Tag: Championing ecological research

“Danilo Kluyber, Project Veterinarian, and Gabriel Massocato, Project Biologist, led two expeditions in both June and July in the Pantanal with two volunteers on both occasions. Then in August, I led an expedition with Gabriel, Camila Luba, a Veterinarian and Reproductive Specialist, as well as a volunteer.

“Incredibly, the team that went in June were unable to cross the floodplain with the truck and had to wade across instead. This meant that several of the animals had not been monitored since January. It was only in July that they were able to cross but even then, they had to leave the truck on the other side to avoid crossing the floodplain too many times. This is the first time in seven years that we have had to wait so long to cross the floodplain.

“Overall, all the animals are doing well but unfortunately we were not able to locate all of them. The batteries ran out of the transmitter from Liana, an adult female giant armadillo that we first monitored in 2012 and then again in 2015. Emmeline, a female giant armadillo captured in December, was very closely monitored these past few months as camera traps had shown in January that she had a 4-6 month old baby with her. However, there was no evidence of the baby anymore so we believed it died sometime between January and June. As for Tim and Isabelle, two adults giant armadillos, despite our searches there was no sign of them. Researching giant armadillos is a game of patience!

“Eric, Mafalda, Renee, Emanuel, Caetano and Tex are all doing great and they all have been fitted with a GPS Tags. Emanuel had a deep hole in his foot when he was first caught in December but in August when he was recaptured we could hardly find a scar!

“We then had another expedition in September coordinated by Gabriel along with Danilo and Debora Yogui, project veterinarian. These past two months have been incredibly hot and dry and in September fires broke out in neighboring ranches. Large areas were burnt and the landscapes became desolate in many areas but none of the animals we’ve been monitoring have died.

“The highlight of the trip was the capture of a beautiful new adult giant armadillo that the team named Amanda. She is a very healthy, huge and gentle adult and is occupying an area that we know Wally, a male we monitored two years ago, uses as well.

“The next expedition we ran in October consisted of Danilo, Nina Attias, a Brazilian biologist doing a postdoc with us and me. As Danilo and I climbed on the back of the truck and set our receptors, they started beeping. Without having moved we heard the beep we spent days searching for, which meant that Emanuel was only 300m from us! However, it still took us four nights to be able to capture him and fit him with a GPS.

“Two ranches away from Baia das Pedras, a large forested area is being converted to pasture meaning that everything is being removed, burnt, and flattened. We must however accept and understand these changes in the landscape. The owner bought this land a few years ago and needs to increase the area of pasture to sustain the ranch. This is all legal and is part of the changes the Pantanal is slowly undergoing. The owner has always been very welcoming of the project and happy to know we work in the area. Unfortunately, the area being destroyed was where our male Caetano lived so he crossed and swam across the floodplain to an area without machines, noise and fires.

“We are also involved in a corridor initiative and are starting talks for our data to be used in a Cerrado restoration initiative. This data on giant armadillos is unique and no other species in the state has such detailed distribution information!

“Giant armadillos are now being used as a flagship species for biodiversity conservation in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul. A species few people knew about only a few years ago is now influencing habitat conservation measures! We could not be happier!”

Chester Zoo has been supporting the fish ark in Morelia, Mexico since 1996, long before starting work at the zoo in 2014 I had been aware of the work of Omar Dominquez and his team within the field of Goodeid conservation.

Goodeids are a subfamily of fish comprising of 41 species, almost all are endemic to the mountainous volcanic central state of Michoacan, several of the species are already extinct in the wild and many more are threatened by various factors including pollution and introduced species out-competing them for food, space and often predating on the Goodeid offspring.

When I was told that I would be visiting Morelia to see the work first hand, as a ‘Fish geek’ my excitement could hardly be contained! To visit a beautiful country to fish for species I had often read about in books and to represent Chester Zoo at the same time – it was almost a dream come true. I travelled with my colleague and fellow aquarist Nadia Jogee (read Nadia’s blog here).

Day 1

After arriving in Morelia late in the evening, our first full day was spent acclimatising ourselves to the beautiful city of Morelia. We enjoyed watching the relaxed Mexican way of life and the way Mexican people use these open public spaces for socialising and relaxing with family and friends.

Day 2

Today we were to visit the University and Aqua lab for the first time, the team at the aqualab consists of several departments and we met and worked alongside many people, including aquatic technicians, parasitologists and limnologists.

Day 3

We travelled back to the aqua lab to meet team leader Omar Dominquez and Rodolfo Perez Rodriguez. Omar had just returned from a field trip to the Gulf of Mexico where he was collecting marine fish from an offshore reef, he was extremely welcoming and gave us an overview of the tequila splitfin (Zoogoneticus tequila) project. He then invited us to accompany him to the university’s botanical department. Here the aqualab have two semi natural ponds which are filled with three species each.

Within the pool containing tequila splitfin several hard working students were busy setting fish traps and were collecting and sorting over 700 individuals of tequila splitfin to take back to the aqualab, undergo a period of quarantine before eventually being translocated back to the Rio Teuchitlan for reintroduction. We were allowed to help with this work at the semi natural ponds.

Day 4

We were collected from our hotel at 5am and drove five hours in a North West direction to the town of Teuchitlan and the Rio Teuchitlan, the type locality for the tequila splitfin – incidentally the fish did not get its name from the alcoholic drink produced in this area, it received its name from the nearby ‘Volcán de Tequila’.

The Rio Teuchitlan is the habitat of tequila splitfin and the location of the reintroduction of the same species. It’s a short river around 1.5 miles in length, it’s source is an underground spring located in the park known as ‘El Rincon’. The site has been developed as a water park for local residents to relax and swim. The crystal clear waters are an ideal reintroduction site and the residents of Teuchitlan have a vested interest in protecting this site from pollution.

Day 5

Still in Teuchitlan we headed to ‘El Rincon’ for the second part of the project; the University team had arranged to give a presentation to the locals as part of an ongoing project. Almost all of the residents of Teuchitlan now know and recognise the university and understand the work that they’re doing in this area. The local residents are very proud to host this work and many are actively involved in protecting the environment and ensuring that ‘El Rincon’ can be enjoyed by both local bathers and the native wildlife.

The trip was a complete success! We were able to witness first-hand the work that we had read so much about in several reports, however for me the lasting impression is the shear dedication of the Mexican scientists working in the field! They work tirelessly and battle numerous obstacles to protect the goodeid species that are found exclusively in the central Mexican states.

The tequila splitfin reintroduction is nearing the end after almost five years of hard work and dedication, the first fish are now being reintroduced and only time will tell if this project is successful. The planning has been meticulous and the ground work finished, now it is time to start to think of the next project! Many other species of goodeid are critically endangered and using the knowledge gained from this project, future reintroductions will certainly be possible. None of this could be possible without the support of Chester Zoo funds and encouragement, just another reason I am SO proud to work for the zoo.

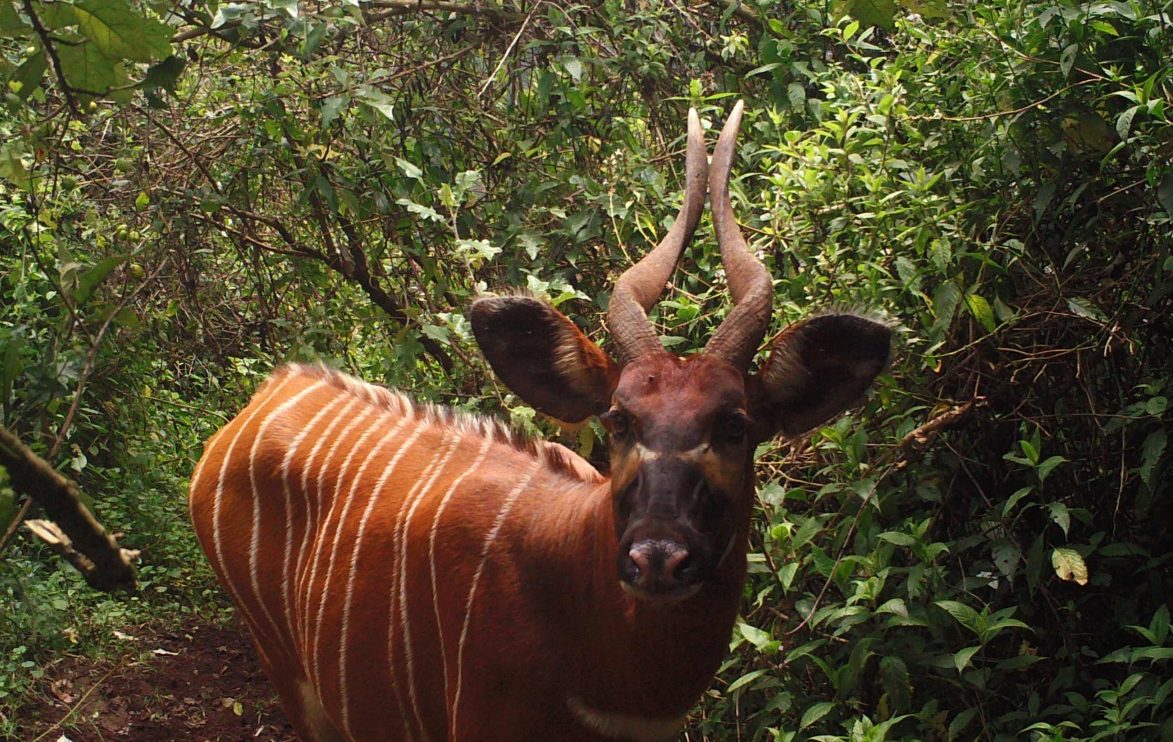

The mountain bongo, also known as the Eastern bongo, is associated with montane forests in the Kenyan highland and is known to thrive on vegetation at the edge of forests. The species is completely extinct in Uganda, and is now confined to four isolated populations located in patches of forest across Kenya. Avoiding people at all cost, this elusive species tends to end up living in unsuitable habitats in order to stay away from humans.

Tommy Sandri, a PhD student at Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU), has been studying the mountain bongo for the past four years as part of his masters and now PhD. Always interested in animals he decided a few years ago to enrol in an MSc in Zoo Conservation Biology mainly because the degree had a strong link with Chester Zoo. Below he explains more:

The mountain bongo, also known as the Eastern bongo, is associated with montane forests in the Kenyan highland and is known to thrive on vegetation at the edge of forests. The species is completely extinct in Uganda, and is now confined to four isolated populations located in patches of forest across Kenya. Avoiding people at all cost, this elusive species tends to end up living in unsuitable habitats in order to stay away from humans.

Tommy Sandri, a PhD student at Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU), has been studying the mountain bongo for the past four years as part of his masters and now PhD. Always interested in animals he decided a few years ago to enrol in an MSc in Zoo Conservation Biology mainly because the degree had a strong link with Chester Zoo. Below he explains more:

“Initially there wasn’t really a project about bongo at MMU but my supervisor Dr Edwin Harris mentioned that he had done something with that species and somehow it just clicked. I then remembered watching a Nat Geo documentary when I was younger about the bongo and how it was saved thanks to zoos’ efforts and decided to go for that project!”

Funded by Chester Zoo, Tommy started studying the habitat selection in bongos but always had the idea of looking at the genetics of the species at the back of his mind. This idea then germinated and turned into a PhD project.

Working in collaboration with the Kenyan Wildlife Service, the research team was able to place camera traps across their study area collecting crucial data on the critically endangered antelope and allowing them to obtain the first estimates of the size of the remainding bongo populations in the wild.

The Bongo Surveillance Program collected data from camera traps for more than a decade by placing their traps at strategic sites where they knew bongos to be present. However, the research in which Tommy was part of was the first to set up randomly-placed camera traps providing a robust and systematic census of the wild populations of bongos.

In addition of conducting new camera trapping activities, Tommy recently went back to Kenya to collect genetic samples from the wild bongo populations. Focusing on an area where he knew the bongos to be relatively abundant, he went looking for their dung.

“We were lucky enough to find 28 samples! One day we found an area where a herd of bongos had probably spent the morning. We know from camera traps that there should be around 12 to 16 animals there and one morning we just stumbled upon this area and under some shrubs and trees we found 16 dung piles!”

He explains that out of the 28 samples collected probably 20 will turn out to be actual bongo dung as, visually, they can easily be confused. Once the dung is collected, the researchers need to act fast to extract the DNA before it starts degrading and can then store the extracted DNA material to analyse once back in Europe.

The aim of Tommy’s study is to use micro satellites developed by MMU to investigate the genetic diversity among the four wild populations of mountain bongos found in Kenya and to then compare it to the populations kept at European zoos as part of the European Conservation Breeding Programme.

“We are going to use the studbooks to decide which individuals to sample in zoos. The main idea is to assess how related the zoos’ individuals are to the wild ones to find what might be the best lineage to start a reintroduction programme.

“One hypothesis I’ve considered is that the zoo population might actually present a higher genetic diversity than the wild ones. It might be that people took some individuals around the 1970s to send to zoos and then genetic diversity of the wild populations was lost when the numbers of animals in the wild decreased drastically.

“Knowing exactly when the zoo population was started and with how many individuals is crucial information that helps me to study their genetics. I think this project could really help to better manage the population, both wild and in zoos, and could be easily applied to other species.”

Tommy Sandri is a student from Manchester Metropolitan University and is supervised by Dr Edwin Harris, Dr Bradley Cain, Dr Martin Jones and Chester Zoo’s Deputy Curator of Mammals Dr Nick Davis. His research is funded by both Chester Zoo and Manchester Metropolitan University and is supported by the Kenyan Wildlife Service.

Our partners, the Research Center for Climate Change University of Indonesia (RCCC-UI), recently led a pilot study in several habitat types within the Bawean Wildlife Sanctuary and the Bawean Nature Reserve.

The team of researchers’ main aim was to gather baseline information about the biodiversity found on Bawean Island, as well as identify indicator species which can indicate the impact of environmental change. With this information, monitoring can start and results can be integrated into a proposed recommendation for conservation action plans.

The team on the ground conducted an inventory of some poorly-known taxonomic groups, focusing on reptiles and frogs (herpetofauna), insects including butterflies and moths (lepidoptera) and ground herbs.

Team leader, Sandy Leo, oversaw the surveying of herpetofauna and had already recognised 18 herpetofauna species (seven amphibians and eleven reptiles). The most interesting species the team found was the Malayan krait (Bungarus candidus) which was identified as the only one venomous snake on Bawean Island – which was also the top predator found, besides the Bawean serpent eagle.

Muhammad Suherman was in charge of surveying butterfly diversity on the island and to find out their population size and distribution pattern. This research was unique as many specific butterfly sub-species live in Bawean.

Muhammad focused on three families of butterflies: Nymphalidae, Papilionidae and Pieridae. The team managed to identify 41 butterfly species during the expedition and recorded several rare butterfly species such as palm kings (Amathusia phidippus), bamboo tree-browns (Lethe europa), common tigers (Danaus genutia) and the common birdwing (Troides helena) which is protected by Indonesian Government regulations but hasn’t been assessed by the IUCN Red List.

Wendy Achmmad Mustaqim and Nurrahman Fajri were in charge of the moss survey and were amazed to find very abundant epiphytic mosses on the island. Epiphytic moss grows on the surface of other plants and gets the nutrients it needs to survive from the plant it’s growing on.

Wendy explains:

Many species of mosses covered the tree trunk and also the branches. The only thing we could see around us at some point was the hanging mosses, swinging by the wind.

“We discovered that mosses decreased in abundance as we climbed the summit of Mount Lumut. It seemed to have its own world, representing a unique ecosystem on a very small range of elevation and is probably the most fragile ecosystem in Bawean!”

The team all agreed on the fact that there are still a lot of places that need to be explored on the island and lots of new species to be potentially discovered.

“More research and exploration is needed to understand how to manage this tiny island from various threats such as climate change or tourism activity.

Watch this space!

Fred Howat, Interpretation Officer, is often tasked with researching, writing, designing and installing interpretation around the zoo. These range from signage about our species to conservation projects and scientific research we’re doing at the zoo. It might also include exhibition theming, audio / visual elements and even commissioning bronze statues and artworks. However recently, he was asked to work on something slightly further afield.

Below, Fred tells us about the project that led him to Nigeria, and using his skills to support our Gashaka Biodiversity Project.

“The Gashaka Biodiversity Project (GBP) is one of our conservation projects based in Gashaka-Gumti National Park, Nigeria. Working alongside the National Parks Service, we monitor the endangered Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee, as well as study the varying ecosystems of the region using camera traps and surveys.

“As part of this project, we built an education centre on the edge of the park which serves local schools and visiting tourists. As part of my job, I was tasked with creating an exhibition for this space that could be used to teach school children about the importance of the National Park.

“My first job was to make contact with Stuart Nixon, our Field Programme Coordinator for Africa. He’s visited the park numerous times and knows the project. He was able to help me identify some key issues in the park that we could explain in the interpretation. Not only this, he put me in contact with the staff directly working in the park who I could ask more detailed questions.

“After several weeks of research and emailing, it became clear that creating an exhibition for a space I hadn’t seen was going to be quite difficult. So, soon after, it was decided I’d travel to Nigeria to see the park first hand.

“My trip to Nigeria was both my first to Africa and my first to a National Park. Flying to Abuja, the Federal Capital of Nigeria was a real eye-opener and insight into a vastly different culture. After a day’s rest, another short flight to Jalingo and four hour car ride, we arrived in Serti, a large town on the fringes of the park. This is where the Gashaka-Gumti National Parks Service is based, as well as the education centre I would be working on.

“Here we met with various staff from the park who took us to the education centre. I was able to have some good discussions about what sort of interpretation they wanted, as well as take measurements of the building and wall space. However, to really understand some of the problems faced in the park, we needed to head further in to it!

“After a two hour jeep drive, 30 minute motorbike ride and then short hike into the park, we arrived at Kwano, our research camp deep in the heart of the park. Here, we had 24 hour solar power, cooking and refrigeration facilities, a running shower (water is pumped from a local river and heated by the sun) and field assistants who maintain and manage the camp throughout the year.

“The park and camp area are beautiful, with dense forest and tall trees lining the route in. We encountered black and white colobus monkeys and some inquisitive, if not slightly intimidating olive baboons just a short distance away. It’s also not uncommon for a local troop of chimps we regularly monitor to visit either! After dumping our gear, a few hours (sweaty) hike south, following a trail of camera traps that had been set up months before, took us to a beautiful river, lined with sandy and rocky shores.

“To avoid overheating we decided to have a quick dip in the river before having lunch, all watched by another troop of baboons further down the river. Floating in the cool water, staring at the tree-lined blue sky, it was easy to forget that there was a reason we were in this beautiful forest. Beyond the treeline and further down the hill, thick black smoke was rising.

Global conservation will always rely on strong partnerships with local organisations and individuals, and nowhere is this truer than at Gashaka-Gumti National Park.

“Despite the immediate beauty of the park, it’s under huge pressure from a rapidly growing human population. Cattle grazing is the staple means of income for local people, and they roam the park in their thousands. To promote grass growth in the dry season, swathes of savannah and forest get burnt down. While this encourages new shoot to grow (and feed the cattle), it also destroys vital habitats for many species. With enough burning and cattle grazing, the forest edges close further in, shrinking what’s left of this precious ecosystem.

“And this brings us back to the interpretation. Creating an exhibition in the education centre which explains the issues is one step to saving the park. Teaching local children about the importance of saving the park also helps instil pride in their local surroundings. After several days of talking with staff, school children and teachers, I’d gained enough information and knew what I needed to do. The hard work back in the office was all to come.

“With a more environmentally friendly generation growing up, we’re hoping that they’ll take on the gauntlet of saving the park. We’ll continue playing our part, working together to protect and monitor the species found there, and to help educate the next generation of conservationists.

“Global conservation will always rely on strong partnerships with local organisations and individuals, and nowhere is this truer than at Gashaka-Gumti National Park; a place I’d be visiting again in several months’ time to install the exhibit.”

Together with the Government of Bermuda’s Department of Conservation Services and Manchester Metropolitan University, we’ve been working with Heléna to study the Bermuda skink as part of her PhD in Biodiversity Management at The University of Kent.

“I’m looking at the conservation and population status of the critically endangered Bermuda skink. There is estimated to be only 2,500 remaining in the world and their population has been in continual decline since 1965.

“The species is listed as critically endangered by the IUCN Red List and faces multiple threats on Bermuda due to several deliberate and accidental introductions of species such as rats, cats, crows, cane toads, chickens, various species of anoles, geckos, kiskadees and yellow crowned night herons. Coastal developments, invasive plants and natural disasters are other factors impacting the species and causing habitat fragmentation and destruction.

Not much is actually known about their ecology making Heléna’s work crucial to develop a better understanding of this endemic lizard species.

“Another major factor is litter being improperly discarded and washed up as marine trash in the skinks habitat. Empty bottles act as lethal traps for small insects such as woodlice or cockroaches that are attracted by the sugary fluid left inside, which in turn attracts the skinks. As the skinks have clawed feet they can’t escape and quickly die of heat exhaustion.”

The research Heléna is currently conducting is vital to find out where the skinks remain on the different islands of Bermuda but also to assess how many individuals are left in the wild and what the main threats to the species are. This information is crucial to create a plan of action for the future.

For the past few weeks, Heléna has been carrying out field surveys at four different sub-populations: Castle Island, Nonsuch Island, Southampton Island, and Spittal Pond. Taking a boat and accompanied by a team of researchers, she goes to the field sites and set up large glass jars filled with rotten sardines and cheese to attract the skinks.

She tells us more:

“I normally use 20 to 80 traps which are checked hourly during a five hour period and take genetic and faecal samples and morphometric measurements for all the individuals we manage to attract. The traps are placed 5 to 20 meters apart as skinks are thought to have a very small home range of around 10 metres. Other information such as the individuals’ stage of life, gender and missing digits or other mutilations are also recorded as they give precious information on the ecology of the species and can indicate high predation in the area.”

So far, Heléna has some interesting preliminary results indicating that skinks have not been entirely isolated on these offshore islands. It seems that some individuals living in rock crevices fall into the sea with bits of vegetation during storms and hurricanes and then drift to the next island increasing the gene flow between these vulnerable sub-populations.

Not only is this project looking at how Bermuda skinks are doing in Bermuda but it is also closely related to the work carried out at Chester Zoo. Heléna explains:

At the moment, the conservation breeding at Chester Zoo aims to improve the husbandry of Bermuda skinks for an eventual conservation breeding programme. However, once I find out where the skinks are absent or declining on the island and why, in the near future we could be reintroducing skinks back to historic sites in the wild therefore both the PhD and breeding programme are complementary elements.

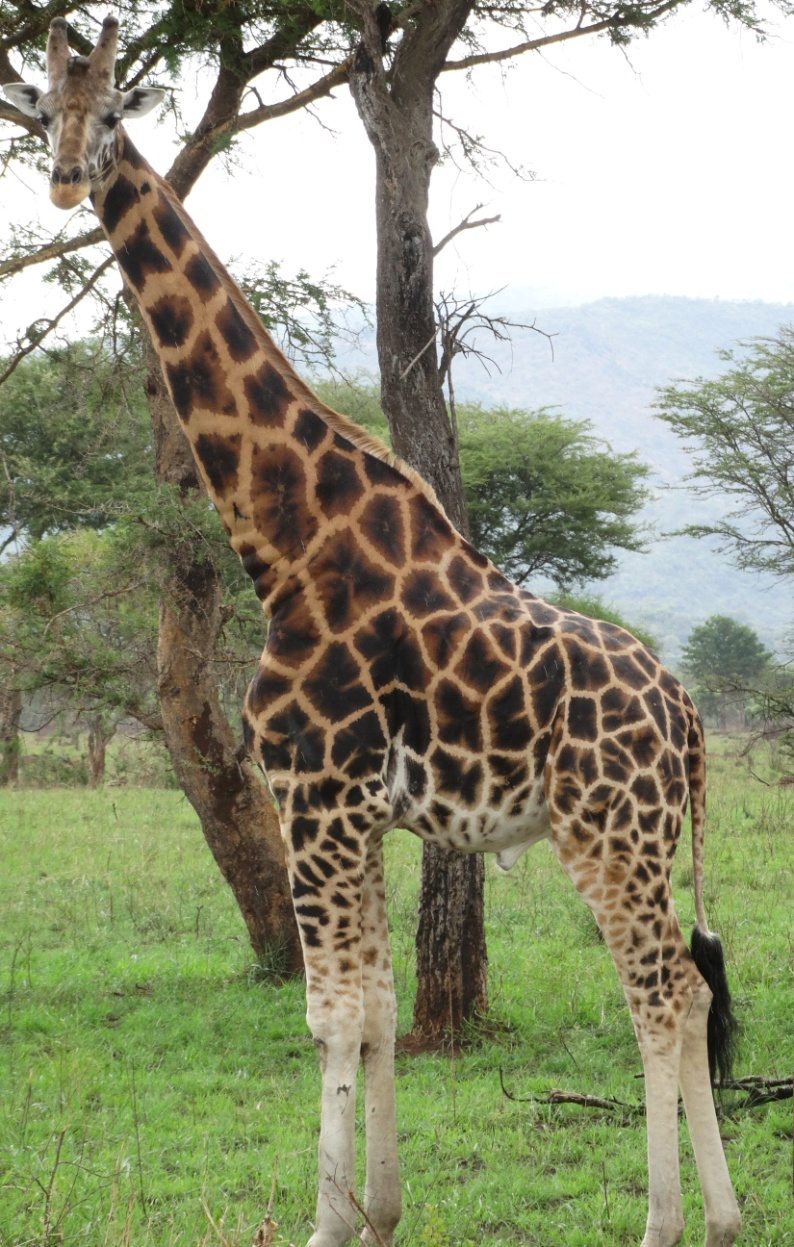

Chester Zoo giraffe keeper, Paul Round, helped to carry out this year’s census, which was led by our partners the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) and the Ugandan Wildlife Authority (UWA).

The census has revealed a steady increase in population size since 2015, with a number of new calves being identified, which is great news! The population in Kidepo Valley National Park now stands at 37 individuals.

Uganda is one of the only countries the giraffe ranges in that has seen a significant rise in population numbers over the past two decades and is a success story for the species as a whole, given the drastic overall decline of approximately 40% over the past 30 years.

Paul Round spent six days in Kidepo National Park with founder of GCF, Julian Fennessey, Michael Butler-Brown, Dartmouth College, and rangers from UWA. Each day three vehicles covered different regions of the park to survey the giraffe population, to cover as much ground as possible within the short amount of time. The team also took tissue samples from a selection of giraffes to assist with genetic analysis of the population.

This isn’t the first time we’ve provided man power and expertise to help with this important field work, led by GCF. It’s part of an ongoing project we’ve been supporting for the past two years that will make a big contribution to understanding more about this population of giraffe.

‘Unbelievable experience’

Paul tells us more about his time in the field:

“It was an unbelievable experience to go out and work with these fascinating animals in their environment and be actively involved in the conservation project with Giraffe Conservation Foundation that Chester Zoo supports. Kidepo Valley National park is a truly breath-taking National Park in the north of Uganda, with some truly stunning wildlife!”

As well as supporting vital projects in the wild, Chester Zoo is part of a successful breeding programme. Two giraffes born at the zoo, Kidepo (born 2015) and Murchison (born 2016) are named after the two protected areas that support the key populations of this subspecies in Uganda. Sarah Roffe, team manager of the giraffe team at Chester Zoo, also explains:

The arrivals have given an important boost to the European-wide breeding programme for the species and have helped to highlight the huge pressures that Rothschild’s giraffes have come under in the wild, as well as help raise awareness of the ever-growing need for conservation projects.

To acknowledge our continued support to GCF, one of the identified male giraffes has been named Chester, after the zoo.

We’ve recently provided a significant amount of financial support to GCF and UWA towards the development of the first ever national strategy for giraffe conservation in Uganda. Stuart Nixon, Chester Zoo’s Africa programme coordinator, is a member of the IUCN specialist group for giraffe and okapi and is currently in Uganda as a participant in an important meeting that aims to develop a long-term conservation strategy for these threatened animals.

In collaboration with a variety of academic institutions we support research students. These Chester Zoo conservation scholars are working to provide evidence on a range of topics, both here at the zoo and in the field.

One of our conservation scholars, Nick Harvey, has just started his PhD studying the conservation of large herbivores. The main focus of his research is the eastern black rhino, and how methods of hormone monitoring that were developed here at Chester Zoo can be used to help wild populations in Kenya grow. Alongside this, he is also interested in the aims of large herbivore conservation, what the goals are and how to work towards achieving them successfully.

Here Nick tells us more about his research below and how he needs your support with his PhD:

“Some of the world’s most spectacular species are the mega-herbivores; these are herbivores that weigh over 1000kg. At Chester Zoo the mega-herbivores that we’re working to save from extinction include black rhinos, Indian one-horned rhinos and Asian elephants. All have suffered drastic population declines in recent decades, mainly due to the current poaching crisis.

“Here at the zoo we are carrying out research to help ensure the survival of these amazing species, and we need your help! As a supporter of Chester Zoo, it’s people like you who are the driving force behind conservation, so we want to know your thoughts on the conservation of these incredible giants.

“Below is a link to a survey I’ve designed as part of my scientific research, so you can give your views on this subject and your opinion on the role of zoos in conservation.

“There are no right or wrong answers to the questions; we are looking for your honest opinions. Your response to this is completely anonymous; your name will not be attached to your survey. The last page requests a few details about yourself and will help in our analysis, but are optional for you to fill in.

“We will be sharing this survey with those working in conservation too and all the answers I receive will be analysed and used as part of my PhD with The University of Manchester, which Chester Zoo is supporting. They will also potentially be written up into a paper published in a scientific journal. So by completing the survey you can directly contribute to the conservation of rhinos and elephants! Thanks in advance for your time – I look forward to sharing updates with you as my research develops.”

You can download a Participant Information Sheet here which will provide you with more information about the survey, what the data will be used for and who to contact if you have any questions.

Scott Wilson, Chester Zoo’s head of field programmes at Chester Zoo, explains:

“Madagascar has a large amount of endemic species but they are facing a massive amount of threats such as huge areas of forest being destroyed, hunting for bushmeat (especially affecting the lemurs), but also deforestation and pet trade in the case of the golden mantella frogs which we are working hard to protect. It’s recognised internationally as a biodiversity hotspot and it’s an area where we have very strong network and have a great partner: Madagasikara Voakajy.”

You can find a number of Madagascan species at Chester Zoo, like the striking golden mantella and lemurs, which we’re also fighting to protect in the field with our partners, Madagasikara Voakajy. The local NGO has been working on the front line of conservation for years and has developed a range of projects studying diverse species such as baobab trees, fruit bats, chameleons, frogs and fish, among others.

One of the projects we’re heavily involved is protecting the tiny, colourful frog: the golden mantella. Gerardo Garcia, curator of lower vertebrates & invertebrates at Chester Zoo, tells us more:

“The golden mantella is a flagship species for amphibian conservation in Madagascar. It’s very charismatic and also the most common and attractive amphibian in the pet trade in Madagascar. It’s an animal that is very colourful, very active, small, so it ticks a lot of boxes to become a popular pet and it’s been on the trade for a long time.”

Monitoring populations

The trade of these endemic animals is legal and regulated by CITES, however, the number of individuals left in the wild has not yet been thoroughly estimated. We’re working with Madagasikara Voakaji to monitor the populations and obtain some estimates of both populations’ density and dynamics.

Having monitored the species in different ponds for years, Madagasikara Voakaji developed a monitoring programme of presence and absence of the frogs in 100 different breeding ponds allowing them to get an idea of the dynamics of the different populations but not an actual estimate of the population size. To get this number, a new study was designed, by injecting fluorescent colour under the frogs’ skins using capture-mark-recapture, and scientists were able to identify and monitor different groups of frogs.

Visiting four ponds three times over a year in 2015, the team collected a robust data-set and decided to repeat the survey a second year to strengthen the estimates and the results are currently being analysed by the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology at Kent University to gain an estimation of the population size in these ponds.

Madagasikara Voakajy has also been successful in getting the area, where we’re carrying out this vital research, recognised as a protected area – protecting 68% of the known breeding ponds for the species. This means that there are now a set of guidelines and rules for the local communities that use this area of the forest, preventing further defrestation, etc. These communities are now working with Madagasikara Voakajy and take an active role in the protection of the threatened species by patrolling for illegal gold mining activities and helping to collect data themselves.

There are other actions that could be considered to help protect the species in the long term, including building corridors to connect golden mantella populations and also restoring historical ponds that have been damaged by previous mining activities. Technology could become an important tool in monitoring the species using drones and call recorders to assess the progress of restoring the area.

Obviously there are other species living there, like lemurs! And they are not excluded from the impact of the unsustainable or illegal use of natural resources.

There are 111 different types of lemur found in Madagascar; 93 of which are assessed as threatened (either vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered by the IUCN Red List). Key actions are needed to protect this endemic animal and is the reason we’ve started a new lemur survey project! With at least nine species present in the Mangabe protected area, it is essential to take action as habitat destruction and hunting for bushmeat are still important issues in the area.

Madagasikara Voakajy have been working on a project, Youth for Lemurs, Lemurs for Youths project since 2015, that aims to build a network of young lemur conservation ambassadors within the protected Mangabe area. This is done through trainings on improved agricultural and farming techniques and also through communicating the link between implementing these techniques, conserving lemurs and improving their livelihoods.

Our ultimate goal is to stop lemur hunting by 2020!

Our new lemur survey project will assess the distribution and population numbers of the large diurnal (active during the day) lemur species and will use this data to evaluate the success of the Youth for Lemurs, Lemurs for Youths project. Threats from hunting are currently being assessed throughout the dry season and then 60 monitoring plots will be surveyed up to six times during the wet season. The whole process will be repeated each year for three years to build up information on the distribution, population of lemurs and threats within the Mangabe protected area and assess.

Watch this space for more updates from Madagascar and the projects we’re working on in this unique region.

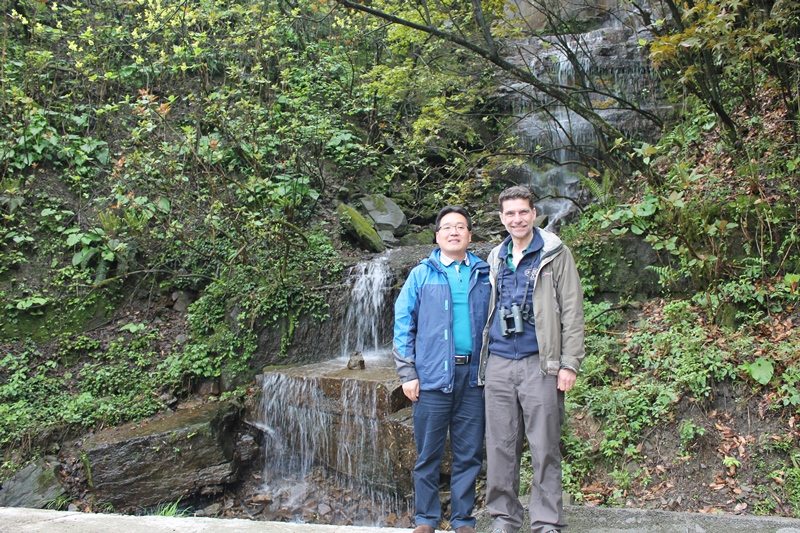

We’ve been working with the Laojunshan nature reserve in Pingshan, China since it established over 15 years ago, and Chester Zoo’s science director, Dr Simon Dowell has been involved in the project since the start.

Below he tells us more about his latest trip to China and how the project is developing:

“When we started this project, Laojunshan was established as the first local nature reserve in the region to protect endemic forest birds including the highly endangered Sichuan partridge. There was very little funding for conservation in those days and the small team of people who were expected to protect and manage the site had almost no experience or expertise.

Chester Zoo’s support was vital in providing training in biodiversity survey and monitoring, wildlife law enforcement and use of technology to facilitate management. In time we were also able to support community projects, public awareness campaigns and education work that has raised awareness amongst the local population and reduced damage from unsustainable activities like wood cutting and medicinal plant collection.

“Through our partnership and the dedication of a growing reserve management team under the skillful leadership of reserve director, Benping Chen, the reserve was promoted to provincial and then national nature reserve status.

“My recent visit revealed just how far it has come with new forest ranger stations, effective surveillance to prevent illegal activity in the reserve and a comprehensive system of wildlife monitoring through transect surveys and camera traps.

“This year is the tenth year of our annual surveys for galliformes (ground-feeding birds) in the reserve and they are showing increases in a number of key species, including the Sichuan partridge and other species like the beautiful silver pheasant, one of which we were lucky enough to see while trekking in the reserve.

“A number of Chinese universities are engaged in detailed research on birds in the reserve, including an interesting study on the songs and calls of the Emei shan liocichla, a globally threatened endemic passerine that we have been successful in breeding at Chester Zoo but which relies on reserves like Laojunshan for its continued survival in the wild.

“Under Benping Chen’s leadership, Laojunshan is now regarded as one of the best bird reserves in China and held up as a model for others to follow in terms of its protection and management. I am immensely proud of what has been achieved and of the part that Chester Zoo has been able to play through our partnership and support.”

As well as Laojunshan, Simon also visited the newest of the five reserves that we have supported; Qincaiping nature reserve in the neighbouring Muchuan county where the presence of the Sichuan partridge has recently been confirmed from footage from one of the camera traps funded by this project.

This reserve is protecting an important strip of broadleaf forest providing a habitat corridor for birds, plants and other wildlife that links Laojunshan with larger forest patches further west. Our support for the team at the nature reserve has already enabled them to establish galliforme monitoring transects and undertake essential survey and monitoring work.

Simon also attended a meeting of all the managers of the nature reserves that we have supported through this project to hear about progress and discuss future directions for the project.