Tag: Animal health and wellbeing

We follow Indali’s journey on the road to recovery, after being diagnosed with early stages of EEHV (Elephant Endotheliotropic Herpesvirus).

Three-year-old Nandita Hi Way and 18-month-old Aayu Hi Way – two much loved members of the zoo’s close-knit family herd of rare Asian elephants – both tested positive for the fast acting Elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus (EEHV) on Monday 22 October.

EEHV is known to be present in almost all Asian elephants, both in the wild and in zoos across the globe, but only develops into an illness in some elephants and when it does it is almost always fatal.

Dedicated elephant keepers at the zoo detected signs of the virus in Aayu and Nandita early and, utilising state-of-the-art technology in the zoo’s on-site science lab, were able to confirm the presence of EEHV at the earliest possible moment and immediately begin treatment.

A team of expert scientists, conservationists, keepers and vets are working around-the-clock to administer anti-viral drugs to help the young elephants to fight the illness. The team have also performed ground-breaking elephant blood transfusion procedures to help their immune systems fight back.

Mike Jordan, the zoo’s Director of Animals, said:

EEHV is an incredibly complex disease. It affects the membranes in elephants, so it occurs in their saliva in their mouth, in their trunk and in their gut. The virus attacks those membranes and causes a haemorrhagic fever and intense bleeding very, very rapidly.

Aayu and his half-sister Nandita are wonderful, charismatic little calves and to lose them to this horrible disease would be devastating. Our teams have acted fast and we’re doing everything we possibly can to help them fight it off.

Despite the ongoing and extensive efforts, staff at the zoo have warned that there are no guarantees of either calf’s survival.

Relatively little is known about EEHV. As well as those recorded in zoos, conservationists have discovered fatalities in at least seven countries across the Asian elephant range in the wild – India, Nepal, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Indonesia (Sumatra) and Myanmar.

Currently there is no vaccination against it but researchers are working to create a treatment that trains an elephant’s immune system in what to look for.

Chester Zoo scientists – backed by more than £220,000 of public donations, a major partnership with The University of Surrey, and an international collaboration of conservationists, have made real progress in the fight to find a cure – but sadly the battle is ongoing.

Scientists from Chester Zoo are at the forefront of this major international effort, which is critical if conservationists are to protect both wild and zoo elephant herds globally from the virus. If you would like to find out more information about EEHV, please read our frequently asked questions.

By offering these fantastic work placements, we are inspiring the next generation of scientists, conservationists and zookeepers! Our unique work placements offer students the chance to work alongside some of our experts within various teams at the zoo, including our science team and animal sections…

The strong family bonds of elephants is an attribute that many people resonate with and love about them. In the wild, both Asian and African elephants live in distinct social groups, where female elephants stay together in family groups for the length of their lives.

On July 14 1960, Dr Jane Goodall stepped foot for the first time in what is now known as Gombe Stream National Park, Tanzania, to study wild chimpanzees. Her ground-breaking research put the spotlights on the species and their remarkable abilities, such as toolmaking.

However, our closest cousins are now facing serious threats and are listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. With only 350,000 chimpanzees left in the wild compared to 1-2 million 100 years ago, protecting the species from habitat loss and the illegal wildlife trade is critical.

Stuart Nixon, Field Programmes Coordinator for Africa says:

“World Chimpanzee Day is something to celebrate! Humans have learned so much from studies of chimpanzees over the past 200 years: from increasing our understanding of our own evolutionary past to helping us advance manned space travel.

“Also, they possess astounding levels of intelligence, complex individual personalities, and rich and diverse regional cultures including tool use. Put simply, chimpanzees are absolutely amazing animals! I am proud and humbled to state that I am 99% chimpanzee.”

We are acting in four different countries to conserve chimpanzees and their habitat and are putting the spotlights on those projects today to celebrate World Chimpanzee Day.

Nigeria

Gashaka Gumti National Park (GGNP) is home to the endangered Elliot’s (or Nigeria-Cameroon) chimpanzee, the rarest of all chimpanzee subspecies. It’s believed to support one of the largest remaining populations, making it a high priority for the species’ survival. We have been supporting the protection of Gashaka Gumti National Park since 1994 carrying out the first surveys of the chimpanzee and working with the Nigerian Park Service and local communities. Since 2016 we’ve been leading vital conservation research in Gashaka. Since 2016, the team has carried out approximately 650km of exploratory surveys including monthly monitoring of chimpanzee populations and camera trapping in the rugged southern sector of the park.

We have also provided support to the Nigerian Montane Forest Project (NMFP) for over a decade. Based in Ngel Nyaki Forest reserve in the south-east of Nigeria, the NMFP team has conducted various research projects on an isolated population of Elliot’s chimpanzee, increasing knowledge of their ecology and nesting behaviour.

Gabon

We are now involved in an exciting brand new project in the Loango coastal forest region of south western Gabon, an area often referred to as Africa’s last Eden. In addition to being one of the last remaining strongholds of the western lowland gorilla, the region is also known to host populations of the central chimpanzee subspecies.

We are working in partnership with the Fernan-Vaz Gorilla Project to establish baseline data on the occurrence, distribution and density of chimpanzees and gorillas, as well as other threatened species, in a large, intact rainforest block north of the Loango National Park. The data collected will ultimately provide crucial information that could lead to the development of innovative conservation actions.

Democratic Republic of Congo

The eastern Democratic Republic of Congo is believed to support one the largest populations of chimpanzees remaining anywhere in Africa. It is thought to support up to 75,000 eastern chimpanzees in some of the continent’s most remote rainforests. The majority of surviving chimpanzees in DRC occurs outside of formerly protected areas where they are heavily threatened by bushmeat hunting and habitat loss.

Our efforts are focussed on supporting community-based monitoring and mapping of priority populations of chimpanzees, gorillas and okapi in this vast landscape. Chester Zoo experts have played a key role in developing IUCN action plans and innovative survey methods for great apes in this region.

Uganda

In Uganda, we recently completed the camera trap based surveys of the Semuliki National Park capturing images of the parks eastern chimpanzee population and assessing its distribution, numbers and threats to its survival.

In addition, since 2010 we’ve been supporting the New Nature Foundation (NNF) outside of the Kibale National Park, on their mission to conserve wild animals and their habitats through education and empowerment of local communities. To reduce the local reliance on forest woods, NNF has developed efficient stoves and biomass briquettes and distributed these widely in the surrounding communities protecting almost 2000 tonnes of rainforest trees from being cut down each year!

An important role of our applied science team is to observe the behaviour of different species of animals at the zoo and to report back their findings to the curatorial team that can then implement relevant actions if necessary. Victoria Davis, our Behaviour Officer, tells us more about JC the dominant mandrill that the team had been observing.

Our conservation and science work focuses on six specialisms with one of them being Wildlife Health and Wellbeing. This means that the various research projects conducted at Chester Zoo are designed to address and inform matters that may impact on the health and wellbeing of all the wildlife at the zoo.

Part of this includes to regularly evaluate our husbandry techniques but also to assess the habitat spaces and environmental enrichment we provide to our animals in order to provide evidence-based recommendations for the care of the species at the zoo.

Victoria explains in more detail:

“An animal’s behaviour can give us good insight into its health and wellbeing. Collecting behavioural data at the zoo provides us with information about how animals spend their time, what areas of their habitat they use most often and, in group-living species, how they are interacting with other individuals. This information is valuable for making husbandry and management decisions to ensure that an animal’s environment provides everything they need to be healthy.”

Victoria is one of our experts in animal behaviour and she regularly observes various individuals to collect data for the different animal teams. Studying the behaviour of the animals here at Chester Zoo is crucial and allows us to gain particularly useful insights into the way social species organise themselves.

The mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx) for example are known to be strongly affected by changes in their social structure and that can have a big influence on the group cohesion so looking at individuals’ behaviour can provide key information about the group as a whole.

Mandrills are very social, living in large mixed-sex groups in the wild. Within these groups there is a social hierarchy with the dominant individuals at the top and the subordinate individuals lower down.

A mandrill’s hierarchical position is likely to influence their behaviour. Dominant individuals, for example, tend to have easier access to a higher quantity of the more desirable and calorific food items, whereas subordinate individuals may have to be faster and climb higher to get hold of these foods before the dominant individuals do.

Collecting behavioural data on JC, the dominant male at the zoo, provided interesting information about the group of mandrills and the variations in their social structure.

To collect the data, the researchers recorded all of JC’s behaviour over hour-long sessions, collecting on average around five hours of data a week. They varied the time they observed him so that they could get a good idea of how his behaviour changed throughout the day. Alongside recording JC’s behaviour the team also observed what the rest of the group was doing.

Victoria continues:

By recording the behaviour of a group or individual animals we can get unbiased information about their activity levels and behaviour over time to ensure that any management decisions that are made can be based on evidence and are in the animal’s best interest.

To get an approximate idea of the ten other individuals’ behaviour, the researchers did a visual scan of the whole group at ten minute intervals and recorded all the different behaviours they observed.

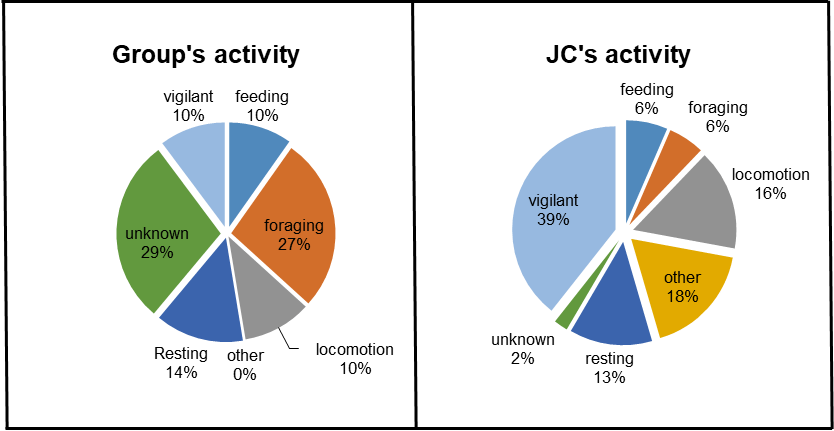

Comparison between the group’s activity and JC’s activity in September 2017

The team of scientists collected 125 hours of behavioural data over four months allowing them to get an idea of how the dominant male spent his time. They then classified the behaviours in the activity budget as ‘active’ or ‘inactive’ according to how much movement they elicited in the dominant male. For example, resting and being vigilant were classified as inactive behaviours as JC would often be sitting or lying down during these activities, whereas feeding, foraging and movement were categorised as active behaviours.

Figure 1 shows that JC spent almost 40% of his time being vigilant whereas the rest of the group spent only 10% of their time engaged in this behaviour. One hypothesis for this high proportion of vigilance-related behaviour conducted by JC is that as a dominant male he needed to take care of the group and so needed to always look for potential dangers or risks.

This figure also showed that the group spends more time foraging than JC did, and that could potentially be explained by the fact that he spent more of his time being vigilant and so has less time to forage. As a dominant male, JC also had access to the food prior to the rest of the group which could be another reason of why he didn’t need to forage as much as the others.

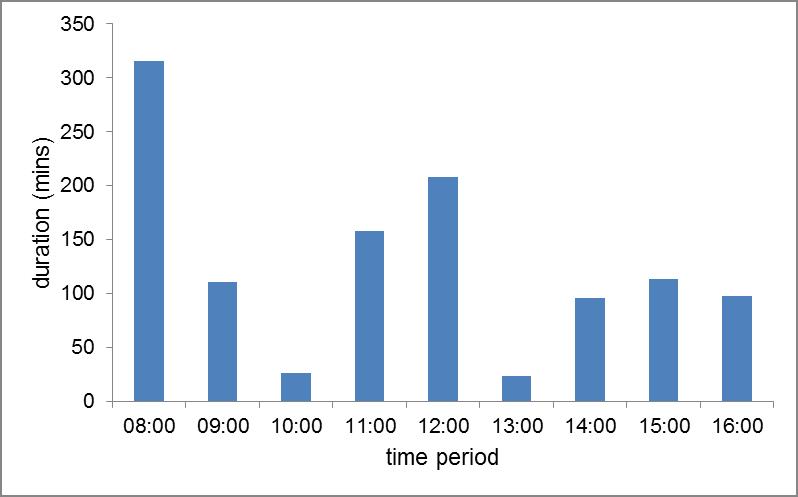

The researchers also looked at the temporal aspect of JC’s behaviour and they discovered that the dominant male was most active in the morning and around the middle of the day, just after the group is fed. It is around this time that JC was walking around exploring and searching for food.

This behavioural observation, in addition to providing us with precious information about the lives of the species at the zoo, also allows us to provide evidence-based recommendations for their care. In the case of JC for example, the primate team noticed early on that the dominant male was surprisingly inactive and seemed to be putting on weight.

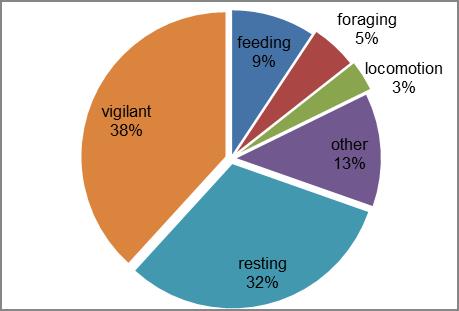

The data collected by scientists from the Applied Science team proved evidence that he was indeed spending 70% of his time either resting or conducting vigilance behaviours (see below image), which are both characterised as inactive behaviours.

JC’s activity in August 2017

JC’s activity in August 2017

To try encouraging JC to become more active, the primate team took various steps to encourage him to work a bit harder for his food by climbing higher and spending more time searching. They were able to do this by scattering higher calorie foods such as fresh vegetables in high parts of his habitat to encourage climbing, and sprinkling lower calorie foods such as grain on the ground to encourage digging and foraging in the substrate.

Chester Zoo’s Deputy Curator of Mammals, Nick Davis, explains:

“Once JC’s inactivity and subsequent weight gain was raised by the keepers, collecting behavioural data was the logical step in order to have the information needed to better evaluate his wellbeing. Along with daily keeper observations and veterinary expertise, it was crucial to provide a detailed assessment of his state of health. As the dominant animal of our mandrill group for over twenty years he has been critical in the success of our group, and this information allowed to manage him and ensure his quality of life was maintained.”

Despite the changes made following this study, JC’s health and behaviour remained a course for concern. During a detailed examination under anaesthesia it was discovered that he had developed osteoarthritis in several of his joints, which was deemed to be having a significant impact on his ability to move around, and so also to his wellbeing. These changes could not be reversed and so for wellbeing reasons the difficult decision was made to euthanise him.

JC was a hugely charasmatic animal and was popular both with visitors and the primate keepers, some of which had helped looked after him for the 20 years he was at Chester. Over his time he played an important part in the European Endangered Species Breeding programme, with his offspring being transferred to numerous zoos around Europe and the US, as well as being an important ambassador to educate millions of zoo visitors of the importance of mandrills and their threats in the wild.

EEHV doesn’t discriminate – it doesn’t matter whether it’s a two year old elephant calf at Chester Zoo, at a zoo in the USA or in the wild in Asia. We’re part of the global conservation community committed to the conservation of Asian elephants, so we will continue to carry out intensive research and work to discover more about this virus and how to treat it.

THANKS TO YOUR AMAZING SUPPORT SO FAR…

Your incredible donations have meant we’ve been able to move forwards with trying to find a solution to this deadly disease. Since the campaign launched in 2016, we’ve recruited Conservation Fellow, Dr Tanja Maehr to a post-doctoral position, run in collaboration with the University of Surrey and the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA).

Dr Tanja Maehr is working to tackle the threat this disease poses to young elephants and here she tells us more about working with Chester Zoo and the important research she’s carrying out:

“My research involves identifying some of the key mechanisms and key elements of the Asian elephant immune system, as little is currently known about this. This is necessary to identify certain cells that are involved in the innate and adaptive immune responses, to find a treatment against EEHV and identify what components of the immune system are involved in the defence against this virus.

“We also want to answer the question ‘why is it that only young elephants are susceptible to this disease‘; we will therefore try to characterise the immune responses from young and older animals too.

“I heard about the post-doctoral position through Chester Zoo’s Never Forget campaign and I became interested in the position as it’s quite a complex and curious disease, in the sense that it only affects young animals. From an immunological side, it’s a very interesting research question. EEHV is very complex as there are different strains of the virus.

“I applied for this research as I’m a zoologist and an immunologist and for me this meant I would come full circle in a way. As a zoologist, that’s why you start doing such a degree because you want to work with animals and then it becomes very scientific, but then you would like to apply that science directly to help animals.

“This research is vital in protecting elephants going forwards, they are an endangered species and other studies have shown that EEHV also occurs in the wild. So, if you factor out this disease then the population has a greater chance of survival. Plus it will help vital conservation breeding projects in raising young elephants successfully.

“Working on this project has meant two of my research interests are coming together; plus I want to collaborate with a zoo that does great work on the conservation of so many other species. I think Chester Zoo is leading the campaign against EEHV and really trying to find a solution to this devastating disease. I feel the zoo will support me in my research, through collaboration with other zoos and organisations that also want to tackle this virus.

“Several groups are already investigating this virus, and there are already efforts to collaborate to find a solution together. This is a really big and complex problem therefore it’s really necessary to collaborate and use joint efforts to find a solution.

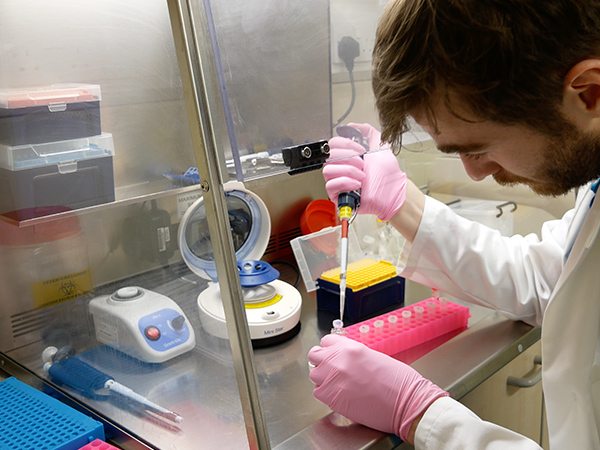

Dr Maehr is working to understand more about the elephant immune cells. There are different types of immune cells need to be characterised first, which can be done through a method called flow cytometry which isolates the cells using antibodies. Establishing an elephant’s antibodies that react with these cells needs to be discovered first, as currently little is known about this.

As part of the research we’re also going to use a real-time ‘polymerase chain reactor’ (PCR) method to characterise some immune responses and do some gene expression analysis and antibodies testing.

As a result of the incredible donations from the Never Forget campaign has meant we’ve been able to bring a PCR machine in house.

John O’Hanlon, Chester Zoo’s Laboratory Assistant, works in our endocrinology lab looking at the hormones of the different species at the zoo. He tells us why having this machine at the zoo is so important:

“We’re able to test for the EEHV virus using the PCR machine. PCR is a molecular biology technique which helps to amplify segments of DNA you want to analyse. It replicates the DNA by going through a number of cycles which help the amplification of the DNA.

“We currently look for EEHV DNA using the PCR machine, as early detection of the virus is critical for treatment. Symptoms don’t appear until later on when the viral load is already quite high and the PCR testing enables us to detect the viral loads quickly and start treatment.

“With having the PCR machine on site at the zoo, it really helps us to have a quick turnaround testing. If a blood sample or swab arrives to the vet lab in the morning, within hours we can have results! If an elephant is suspected of having EEHV we can carry out tests as soon as possible and pass the results on to the vets. We can do that day after day, sample after sample, until we’re 100% sure about the course of the treatment for the animal.

Dr Tanja Maehr, concludes:

“For the elephant species it’s really important that we find a solution because in the wild the populations are small, they’re fragmented. It is therefore thought that there is a greater chance disease could impact these smaller populations. It’s important to gain a sustainable population in the wild and in zoos to preserve our elephants.

“It’s an honour to be part of this project and to see the support that it has received so far, to see so many people wanting to help make a difference, is amazing.”

Join us in 2019 for the next Summer Stampede! Together with your friends and family, you can give a big boost to our Never Forget campaign and help us continue our work to find a solution to EEHV, by taking part in our sponsored walk.

The day is a special opportunity for you and your herd to walk around the zoo before we’re open to the public, with plenty of staff lining the route to answer any questions you may have on your way round. Find out more here.

“The Pantanal is the world’s largest wetland and, at its peak, is thought to cover an area the size of Greece! The region is a haven for wildlife lovers and I was thrilled to wake up on my first morning to the sound of wild hyacinth macaws squabbling with each other outside. The Lowland Tapir Conservation Initiative (LTCI) is studying tapirs across different habitats within Brazil.

“Over 95% of the Pantanal is privately owned and mostly used as agricultural land for cattle-ranching yet the study site is considered to be pristine tapir habitat. In contrast, the huge grassland expanse, known as the Cerrado, which covers most of southern Brazil, is being heavily targeted for human development. By comparing population trends and identifying threats to tapirs in different areas, the LTCI is able to work with stakeholders in order to help mitigate risks to them.

“During my time in the Pantanal, I helped the LTCI with its ongoing studies into the social and spatial ecology of lowland tapirs. Each morning, after a breakfast of milk and liver covered with breadcrumbs, we would head out and check each of the sixteen box-traps set throughout the 100km2 study area. The tapirs that we caught were anaesthetised in order to perform a full health examination and collect biological samples such as blood, body tissues and parasites. Certain individuals were also fitted with a radio-collar and, alongside the use of camera traps, we were able to monitor the movements of several animals. The LTCI has been collecting information on wild tapirs for over 20 years and this huge amount of data is helping to determine biological parameters such as the time interval between births, infant mortality rates and fertility rates within the population. This information is needed in order to determine how sustainable a population is likely to be.

Daytime temperatures were regularly above 40°C, making it hard and tiring work but, having worked with several lowland tapirs at the zoo, it was a wonderful and humbling experience to get hands-on with those in the wild.

“My afternoons and evenings were then spent working alongside members of The Giant Armadillo Project. Very little information is known about these labrador-size, prehistoric-looking creatures but studies suggest that their wild population has reduced by 30-50% over the past 30 years. The Giant Armadillo Project is helping to discover more information about the ecology of this rare and elusive species in order to help identify and reduce the threats to it.

“Each day, as the sun started to disappear over the horizon, the team and I would head out on the back of a 4×4 truck, using radio-telemetry to locate previously identified armadillos. If an unknown armadillo was found, we would carefully capture and anaesthetise it in order to perform a full health examination, collect biological samples and place a radio-transmitter and GPS device. Such information and observations have shown that male armadillos may have home ranges of up to 40km2 and that the burrows they dig can be used by over fifty different species of mammals, birds and reptiles. The discovery that giant armadillos are such important ‘ecological engineers’ means that by preserving them in an area, several other species will also benefit and hopefully thrive.

“Having wanted to visit the Pantanal since I was a young boy, it was a huge privilege and a dream come true to see the amazing work being carried out by both projects and to appreciate how Chester Zoo is helping to Act for Wildlife around the world. As well as tapirs and armadillos, I was fortunate to have encounters with wild giant anteaters, caiman and capybara plus so much more! It was a truly wonderful experience which I will remember forever.”

Yenny has spent the last three months with us at Chester Zoo and with some of our colleagues around the UK to develop her knowledge and skills. She shares her highlights with us and tells us more about what she learned in the UK.

“Before coming here I arranged my schedule with Dr Steve Unwin, Chester Zoo Veterinary Officer, so that it would reflect what I needed. For example, my veterinary centre in Indonesia has some bronchoscopy equipment but we don’t know how to use it so I asked Steve if he could arrange for me to get trained on that topic. He put me in touch with Romain Pizzi a specialist Veterinary Surgeon working for the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland in Edinburgh and I had the opportunity to go do some endoscopy and bronchoscopy training with him!

“I talked to Steve about the things that were really needed in my centre because I really wanted to learn skills that could help me develop it further. That’s why I went to Cardiff and trained to conduct heart scans. At the centre we have five big orangutans which we cannot release for various reasons and that means that they’ll stay at the centre so we need to be able to monitor their hearts. Normally big orangutans would be going in the forest very far away but as we keep them at the centre they don’t have access to as much forest as they would do normally, so they are more at risk of getting various heart diseases which is why I need to be able to do a good scanning of their hearts.

“During my time here I also had the chance to go to four conferences. The first one was the Veterinary Ethics Conference at Edinburgh University which focussed around the topic of animal well-being in practice. Then I gave a Members Talk at Chester Zoo with Ian Singleton, Director of the Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Programme (SOCP), and Helen Buckland, Director of the Sumatran Orangutan Society. We talked about the orangutans in Sumatra especially and I talked about the relationship between SOCP and the Chester Zoo led Orangutan Veterinary Advisory Group (OVAG).

“Then I went to the British Veterinary Zoological Society Conference at ZSL London Zoo where I presented a poster on the post-release health assessment for orangutans that I conduct in Jantho. I also attended Chester Zoo’s Trade Off Annual Conservation Symposium – that was interesting because it was focused around the topic of illegal wildlife trade and we have a lot of it happening in Indonesia!

“At Chester Zoo I also had the opportunity to go on section with the Primate Team. I learned a lot about the husbandry and not just for the orangutans but about for other primates as well.

“Looking at the diet for the animals is very important so the team showed me the diet of different primates and they all had a different menu. This was very useful for me because when I go back to my centre our orangutans will be going back to the forest so we should try to adapt their diet to prepare them.

“Overall I really enjoyed traveling around the UK and loved the cultural exchange I had the chance to experience. I loved the British food but I was faced with one dilemma though: to decide if I should first put jam or cream on my scones!”

Chester Zoo has been supporting the fish ark in Morelia, Mexico since 1996, long before starting work at the zoo in 2014 I had been aware of the work of Omar Dominquez and his team within the field of Goodeid conservation.

Goodeids are a subfamily of fish comprising of 41 species, almost all are endemic to the mountainous volcanic central state of Michoacan, several of the species are already extinct in the wild and many more are threatened by various factors including pollution and introduced species out-competing them for food, space and often predating on the Goodeid offspring.

When I was told that I would be visiting Morelia to see the work first hand, as a ‘Fish geek’ my excitement could hardly be contained! To visit a beautiful country to fish for species I had often read about in books and to represent Chester Zoo at the same time – it was almost a dream come true. I travelled with my colleague and fellow aquarist Nadia Jogee (read Nadia’s blog here).

Day 1

After arriving in Morelia late in the evening, our first full day was spent acclimatising ourselves to the beautiful city of Morelia. We enjoyed watching the relaxed Mexican way of life and the way Mexican people use these open public spaces for socialising and relaxing with family and friends.

Day 2

Today we were to visit the University and Aqua lab for the first time, the team at the aqualab consists of several departments and we met and worked alongside many people, including aquatic technicians, parasitologists and limnologists.

Day 3

We travelled back to the aqua lab to meet team leader Omar Dominquez and Rodolfo Perez Rodriguez. Omar had just returned from a field trip to the Gulf of Mexico where he was collecting marine fish from an offshore reef, he was extremely welcoming and gave us an overview of the tequila splitfin (Zoogoneticus tequila) project. He then invited us to accompany him to the university’s botanical department. Here the aqualab have two semi natural ponds which are filled with three species each.

Within the pool containing tequila splitfin several hard working students were busy setting fish traps and were collecting and sorting over 700 individuals of tequila splitfin to take back to the aqualab, undergo a period of quarantine before eventually being translocated back to the Rio Teuchitlan for reintroduction. We were allowed to help with this work at the semi natural ponds.

Day 4

We were collected from our hotel at 5am and drove five hours in a North West direction to the town of Teuchitlan and the Rio Teuchitlan, the type locality for the tequila splitfin – incidentally the fish did not get its name from the alcoholic drink produced in this area, it received its name from the nearby ‘Volcán de Tequila’.

The Rio Teuchitlan is the habitat of tequila splitfin and the location of the reintroduction of the same species. It’s a short river around 1.5 miles in length, it’s source is an underground spring located in the park known as ‘El Rincon’. The site has been developed as a water park for local residents to relax and swim. The crystal clear waters are an ideal reintroduction site and the residents of Teuchitlan have a vested interest in protecting this site from pollution.

Day 5

Still in Teuchitlan we headed to ‘El Rincon’ for the second part of the project; the University team had arranged to give a presentation to the locals as part of an ongoing project. Almost all of the residents of Teuchitlan now know and recognise the university and understand the work that they’re doing in this area. The local residents are very proud to host this work and many are actively involved in protecting the environment and ensuring that ‘El Rincon’ can be enjoyed by both local bathers and the native wildlife.

The trip was a complete success! We were able to witness first-hand the work that we had read so much about in several reports, however for me the lasting impression is the shear dedication of the Mexican scientists working in the field! They work tirelessly and battle numerous obstacles to protect the goodeid species that are found exclusively in the central Mexican states.

The tequila splitfin reintroduction is nearing the end after almost five years of hard work and dedication, the first fish are now being reintroduced and only time will tell if this project is successful. The planning has been meticulous and the ground work finished, now it is time to start to think of the next project! Many other species of goodeid are critically endangered and using the knowledge gained from this project, future reintroductions will certainly be possible. None of this could be possible without the support of Chester Zoo funds and encouragement, just another reason I am SO proud to work for the zoo.