Tag: Animal health and wellbeing

Having met our Veterinary Officer, Steve Unwin, who is heavily involved in the Orangutan Veterinary Advisory Group (OVAG), in 2009 at the first OVAG meeting Yenny has since become a leading member of the steering committee. OVAG is a network of experts working in orangutan conservation, and aims to bring together those working with the species to share expertise, knowledge and the exchanging of ideas to move forwards with effective orangutan conservation.

Yenny explained that OVAG is like a family, allowing Indonesian vets working with orangutans to share their cases and work towards improving the standards of all orangutan centres in the country. Below she tells us a bit more about the threats faced by orangutans in her country and her passion for this incredible species:

“I’m currently working as a Senior Veterinary Manager for the Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Programme (SOCP) in Sumatra, Indonesia, and that means that I supervise the SOCP vet team.

“The SOCP was established in 2001 and is part of Yayasan Ekosistem Lestari (YEL). SOCP has a lot of programmes focusing on the Sumatran orangutan which means we do not focus only on rehabilitation; we are also conducting research and working on issues such as habitat destruction and restoration. We also raise awareness within the local communities.

“When I look at orangutans, they just look different from the other animals. They are very intelligent and they have similar expressions as humans but that also makes working with that species very challenging but being Indonesian, I want to play a role in keeping this special species safe.

“The Sumatran orangutan is classified as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List. They usually come to our rehabilitation centre because their habitat has been destroyed by the deforestation process. Many orangutan infants are now coming to our centre because people are killing their mums so they can have the babies as pets. We confiscate them on behalf of the Forestry Department.

“People are selling the babies to people who then keep them as illegal pets. Once rescued or confiscated, they need to spend months sometimes years in quarantine to learn to become wild orangutans again and to make sure they don’t carry any human disease back to the forest. It makes me so happy that we are so successful returning these orangutans successfully back to the wild.

“The number of confiscated animals from 2001 to now, is totalling 349 orangutans. We released a total of 168 individuals at the reintroduction station in Jambi and 102 in Jantho and currently we still have 51 orangutans at the quarantine centre.

“At the moment we are developing a new project called Orangutan Coffee. This project is taking place in the middle part of Aceh, Indonesia, and we are planning on selling the coffee from organic plantation based there and then export that coffee to Switzerland, England and other countries. The benefit would then in turn help raise money for other SOCP’s programmes.”

We have been supporting OVAG for a number of years and Steve Unwin, our Veterinary Officer, has been involved working towards becoming a major force in shaping conservation medicine work across Indonesia and Malaysia.

We’ll catch up with what Yenny has been up to at Chester Zoo and our colleagues following her work placement in the UK.

After few years working with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) on various projects including turtles, wetlands and wildlife enforcement, Ee Phin realised how crucial engaging with people is to the conservation world. Ee Phin explains:

“Actually, conservation is more about managing people instead of wildlife. If you can work together with different stakeholders and gain their trust, it becomes extremely valuable for advancing conservation efforts. Each stakeholder can contribute their strength and jointly make a project a success.”

Without good collaboration, conservation may be stalled.

A few years ago, a new opportunity presented itself to Ee Phin: a PhD offer to work with Dr.Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz, the principal investigator of a project called Management and Ecology of Malaysian Elephants (MEME). The Malaysian conservationist didn’t hesitate and enrolled as a PhD student at the University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus and later on became a Chester Zoo Conservation Scholar.

Ee Phin continues:

“The project was very exciting because it was all about tracking wild elephants and using faecal endocrinology to study them. I thought that was really interesting because it is very difficult to track or even see wildlife in the rainforest so using GPS collars really gives us a new window to observe and follow these animals.

“Also I was really interested by the topic of faecal endocrinology because it seems to be a very diverse tool! If you learn the technique you can apply it not only to elephants but to other wildlife as well.”

During her PhD, Ee Phin looked at glucocorticoid metabolite concentrations (a class of steroid hormone) in wild Asian elephants’ dung. Glucocorticoids modulate daily levels of energy and are also involved in stress responses. She continues:

“If an accident happens out of the blur and you need to either ‘fight or flight’, the first wave of hormones will give you that adrenaline rush. Those first hormones are really quick acting hormones but glucocorticoids are released in a second wave of hormones a few minutes later and its effect on the body lasts longer. It is easier to study glucocorticoids in faecal as its molecules are more stable thanks to its cholesterol ring.

“Translocation is very relevant in Malaysia as lots of large areas are being converted to plantations and elephants are pushed away further and further. Villagers and plantation owners are not willing to tolerate the losses caused by elephants, and they pressured the authorities to translocate the elephants.”

Before 1970s, elephants in Malaysia were considered agricultural pests and were often killed. The situation shifted in 1974 when the country signed a new Wildlife Act protecting the iconic species and the Wildlife Department created an Elephant Capture Unit.

“Instead of culling the troubled elephants, the Unit started capturing them and transported them out to release them in large forests. It has been estimated that a few hundred elephants have been captured and moved so translocation could potentially have a large impact on the wild population.

“Assessing the impact that those translocations have on the species is essential but elephants are hard to track in the rainforest so gathering data is challenging. That’s why MEME decided to focus on Malaysian elephants and managed to raise enough funds to buy 50 GPS collars to enable the team to track the pachyderms in the forest.

“Sometimes if they don’t move they might be just few feet away and you wouldn’t know they are there. It’s very surprising but in the forest the elephants, even though they are so big, can move quietly or hide if they want to!

“Having the opportunity to deploy GPS collars on the translocated elephants opened a window to follow the elephants and collect their dung. However, once collected the remaining challenge was to know how long the hormone metabolites would stay stable.

Most people recommend to collect samples as soon as possible, potentially right after the elephant defecates, but that’s not possible for me because these are wild animals and they can be dangerous.”

This is why Ee Phin decided to carry out research to determine how stable the glucocorticoid metabolites in dung over time are and in different environment conditions. Collecting 80 samples of fresh dung within housed elephants and assessing their hormone levels straight away, the Malaysian researcher then measured hormone metabolites in those same dung piles within 30 minutes to two days after excretion.

Ee Phin explains:

“I found that the hormone metabolite concentrations are stable up to eight hours after defecation. After that it can go up or down but most of the hormone metabolites will increase. This unique investigation also assessed the impact of a contrasted environment to see how the rainforest conditions could impact on the metabolite levels.

“For me the biggest output I shared with the scientific community is that basically we have to be aware of time, otherwise we might interpret our data in a wrong way. Validation experiments are very important when studying faecal endocrinology, to ensure we are interpreting the right data and not some artefact of the environment.”

As part of her PhD, Ee Phin also assessed the differences in hormone levels in translocated elephants and in non-translocated elephants. Since finishing her PhD, she has continued her research in Malaysia and she is now working as a lecturer in the newly opened School of Environmental and Geographical Sciences.

One of the new MEME PhD students is currently working on the movements of translocated elephants and he actually found that there is a movement difference between translocated and non-translocated elephants in terms of road crossing behaviour.

Ee Phin concludes:

My next step is to link my hormone study with this movement study to actually get a stronger support for us saying that translocations do have an impact on the elephants’ physiology and behaviour. I’m hoping that with our studies people can start thinking at how to mitigate these physiological impacts.

For more information on Ee Phin work follow the link below: Wong, E.P., Yon, L., Purcell, R., Walker, S. L., Othman, N., Saaban, S., Campos-Arceiz, A. (2016) Concentrations of faecal glucocorticoid metabolites in Asian elephant dung are stable for up to 8j in a tropical environment. Conservation Physiology, 4(1), 1-7.

Together with the Government of Bermuda’s Department of Conservation Services and Manchester Metropolitan University, we’ve been working with Heléna to study the Bermuda skink as part of her PhD in Biodiversity Management at The University of Kent.

“I’m looking at the conservation and population status of the critically endangered Bermuda skink. There is estimated to be only 2,500 remaining in the world and their population has been in continual decline since 1965.

“The species is listed as critically endangered by the IUCN Red List and faces multiple threats on Bermuda due to several deliberate and accidental introductions of species such as rats, cats, crows, cane toads, chickens, various species of anoles, geckos, kiskadees and yellow crowned night herons. Coastal developments, invasive plants and natural disasters are other factors impacting the species and causing habitat fragmentation and destruction.

Not much is actually known about their ecology making Heléna’s work crucial to develop a better understanding of this endemic lizard species.

“Another major factor is litter being improperly discarded and washed up as marine trash in the skinks habitat. Empty bottles act as lethal traps for small insects such as woodlice or cockroaches that are attracted by the sugary fluid left inside, which in turn attracts the skinks. As the skinks have clawed feet they can’t escape and quickly die of heat exhaustion.”

The research Heléna is currently conducting is vital to find out where the skinks remain on the different islands of Bermuda but also to assess how many individuals are left in the wild and what the main threats to the species are. This information is crucial to create a plan of action for the future.

For the past few weeks, Heléna has been carrying out field surveys at four different sub-populations: Castle Island, Nonsuch Island, Southampton Island, and Spittal Pond. Taking a boat and accompanied by a team of researchers, she goes to the field sites and set up large glass jars filled with rotten sardines and cheese to attract the skinks.

She tells us more:

“I normally use 20 to 80 traps which are checked hourly during a five hour period and take genetic and faecal samples and morphometric measurements for all the individuals we manage to attract. The traps are placed 5 to 20 meters apart as skinks are thought to have a very small home range of around 10 metres. Other information such as the individuals’ stage of life, gender and missing digits or other mutilations are also recorded as they give precious information on the ecology of the species and can indicate high predation in the area.”

So far, Heléna has some interesting preliminary results indicating that skinks have not been entirely isolated on these offshore islands. It seems that some individuals living in rock crevices fall into the sea with bits of vegetation during storms and hurricanes and then drift to the next island increasing the gene flow between these vulnerable sub-populations.

Not only is this project looking at how Bermuda skinks are doing in Bermuda but it is also closely related to the work carried out at Chester Zoo. Heléna explains:

At the moment, the conservation breeding at Chester Zoo aims to improve the husbandry of Bermuda skinks for an eventual conservation breeding programme. However, once I find out where the skinks are absent or declining on the island and why, in the near future we could be reintroducing skinks back to historic sites in the wild therefore both the PhD and breeding programme are complementary elements.

What are you fundraising for?

I’m running the marathon to raise money for our Never Forget campaign to fight EEHV.

EEHV is a devastating virus that kills young elephants both in the wild and in zoos. Unfortunately five calves born at Chester Zoo have died from the virus. We currently have three young elephants within the herd so EEHV is never far from the elephant team’s thoughts.

We are doing what we can with the knowledge we already have but more research is required to improve our understanding of the virus and how best to treat it.

Why did you choose to do a marathon?

This will be my second marathon, I ran my first in 2015. Thought it was about time I conquered another one as I enjoy challenging myself.

Why Loch Ness?

I’m originally from Glasgow so have been keen to complete a Scottish race. I chose Loch Ness because I thought the gorgeous scenery would be a welcome distraction when fatigue starts to set in.

How has the training been going?

In July I completed my first sprint triathlon so my training has involved not only running but also swimming and cycling. Now my focus is to gradually increase my mileage up until race day.

At times it has been difficult keeping to my training routine but running in aid of such an important cause has kept me motivated.

Update

She did it! Katie conquered this monster marathon!

She faced terrible weather and a very tough race, but she made it to the finish line and raised over £400. Well done Katie!

Thank you everyone for your support.

There are two internship options – a three month and 12 month placement – both of which involve working with different teams across the zoo on a voluntary basis carrying out research and . As part of their time here, the interns gain a better understanding of the role of a modern zoo, commercial aspects, interview skills, animal enrichment, plus a range of other topics! Many of the interns are studying a degree or masters and carry out the internship during their placement year, to support their degree.

Through supporting future generations to develop their knowledge and inspiring them to want to Act for Wildlife, not only are we supporting them to develop their studies, we’re working towards our mission of preventing extinction.

This week we’re saying ‘bye and good luck’ to our latest team of interns, as well as welcoming the next group. We managed to catch up with some of our research interns to tell us more about what they’ve been working on over the past 12 months and what they’ve taken from it.

Behaviour and Welfare Intern

Lydia is a zoology student who has always had an interest in animal behaviour. When she saw the zoo advertising a Behaviour and Welfare Internship she knew she had to apply. Read more from Lydia Underwood, here >

Bird Intern

Abbie had to do a one year placement as part of her degree and after doing an assignment at university that sparked her interest in birds, she decided to come to Chester Zoo to do her internship. Read more from Abbie Buxton, here >

Visitor Engagement on Islands

Elinor is studying a Biology with Science and Society degree and is very interested in social science, she decided to come to Chester Zoo to do her placement year where she looked at visitor engagement in our Islands area. Read more from Elinor Bridges, here >

Endocrinology Intern

Alice is a Masters student who came to Chester Zoo to do her industrial placement year. During her degree she went on various scientific expeditions doing fieldwork but wanted to try something different and applied for a placement in our endocrinology lab. Read more from Alice Clark, here >

Nutrition Intern

Jasper is studying a degree in Zoology and was determined to learn something new during his placement year. Chester Zoo provided him with the opportunity to work on a topic he didn’t know much about: animal nutrition. Read more from Jasper Hughes, here >

Bird Curatorial Intern

Jill is studying a degree in Wildlife Conservation and heard about Chester Zoo’s internships when she was really young and so was extremely happy to be selected as our Bird Curatorial Intern. Read more from Jill Vevers, here >

Reptile Intern

Jonathan is studying Biology and having done an internship on bushbabies prior to his placement year, he decided to apply for our primate internship. However, his passion for reptiles was noticed and he ended up being selected as our Reptile Intern instead. Read more from Jonathan Holman, here >

There are likely to be more people watching your nearest Premier League football match this weekend than there are elephants left in the wild. This magnificent species is threatened by habitat loss, poaching, disease and direct conflict with humans. We are working in India to protect the species from human-wildlife conflict, while closer to home we are part of a breeding programme focused on sustaining an insurance population.

Our elephant herd here at the zoo are a close knit family. This is backed by scientific research which has shown that social bonds between individual elephants has a big influence on cohesion in the whole group and consequently the health and well-being of the herd. Richard Fraser, elephant assistant team manager, spends his working day with seven staff and eight elephants. Here, he explains why he loves his job…

A tropical start to the chilliest morning…

“One of the many good things about working on the elephant section is the heat. Our elephant house stays at around 20 degrees which means it’s warm all year round and when you travel to work in the middle of the cold British winter, there’s nothing better than coming into a toasty habitat. The day starts with the team getting together to discuss plans for the day ahead.

The morning is the best part of the day

“I have to say one of the best parts of the day for me is first thing in the morning when we check the herd. We never enter the elephants’ habitat, so there is always a barrier between our team and the animals. Yet we still have to make sure they are fit and well. It is important that we build strong bonds with the elephants so that they respond well and allow us to carry out vital health checks. We train our elephants as early as possible because you never know when you’ll need urgent medical access. With new elephant calves we get them used to the keepers being around and coming into our husbandry areas.

“We have a special extended area to the main husbandry pen just for calves, which gives us better access to them while mum remains near-by watching what we’re up to. If necessary we can take blood samples and administer drugs in a calm and cooperative manner that both mum and calf are comfortable with. When the calves are about 6 months old we take weekly blood swabs from the ear to check for any presence of Elephant Endotheliotropic Herpesvirus (EEHV). This deadly virus affects young elephants and is a major threat to their future survival in the wild and in zoos. It typically strikes around weening age and is very fast acting. As there is currently no vaccine for the virus we do weekly blood tests so that if the virus is found we can begin anti-viral treatment. Meanwhile our scientists are fighting against the clock to develop a cure which could protect the species globally.

Poo glorious poo

“If you’re a zookeeper then poo is a big part of your life, you’re immune to the smell and it’s normal to talk about it over lunch. Once we have completed the daily health check then it is time to clean out. While our elephants are outside we clean the indoor habitat and while they are inside we clean their large outdoor paddock. Our work is not completely about poo though! We also spend time forming sand mounds, creating bark piles and digging out mud wallows to provide an interactive environment for our herd. A big part of our job is to come up with new and innovative ways of keeping the elephants busy while at the same time encouraging natural behaviours, and it’s a task I relish. All the more so as it usually involves us spending time driving around on the section tractor and excavator before watching the elephants explore what we’ve created.

I love Asian elephants and enjoy working with them every day. Working here means I play a vital role in conserving this beautiful species. As well as working with the herd in the zoo we also work in India trying to protect the species in the wild.

Most memorable moment

“One of the major threats to the future of Asian elephants are the encounters between human and elephant populations. The forests of Assam in North East India provide one the last strongholds for the Asian elephant but these forests have some of the highest levels of human-elephant conflict in the world. Activities such as deforestation are bringing elephants closer to humans so they often end up travelling through villages, destroying homes and crops. We are working with the local communities to develop ways for them to live safely alongside wild elephants, while being able support themselves and their families.

“We formed the Assam Haathi Project with our partner organisation Ecosystems-India over 12 years ago. The project works with more than 24 villages in the Sonitpur and Goalpara districts of Assam in India, working within the communities to create deterrent measures for the elephants such as electric fences, spotlights and chilli smoke, but also working with the local people to improve livelihoods. I was lucky enough to travel there in 2014 and get first-hand experience of the problems people are facing. It is critically important that our hands on experience with the species here is used to the combat the problems faced in the wild. The dedication shown by the conservation team out in India as well as the enthusiasm and gratitude from the local people has shown me how, with a little extra help, a huge difference can be made to so many lives. In turn this is then helping to conserve the remaining populations of elephants that are found in areas such as Assam.

Finding out more about this endearing species

“One of the highlights of my week is watching our elephant herd sleep. We’ve been observing the social affiliations of our herd for two years now to give us an insight into our elephant’s psychology. We do this by observing the herd during the night, giving us a unique insight into how they react without us around. Using a camera system that is already installed around the house, a member of our team watches the sleeping patterns of the herd over a 12 hour period from 7pm to 7am, twice a week.

“We hope our work monitoring their social affiliations will develop and grow. We are at the forefront of elephant wellbeing and the work we are doing here will enable us to gain a deeper understanding of this truly fascinating species.

“Right now, Asian elephants are under threat but we won’t stand back. Conservation is critical, in zoos and the wild. It’s time to Act for Wildlife.”

Donate to We Will Never Forget

Join the fight now and 100% of your money will support invaluable research and help us put a stop to this devastating virus.

Luiza Passos has been working with the golden mantella for four years, a small critically endangered orange frog endemic to Madagascar. This colourful species is mainly threatened by overharvesting for the pet trade and by habitat destruction due to legal gold mining.

Her PhD with the University of Salford supports the conservation work we’re carrying out on the ground in Madagascar, with our partners Madagasikara Voakajy, as well as the work our keepers are doing to protect the species at the zoo. Her research involves measuring the characteristics of golden mantella to increase our understanding of when the optimum time would be to potentially release individuals into the wild.

Dividing her time between field work in Madagascar and observing the population of frogs at Chester Zoo, Luiza assessed factors known to be crucial for the survival of the species in both environments. These factors include their colouration, their calls, their anti-predator behaviour and the bacteria present on their skin. Luiza told us more about the data she collected as part of her research and what she discovered as a result:

Frog calls

The frogs’ calls were recorded using a microphone and the wave forms were then compared between the population at Chester Zoo and a population of golden mantella in Madagascar. Luiza discovered that the sounds of the zoo population were different to the calls from the Madagascar population. However after conducting a playback study to assess both groups of frogs’ reaction to each recorded call, she discovered that despite the sound being slightly different, they still recognised the calls from other populations. The Chester Zoo population responded to the calls from Madagascan individuals; the males were observed fighting and calling back to the recordings, reflecting natural breeding behaviour.

Luiza carried out further research into the calls which consisted of putting the frogs on one side of a mat with a speaker positioned on the opposite side (see video below). The aim was to assess the speed and route that the frogs will take in reaction to the call being played. The Madagascar population responded in a similar way to both their own calls and the dialect calls, while the Chester Zoo population showed a preference for their own calls.

Anti-predator behaviour

One of the most important survival factors in frogs is the ability to detect potential predators and to show anti-predator behaviours. Golden mantellas, like many other frog species, show a specific behaviour, called tonic immobility (TI), or thanatosis, when exposed to predators. This is where the animal ‘plays dead’ to divert the attack of a predator, allowing the individual the chance to hop away. Luiza found that the Chester Zoo population had the same responses as those in the wild; meaning there may be an intrinsic mechanism that triggers that kind of behaviour. It shows that Chester Zoo’s population of golden mantella would be able to respond to predators appropriately, should they be reintroduced into the wild.

Colouration

Assessing the colour of each frog isn’t possible using just the human eye, meaning Luiza used a spectrometer which was able to quantify differences in the colour of each individual frog. Luiza discovered that animals in the zoo display a natural colour; this colouration is impacted by factors such as UV light and temperature. This means the findings show that the zoo environment is reflective of their natural habitat, allowing them to develop the same colours as the population in the wild.

Microbiology

Bacteria present on the golden mantella’s skin are an essential defence against diseases in the wild and play a crucial role in survival. The origins of these bacteria are unknown but they could be acquired from the environment, from the males fighting or even from when the females lay their eggs. Luiza swabbed frogs from the wild and from Chester Zoo to compare their bacteria diversity and abundance. We found out that the zoo animals have a lot less bacteria, both in terms of species diversity and abundance. This means that in the case of a reintroduction, these frogs would need to have their immune systems boosted before being released and that can be achieved with the use of probiotics.

This research highlights the similarities and differences between the population of golden mantella frogs at Chester Zoo and population in the wild in Madagascar. It has been shown that the individuals from the zoo have the right colouration, display the appropriate anti-predator behaviours and, despite favouring their own calls, react to wild calls. The frogs in the zoo presented fewer bacteria than those in the wild, meaning that they could be at risk to develop diseases if released without the use of probiotics; which can help boost their immune systems until they get the appropriate bacteria in their new environment. The next step for this research is a soft release to see how we could mitigate these differences to ensure the individuals are ready to be released in the wild in future.

Saving the northern bald ibis from extinction

During the summer of 2016 we were delighted to breed seven bald ibis chicks. A critically endangered species, the northern bald ibis is part of a European breeding programme led by zoos. With an estimated 115 pairs of birds left in the wild the northern bald ibis is on the brink of extinction. This is the second breeding success for our bird keeping team. The first of the chicks bred here were released to the wild in February and the latest will be released early next year. We’re hoping that by introducing these birds to a protected site in Southern Spain we’ll take big step forward in reversing the decline of the species.

Saving turtles with your support

You’ll remember our recent appeal to help our partners at the Katala Foundation project in the Philippines after they confiscated over 3,500 live Palawan forest turtles. The future looked bleak for the turtles that had fallen victim to the illegal wildlife trade and were destined to be sold in China. We’re delighted to report that thanks to your support and the hard work of the team working on the ground at the Katala Foundation, 89% of the turtles were saved and have now been reintroduced in to the wild. Thank you!

Proud of our volunteers making Wildlife Connections

All year we’ve been focused on giving people across the UK the skills that they need to deliver real conservation in their own back yards. We’ve trained 57 wildlife champions to go out, create wildlife friendly habitats and to train their local community to do the same. Plus, we’ve had hundreds more people sign up and download our ‘how-to’ guides to create their own Wildlife Connections. It’s not too late to sign up for a ‘UK wildlife friendly’ start to 2017. Why not make it your New Year’s resolution?

We Will Never Forget

This year we launched our ‘We Will Never Forget’ campaign to raise funds to support research in to the deadly EEHV virus which threatens young elephants in zoos and all over the world. For us, this was personal after we lost elephants to the virus. We’ve been overwhelmed by your support; to date we’ve raised £100,000 which has funded a post-doc research position dedicated to finding a cure the virus. Please help us to keep this vital research going and enable us to carry out more research in the wild by making a donation.

Supporting the next generation

We’re really proud to be helping to train the next generation of conservation scientists. We’re currently supporting 17 Chester Zoo Conservation Scholars from nine institutions, who are working on a range of species and topics in the zoo and out in the wild. This year, Conservation Scholar Ee Phin Wong completed her PhD research and has now gained a post-doctoral position. We’re really looking forward to working with more scholars in 2017.

Find out more about how our community of committed experts and enthusiasts are making a real difference to conservation by signing up for our e-newsletter or following us on social media.

One year ago, Chester Zoo conservation scholar Jacqui Morrison started her PhD research looking at the physiological and ecological effects of limiting wild African elephants in National Parks within the mountain forests of Kenya.

Here she tells us more about her recent field trip:

“This PhD was a great opportunity to apply theory that I had learnt during my previous undergraduate and postgraduate degrees into practise to help protect one of the world’s largest and iconic mammals.

“Kenya has a rapidly increasing human population, this has resulted in large areas of land that were traditionally used as seasonal migration routes for elephants being converted into agricultural land. When humans and elephants co-exist, conflict between them such as property damage, crop-raiding and human injury can occur, this can result in retaliation killings to protect livelihoods and human life.

“As a method to reduce this conflict and protect both the elephants and the local communities, a fence was built around the Aberdare National Park to keep the elephants within the park; I am studying if there are any effects of the fence, both to the elephants themselves and also to the vegetation within the national park.

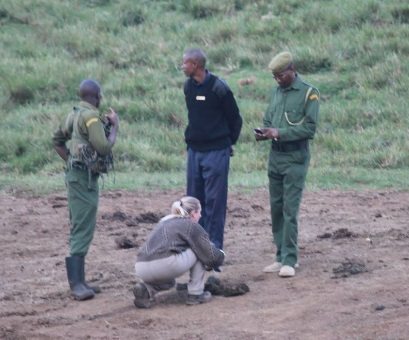

“In June this year I set off on my first field trip to my research site in Kenya where I spent three months collecting data for my study which has many different components; including, observing the elephants in order to get estimates of population numbers, gathering demographic information of the groups including total group size, age structure and sex ratios and finally collecting vegetation data to accompany the remote sensing data I had been working on whilst in the UK to then be able to assess elephant damage.

“Due to the dense vegetation in the montane forest, a herd of elephants could be only 50 meters away but not be visible to people, so the majority of observations were conducted at watering points and using camera trap footage.

“The first task was to enter the Aberdare National Park in order to place a number of camera traps that were set up in a grid system, due to the terrain and high altitude this was physically demanding and challenging. But when in the untouched, closed-canopy of the forest, the beautiful scenery made you feel privileged to be alone with nature.

“Once all of the camera traps were set it was time to start looking at whether confinement was having an impact on the physical condition of the elephants. To do this I had to observe individual elephants and record the body condition scores on a scale of 1 to 5 of adult and sub-adult individuals within the population using a scoring index that was validated in another study.

“To continue with monitoring the physiological state of the elephants, I had to locate fresh dung from observed individuals which was particularly challenging within the environment due to poor visibility and a difficulty in finding elephants as this year the climate conditions were unusual for that time of the year; being colder and wetter than usual. It is thought that the elephants had moved into areas of thick bamboo to take shelter. Once we had located some elephants and had observed them defecating, I was able to go in and collect a small sample of the dung under the supervision of wildlife rangers. Due to the difficult conditions, being able to collect the dung samples was an exciting moment!

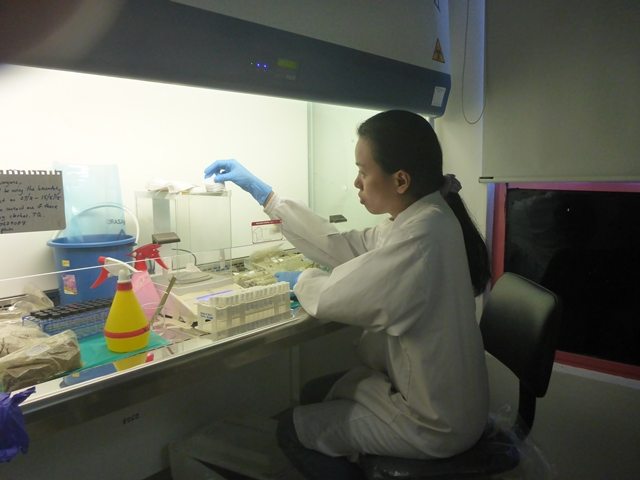

“Once we arrived back at camp, I set up a mobile laboratory so that I could extract the stress hormones from the dung and load them into cartridges ready to bring back to the UK and analyse to determine if the confined elephants have different hormone responses compared to a population of elephants that are not fenced.

Mobile lab at camp to extract the hormones and load into cartridges ready to analyse in the UK

Mobile lab at camp to extract the hormones and load into cartridges ready to analyse in the UK

“My three months in Kenya went very quickly and I am looking forward to my next field season when I will be returning in 2017 to collect more data from the elephants in the Aberdares, until then, I will be collating and analysing my results so far and continuing my work looking at the vegetation and habitat of the park using satellite imagery.”

Chester Zoo conservation scholar, Johnathan Haycock, is currently studying the immune system for the Asian elephant in order to help find a way to control the devastating effects of EEHV. Below he tells us more:

“I graduated as a veterinary surgeon from the Royal Veterinary College (RVC), London in 2011 having also studied for a degree in Veterinary Biosciences. I completed several overseas zoological placements both during and after graduation, including Singapore Zoo and Kuala Lumpur Zoo and started work at a practice in Kent dealing with both zoo and wildlife species. I returned to the RVC in 2013 to further my education in wildlife conservation and complete an MSc degree in Wild Animal Health.

“My passion for conservation of wildlife species has driven my undergraduate and masters’ theses to study elephant endotheliotropic herpesviruses (EEHVs), a group of deadly viruses affecting juvenile Asian elephants.

Almost every mammal species carries at least one herpes virus, safely hidden in their body without any apparent signs of disease except in certain circumstances, such as stress or a weakened immune system. However, EEHVs are unique in that they can cause sudden death in healthy young elephants.

“Although research supported by UK zoos has helped to improve our understanding of the viruses in recent years, we still know very little about why the viruses cause such a fatal disease and how we can help elephants to fight it.

“I continued my work in elephant conservation by volunteering at the main EEHV research centre in the UK, the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) in Weybridge, Surrey. In July 2016, I started my PhD at the APHA, funded through the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria Elephant Taxon Advisory Group (Chester Zoo, Zoological Society of London and Woburn Safari Park).

“My PhD project will focus on creating a better understanding of the Asian elephant immune system in order to help the elephants control the disease more effectively. I am specifically investigating the potential anti-viral role of interferons (a molecule produced by white blood cells to fight viral infections) and immunoglobulins (antibodies). By drawing on human medical knowledge and a new grasp of the elephant immune system, I hope to uncover ways to help prevent further fatal cases.”

We’re part of the global conservation community committed to the conservation of Asian elephants, so we will continue to carry out intensive research and work to discover more about this virus and how to treat it. Together we can find a solution!

Learn more about the viruses, the research and how to help in the fight against EEHVs here.

Join the fight now and 100% of your money will support invaluable research and help us put a stop to this devastating virus.