more are expected to benefit from the project in the future.”

Amy Fitzmaurice ran a workshop at the recent Conservation Optimism Summit to discuss human-felid conflict and its potential solutions with the participants. Below she shares what she covered in the workshop; an overview of the research she’s been carrying out to help protect people and tigers from conflict.

“The workshop called Tigers, Tigers, everywhere! What to consider when tigers are doing so well in Nepal? started by defining the meaning of human-felid conflicts. The term could be defined as ‘an incident between humans and felids in any environment that may or may not lead to injuries or fatalities of humans, human’s livestock or wild animals, like tigers and leopards.’

“However, in order to understand what the conflict means to different people I had asked beforehand people from around the world the following question: ‘How would you solve human-tiger conflict in Nepal?’

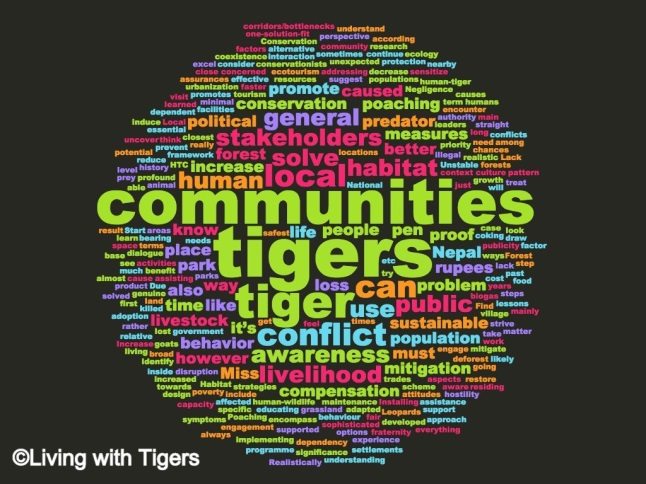

“We asked conservationists, social scientists, wildlife trackers, livestock farmers and many others. The word cloud below shows that, for many people, the word ‘communities’ was very much seen as a key aspect to solve this problem.”

“Word clouds were obtained by collecting all the answers to the question ‘How would you solve human-tiger conflict in Nepal?’ and by then putting them in a program able to turn them into a word cloud image. I think it’s an easy way to illustrate things when you’re talking to an audience that might not necessarily understand all the concepts that you’re talking about.

“All the quotes I collected during my research were used in discussion groups at the Summit to try creating solutions to human-felid conflict. These conflicts relate mainly to tigers and leopards killing livestock but can also include human-felid incidences, which can sadly lead to injuries or fatalities.

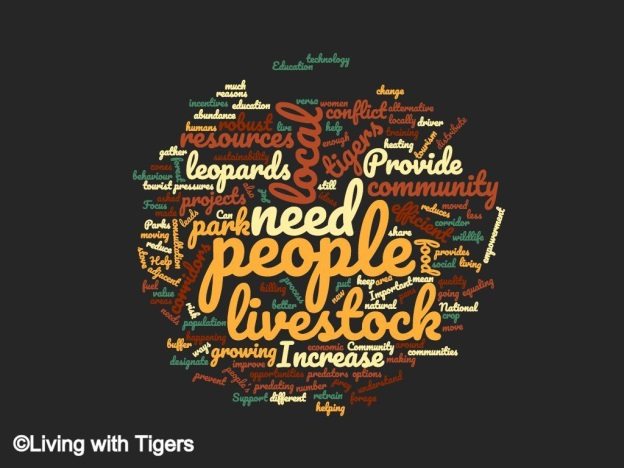

“A second word cloud was then created following the workshop and the word ‘people’ was at the centre of what participants thought was crucial to develop solutions.

“It’s interesting to see that generally the words ‘community’ and ‘people’ came out quite a lot! This is important because even though we are talking about tiger conservation, it can’t be achieved without further support of local people. Obviously having large carnivores can cause conflict with local people so it’s important that we always work with them to try and make sure that the local communities have what they need in life but also that we can help protect their local biodiversity.”

Some of the ideas that came out of the workshop to help solve human-felid conflict included:

- Increasing tourist value

- Understanding local people’s needs

- Focusing on corridors between the National Parks

- Increasing the abundance of prey to reduce risk of predating on livestock

- Increasing area for wildlife

- Providing alternative ways to gather resources

- Providing move efficient stove technology to prevent the need for so much fuel wood

- Support community driver incentives to change behaviour that leads to conflict

- Developing more efficient crop growing to reduce the need to forage

- Empowering women to help with population pressures

- Providing community training opportunities

- Consulting with local communities to get their ideas

“We as wildlife conservationists need to communicate and work with local people at the start of any project to understand their perspectives, needs and tolerances towards wildlife and help them solve their human-wildlife conflicts together.”

Read more from Amy and her work with the Living with Tigers project, here.

Following on from our previous blog: ‘Living with Tigers: it’s all about people‘, Chester Zoo Conservation Scholar, Amy Fitzmaurice provides us with another update from the project and the results from the household surveys the team carried out to understand more about the attitudes of local people and their perceptions towards tigers and leopards.

“As part of the Living with Tigers (LWT) project, Green Governance Nepal are assisting us in conducting social research involving both focus groups and household surveys, thanks to Darwin Initiative funding.

“The project team conducted almost 900 household surveys during 2016 across Bardia and Chitwan, two Nepali National Parks, to establish baseline attitudes and perceptions of local people towards felids. When asked if they agreed with the fact that leopards and tigers should be protected, a staggering 80% of local community members agreed that they should be.

“This positive attitude towards protecting tigers and leopards is a good thing for the LWT project team who is working with local communities to assess mitigation techniques, such as predator proof pens and biogas plants, being put in place to reduce human-felid conflicts.

“Mitigating conflict is one thing but understanding the ecology and behaviour of the emblematic big cats is also essential to insure that these techniques are actually efficient. Recently back from Nepal, the LWT team spent three months in the field assessing how tigers and leopards use the landscape around them, made up mostly of national parks, community buffer zones and villages. To get a clearer idea of the distribution of the two species, we set up camera traps and conducted transect surveys recording tiger and leopard tracks and collecting their scats for genetics analysis.

“The camera trap images we obtained showed that both tigers and leopards actually live alongside the local marginalised communities.

Camera trap images. Photo credit: Living With Tigers

“So how does this information on tigers and leopards help communities with human-felid conflicts? By studying the species’ habitat use patterns, we can identify areas of community buffer zones presenting lower risk of wildlife encounters. Our camera traps do not just capture tigers and leopards, but also other species such as elephants, honey badgers and many more, providing local communities with knowledge of the areas to avoid in order to reduce the risk of human-wildlife conflicts. This mapping process is called conflict hot mapping and will have to be monitored on a long-term scale to take into account the spatial movements of the two big cat species.”

The lovely people at Hannah Turner Ltd have created a very special product to raise much-needed funds for our Living with Tigers project. £1 from the sale of each of these handmade ceramic tiger money boxes will go straight towards the project, allowing us to continue our work with local communities to protect this iconic species.

In the last 20 years the population in the Terai, Nepal, has increased by 81% to over seven million people. This has led to habitat loss and fragmentation, but despite this the area is viewed as one of the worlds’ best remaining tiger habitats. Chitwan National Park and Bardia National Park are home to Nepal’s two largest tiger populations – it is estimated that there are around 120 in Chitwan and 50 in Bardia.

We’re working with the communities affected by tiger presence; the villages located around the edges of these two National Parks. The livelihoods of these villagers are closely linked to forests with the majority depending on its natural resources for income. People have to enter the forests to collect resources or graze their livestock and by doing so are at risk from tiger attacks.

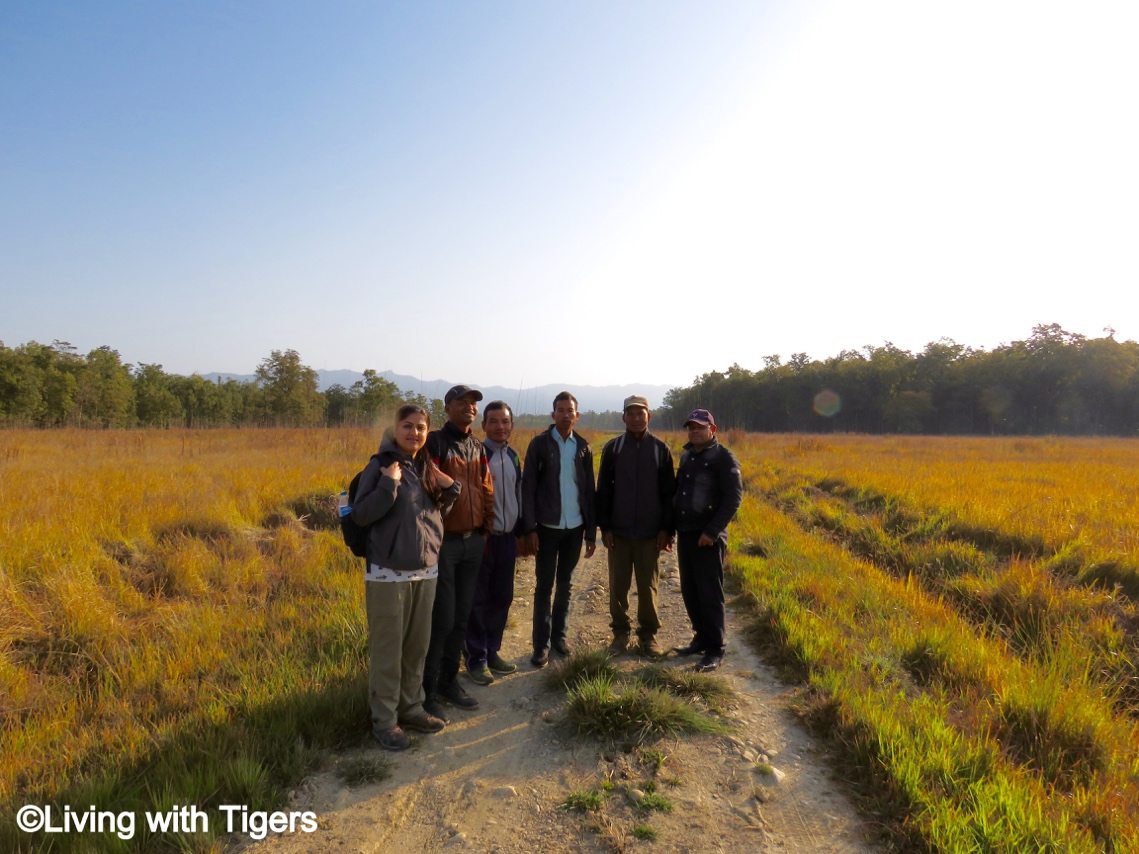

Last year the Chester Zoo team went to Nepal to meet our local partner, Green Governance Nepal, and the field teams working in Chitwan and Bardia National Parks; the two study areas for the Living with Tigers project. During this visit the activities included inaugurating the Bardia Field Office, conducting community focus groups on sustainable livelihoods, assessing the skills training local communities needed and meeting our other project partners: the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, the National Trust for Nature Conservation and the Swarnim Academy of Community Development.

Throughout August and September last year, the Bardia and Chitwan field teams successfully conducted the sociological side of our research; with a total of 882 questionnaires filled by local households. These questionnaires were designed to help us understand the impact that tiger and leopard conflict has on local communities living in our study areas.

In October 2016, the Living with Tigers team started implementing some mitigation interventions to reduce specific conflicts. The interventions were developed in partnership with the communities to make sure they were tailored to the specific needs of each of them. For example, predator-proof pens were built for households that own goats (and/or sheep) and requested this type of intervention.

During our visit, one villager told us that he had lost two of his goats recently, killed by a leopard only two weeks before we came! While there, the team helped build some predator-proof pens and had the privilege of being honoured by the community.

Another important component of the project is to facilitate lasting adoption of new behaviours, using social marketing, to bring about positive change in the local communities we work with. Working with social marketing expert, Dr Diogo Verissimo, we organised a workshop for the Living with Tigers team focusing on how to use social marketing techniques to identify current behaviours most pertinent to human wildlife conflict. The questionnaires completed last year by local communities will help us get a better idea of the factors driving their natural resource use behaviours and will highlight which behaviours are putting these local villagers most at risk of human-felid conflict.

The project is funded by the Darwin Initiative and in partnership with the University of Oxford’s famous Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU).

Keep an eye on our blog for more updates from the Living with Tigers team.

Studying conservation biology at the University of the West of England in Bristol, Amy Fitzmaurice then graduated from a Masters in conservation science at Imperial College London. Amy is now one of our DPhil (PhD) researchers from the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit at Oxford University and is currently assessing the interventions put in place in Nepal to reduce human-wildlife conflict with the aim to help tigers, leopards and people. She tells us a bit more about her background and the project, below:

Meet Amy…

“For my Masters, I went to the SAFE Project in Malaysian Borneo, a project where researchers monitor the impact of land conversion from rainforest to palm oil plantations. I conducted baseline social surveys of surrounding communities and logging/palm oil company workers to understand their level of knowledge about wildlife and investigate illegal wildlife trade issues.

“As part of my PhD, I will be working with the Living with Tigers’ team. We are working with local organisations and communities to implement conflict reduction interventions. My project is assessing whether these interventions are successful at reducing human-wildlife conflict. I always wanted to be involved in tiger conservation and the Living with Tigers project is particularly significant because it focuses on the human-felid conflict that is an important current conservation issue.

“As part of this project I will be studying the Bengal tiger and the leopard. Conflicts between humans and wildlife can arise for many reasons and it can often depend on human point of views.

In Nepal, the two main conflicts are leopards predating livestock in communities and humans encountering tigers inside the national park, which can sometimes lead to human injury or death.

“The research looks at both the ecological and sociological sides of the issue. The ecological aspect consists of using camera traps to survey both Bardia and Chitwan National Park’s biodiversity while also collecting signs of animals, such as scats and tracks. The sociological research involves conducting focus groups and semi-structured questionnaire surveys with communities surrounding both National Parks to collect data on the impacts felids have on their lives and will be carried out by Green Governance Nepal, our Nepalese project partners.”

Keep an eye on our blog for more updates from the Living with Tigers project.