Tag: Protecting animal populations

The tequila splitfin, a small species of goodied fish which grows to just 70mm in length, disappeared from the wild completely in 2003 due to pollution and the introduction of invasive, exotic fish species in waters where it had previously thrived.

‘Miss Piggy’ (officially known by the less fun, but more practical, PM07), was first translocated to Wales in mid-September of 2015. It’s been a busy three years for the Pine Marten Recovery Project team since then, and whilst we can’t have favourite martens, Miss Piggy is definitely the one that has made herself the most memorable.

She received her unusual name as she was been driven down from Scotland. Every three hours the van transporting the martens stops to offer them water and blueberries and whilst some of the animals can be very wary of people and will only eat once you have left, Miss Piggy showed no such qualms! She snaffled everything she was offered and didn’t seem at all bothered by her strange surroundings.

Once in her release pen she turned out to be very well named as most of our animals would have a period where they would hide in their box and would wait until they had the cover of darkness to come out and explore their pen and eat the food. Miss Piggy had no such reservations and was out and about within a few hours hunting out all the tasty treats we had left in her pen.

Once released she was the marten we could most regularly radio track and get on remote camera. If the team were having a bad night and all the martens had seemingly disappeared we would go to Miss Piggy’s territory as she was so reliable she would always be there to raise morale.

We didn’t expect her to breed that first spring after she was released as she was a very young animal and we suspected she wasn’t mature enough to have mated the previous summer in Scotland. After her collar was removed we monitored her via cameras sporadically as we kept a close track of the other females who were about to give birth.

Throughout the summer, during the mating season, she was caught on camera with PM17, the big male that overlapped her territory, several times. This made us hope that she had mated and would give birth to some little piggies the following spring. In May 2017, we littered her territory with cameras and hair tubes and checked all the den boxes eager to find out if she had given birth.

Unfortunately, all our efforts were in vain as she didn’t seem to settle into one maternity den site and we never had any confirmation of kits. It could be that she never actually mated, or that potentially the second tranche of releases disrupted the territories briefly or even that she did give birth to a litter but that they did not survive. Pine martens have a very high mortality as kits, with on average 50% not surviving to adulthood.

That summer, we again captured her on camera with PM17, but in May this year we were again disappointed when we checked denboxes there were no kits. The only intriguing evidence was a den box that was piled high with scats.

We monitored her cameras sporadically throughout the summer, but were convinced she hadn’t bred again until last month when we had to move a camera due to active forestry work!

We set it up in a new spot up the river from her normal territory where we had spotted some scats on the footpath. We baited the site and within a week had Miss Piggy turn up on camera. She’d do anything for some free peanuts!

We continued to check the camera throughout the month until one day we had a pine marten turn up who looked smaller, clumsier and generally different to Miss Piggy. What followed was then clip after clip of two pine martens together on camera, which is very unusual for this solitary species.

Our immediate thought was that these two were littermates from this year and so we deployed a jiggler, which is a tea strainer filled with peanut butter on a flexible wire that causes the martens to ‘meerkat’ up toward it, giving us a perfect photo of their unique bibs. This showed that indeed these two martens were new unknown martens and when they turned up on camera with Miss Piggy later in the month we knew they must be her offspring from earlier that year.

Hurray! The team were all thrilled. It is, of course, a celebration whenever we confirm any kits but these two felt especially important. Miss Piggy has been so closely followed by ourselves and Chester Zoo that it was very special to confirm that she has been contributing to the continuation of her species. K(07)1 and K(07)2 seem to share their mother’s love of food and regularly turn up on this camera so should be easy to keep track of over the next few years, until hopefully, they have their own offspring. That is a long way off though, so until then it just makes us happy to think of these three little piggies roaming about the Celtic forests.”

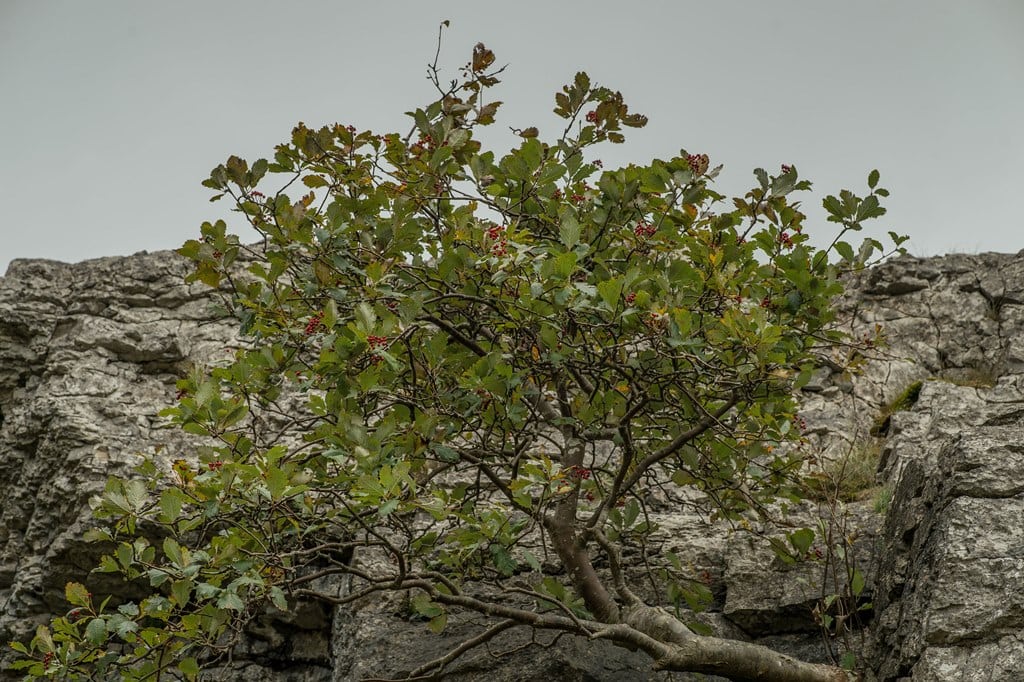

For over 200 years, botanists have known about a strange tree growing at Castell Dinas Bran near Llangollen. The plant first described in Hudson’s Flora Anglica in 1798 was recorded to be growing out of the castle walls and looked a bit like a whitebeam. Botanists were confused about what it might be and gave it several different names!

A descendant of that tree was removed from the castle in the 1990s to prevent damage to the historic castle walls. The rescued tree was planted in a private garden and almost forgotten until 2016 when we became involved. We undertook a rescue project to remove the tree from the garden and brought it back to Chester Zoo where the idea for a conservation project grew.

Endemic to the limestone crags of the Eglywyseg escarpment in Denbighshire, the Llangollen whitebeam is an extremely rare tree which before our project was carried out had an estimated total population of 250 individuals. The last survey for the species had been done in the 1980s and our experts decided it was about time to conduct a resurvey to better understand the conservation status of this special tree and assess if any action was needed to ensure the survival of the rare species.

Sarah Bird, Biodiversity Officer – UK and Europe explains:

“Having a rare endemic tree growing so close to the zoo is really exciting. With only around 250 Llangollen whitebeam trees existing anywhere in the world, this is one of the rarest species Chester Zoo works with. Botanists Tim Rich and Libby Houston, who are whitebeam experts, came to record all the trees on the crags. The Llangollen whitebeam is very similar to some other British whitebeams so we had to get the best people to do the survey.”

The full survey took place in 2017 and the team actually found 300 trees, showing that the population appears to be stable despite some threats from the invasive and non-native Cotoneaster species. Our work has resulted in an update of the species’ IUCN Red List status and measures have been taken to tackle the Cotoneaster.

In parallel with the field work, the Horticulture and Botany team at the zoo have been busy propagating Llangollen whitebeams. We have used seeds from the Millenium Seed bank at Kew and some collected from the crags, and we are thrilled to have 50 young trees in cultivation at the zoo!

Richard Hewitt, Team Manager Nursery adds:

“It is great that the nursery team are using their expertise in propagation and growing on of locally threatened native trees here at Chester Zoo. Our aim is to grow on 100 trees of Llangollen whitebeam. When they are large enough, some will be planted near Castell Dinas Bran and the rest will go into public gardens in the region where we can tell people about this incredibly rare tree.”

The project is now focussing on raising awareness of this rare species in the local area. A few of the young trees will be returned to a safe spot near castle Dinas Bran. We will also be providing specimens for local public gardens accompanied with signs explaining the importance and curious history of the tree.

The limestone cliffs where this tree grows are really amazing. You can see them and meet botanist Tim Rich in the short film here.

Rhiannon Bolton, student from the University of Liverpool, tells us more about her work at Chester Zoo below:

“The only thing I thought I was ever going to do was work in animal wellbeing and conservation. I completed a Masters degree in conservation related veterinary science and endocrinology (the study of hormones) and I was then lucky enough to become a Chester Zoo Conservation Scholar. My PhD combines all my favourite things which are animal wellbeing, conservation and endocrinology; and will hopefully enable me to make a difference!

“My main focus is on cooperatively breeding mammals, a breeding system whereby other individuals in addition to the parents help to raise the offspring. Often, only one alpha female and one alpha male will reproduce but other family members are expected and needed to help with raising the next generation. This phenomenon only occurs in about 3% of mammal species, making them absolutely fascinating. Unfortunately, many of these incredible mammal species are threatened with extinction and some are so rare that conservation breeding is now a really important safety net to ensure their survival in the long run.

“The African painted dog is one of these species and I have the chance to study it for my research. Their Latin name Lycon pictus means ‘painted wolf’ – highlighting their beautiful coat patterns. They may look a lot like the domestic dogs we have at home but three million years of evolution in a slightly different direction have resulted in them only having four toes on their front feet instead of the normal five found on dogs. Sadly painted dogs are listed as Endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and they are known to be one of the world’s most threatened carnivores. Much of their continuous decline is due to human activity and there are now less than 1,500 mature painted dogs left in the wild. We, therefore, have a responsibility to do something about it!

“In addition to the conservation work Chester Zoo contributes to in the Mkomazi Game Reserve in Tanzania, a stable global ex situ population of painted dogs is needed to prevent the species’ extinction. In their natural habitat painted dogs live in large packs of around 20 adults and have a large home range. They work together to hunt for prey and the pack assist the breeding pair to rear pups. Painted dogs compete for dominance status to breed and the young leave their natal packs around two years of age. Due to their natural family dynamics and large home range, painted dogs can be challenging to breed in ex situ conditions and aggression can occur when the pack is establishing who will be the breeding pair. If we can determine which factors cause heightened aggression in ex situ populations, we may be able to identify practical solutions to improve breeding success and minimise aggression.

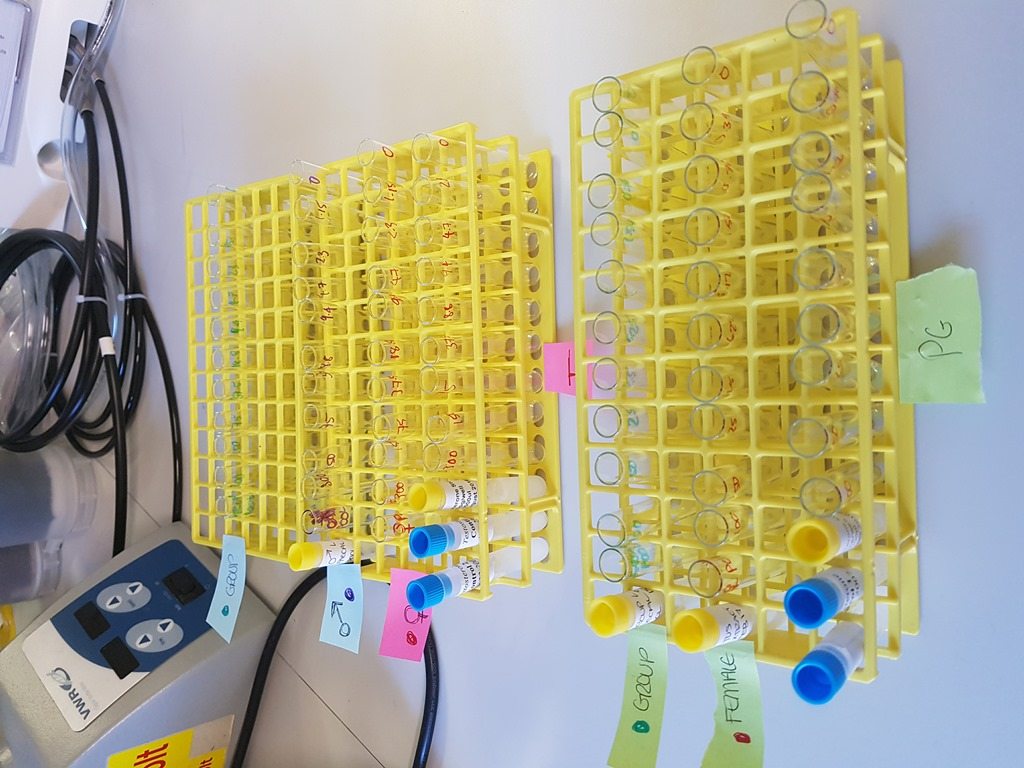

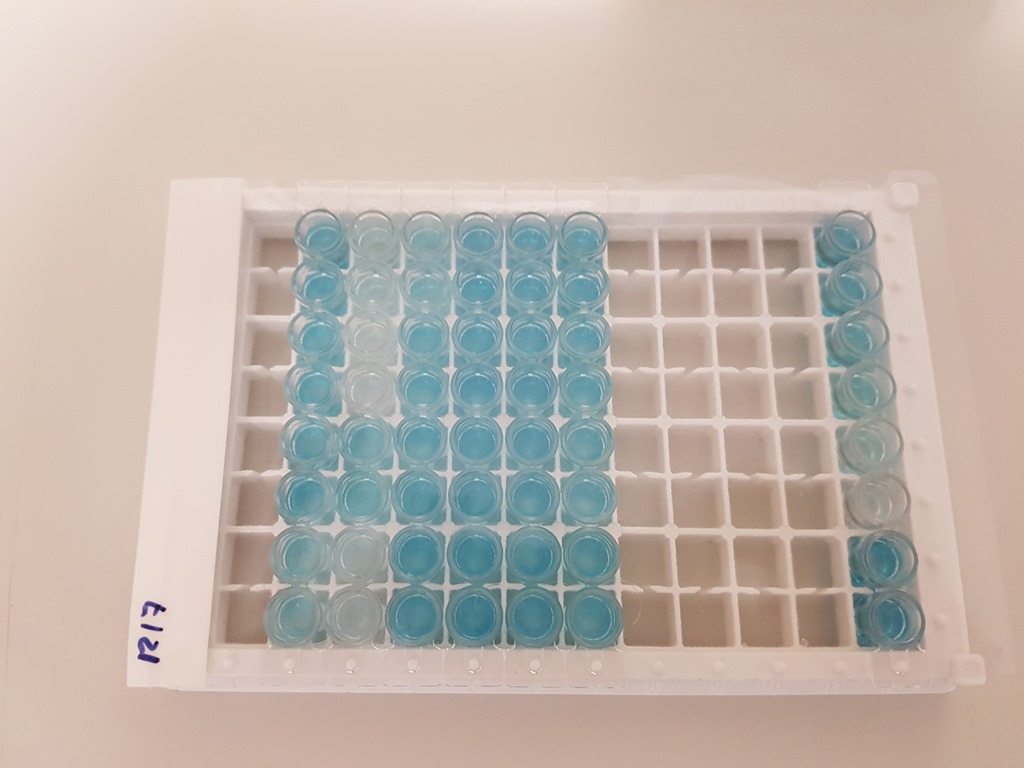

“I am approaching this challenge from three different angles: at the University of Liverpool I work with wild house mice, another mammal that shares parental responsibilities. The mice breed in semi-naturalistic conditions and I can see if maternal influences or the post-natal environment can influence mouse behaviour when they grow into adults. Although these controlled conditions are impossible to replicate in endangered species management, the results should provide an understanding of which factors are important in influencing behaviour allowing these to be focused on in ex situ populations. In addition to behavioural studies, I also look at the physiology behind the varying behaviours using non-invasive samples such as urine and faeces.

“In parallel, I have been following the painted dog pack here at Chester Zoo. I have conducted behavioural observations from when the pack first arrived at the zoo and were introduced to each other to over two breeding seasons with all the highs and lows of sibling rivalry. At the same time, faecal samples were collected for hormonal analysis. By combining hormonal and behavioural data our aim is to identify a specific trigger that can be used to predict outbreaks of future aggression.

“As part of my PhD, I am also working with the painted dog studbook keeper and European Taxon Advisory Group (TAG) for canines to widen my study to the European zoo population of painted dogs. We have designed a questionnaire to gather more information about behaviour and breeding success which will not only increase the sample size of my study but also enable us to look further into which factors promote cooperation and good breeding success within this species.

“The great thing about working with the TAG means that our research findings can have an impact not just on the dogs studied here but could influence the reproductive success of breeding packs across Europe! We have already had a number of positive responses from various zoos who work with the species which highlights the importance of this work.

“As well as hoping to make a difference to animal welfare and improve conservation breeding, this research project allows me to work with many incredible experts. Half of the time I work with the amazingly knowledgeable Mammalian Behaviour and Evolution Group at the University of Liverpool, and the other half, I’m working with Chester Zoo’s Applied Science team. I’ve also had the opportunity to work with keeping staff, vets and members of the wider zoo community across Europe. All are extremely professional and dedicated to their work in improving the wellbeing of animals at the zoo and to the greater goal of conservation.

“In the future, I hope the knowledge I have obtained during this research can be used as an insight to improve fertility and wellbeing of other endangered animals.”

Rhiannon Bolton is a NERC funded PhD student on the Adapting to the Challenges of a Changing Environment Doctoral Training Programme from the University of Liverpool. Rhiannon is supervised by Professor Paula Stockley, Professor Jane Hurst, Dr Lisa Holmes and Dr Sue Walker.

Chester Zoo first started working with the endangered Ecuador Amazon parrot back in the 1980s when a collection of individuals were confiscated at customs and distributed to a number of zoos across Europe to be cared for. Since then, they have become part of an Endangered Breeding Programme, which is managed by Chester Zoo.

The Chester Zoo team have been working in Ecuador to assess the current population of the parrots, as well as their habitat. They’ve also been hard at work installing nest boxes and working with the local community to increase their understanding of the parrots’ behaviour.

Our project partners, Fundación Pro-Bosque, are based in the dry forests of the Cerro Blanco, running assessments and also protecting the forest from fires, hunters and other threats to the ecosystem. We’re also working with local independent biologists with invaluable knowledge of the area and the animals.

Watch the video below to find out all about our conservation work in Ecuador, why the Ecuador Amazon parrot is important, and how you can get involved to save them.

We work in 80 countries across the globe to help some of the world’s most endangered animals. Working closely with many organisations we provide both funding and expertise to help the fate of species which are on the edge of extinction.

The Mauritian Wildlife Foundation (MWF) is one of the organisations we work with, helping conserve some of the endangered endemic plant and animal species of the Mascarene islands of Reunion, Mauritius and Rodrigues. These islands are located 700 km east of Madagascar. Back in the 16th century, the first settlers arrived – soon after the last dodo was killed by sailors. Many other species succumbed to the same fate and with introduction of alien species, many native species’ habitats disappeared. Today, the islands have lost most of their native vegetation and the growing human population has put increased pressure on remaining forest fragments. However, over the years some species numbers have increased including the once nearly extinct Rodrigues fruit bat.

Chester Zoo’s Twilight Team Manager and global species co-ordinator for the Rodrigues fruit bat, David White, travelled to the islands. Here he tells us more about his trip:

“The Rodrigues fruit bat was once described as ‘the rarest bat in the world’. In the 1970s the species almost went extinct as numbers dropped to just 70 bats. However ongoing conservation work and habitat protection in Mauritius – which we have supported for a number of years – together with research, education and an effective breeding programme in zoos has since seen the population steadily increase. Yet as the bats are only found in a single location on Rodrigues they are classed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature so monitoring their numbers is imperative. Therefore on my recent visit I worked with the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation to help conduct the quarterly bat counts across the island.

“One of the most breath-taking moments for me was standing at the top of the valley to Cascade Pigeon, one of the largest habitats for the bat on the island, where some 40 years before, the great conservationist Gerald Durrell had witnessed first-hand the plight of the Rodrigues fruit bat. He decided to create an insurance population, the first for this species, in the 1970s to ensure its survival. The founder animals came from the very valley that I saw before me and I now work with their ancestors in Chester.

“I love the Rodrigues fruit bat, they are also known as the Rodrigues flying fox because their elongated muzzles give them a distinctly fox-like appearance. The first time I experienced a wild Rodrigues fruit bat in flight was a little surreal: they looked so majestic and graceful. Roost sites chosen by the bats were in tall trees, situated on steep sided valleys which offered them shelter from the elements. Some of these roosts were very difficult to access due to the steep sided valley and the undulating terrain.

“To get an idea of the wild Rodrigues fruit bat population, evening dispersal counts are carried out simultaneously at each roost across the island. I took part in roost counts in three different locations. It was so peaceful, perched at the top of the cliff overlooking the valley below, bats flying past as they left the roost sites to feed. It really is vital that we succeed in our attempts to conserve this wonderful species.

“So how do you conduct a roost count? Well an imaginary line was visualised from the cliff top to a building in the distance. When a bat crossed this line it was counted as leaving the roost; any returning bats were subtracted and the count finished when it was too dark to see any bats. I had the privilege of witnessing some pups, still dependent on their mothers. It still amazes me how the female bats can fly with pups attached to them.

“During my time on Rodrigues Island, I visited the nature reserve Grande Montagne one of the last remaining strands of forest on the island. The reserve has undergone allot of restoration work to help protect the native and unique flora and fauna and the MWF has overseen the planting of over 150,000 native plant species, whilst eradicating invasive ones. The nature reserve also provide crucial habitats for the last three surviving endemic species: the Rodrigues fruit bat, Rodrigues warbler and Rodrigues Fody.

It was a privilege to lend the skills I’ve developed here in Chester to our work in the wild witness first-hand a conservation success story.

“Back in the 70’s it was believed that this species could disappear in the wild altogether but thankfully due to the perseverance of many different organisations and the start of a very successful breeding programme the number of Rodrigues fruit bat has increased dramatically. I hope that with the brilliant work we support with the MWF the numbers continue to increase and the bats will continue to thrive in their native home.”

Staying in Mauritius

Conservationists, fruit growers, netting experts and government officials gathered for the first time in a joint effort to develop new solutions to resolve conflict between farmers and crop raiding bats.

Chester Zoo has been supporting the fish ark in Morelia, Mexico since 1996, long before starting work at the zoo in 2014 I had been aware of the work of Omar Dominquez and his team within the field of Goodeid conservation.

Goodeids are a subfamily of fish comprising of 41 species, almost all are endemic to the mountainous volcanic central state of Michoacan, several of the species are already extinct in the wild and many more are threatened by various factors including pollution and introduced species out-competing them for food, space and often predating on the Goodeid offspring.

When I was told that I would be visiting Morelia to see the work first hand, as a ‘Fish geek’ my excitement could hardly be contained! To visit a beautiful country to fish for species I had often read about in books and to represent Chester Zoo at the same time – it was almost a dream come true. I travelled with my colleague and fellow aquarist Nadia Jogee (read Nadia’s blog here).

Day 1

After arriving in Morelia late in the evening, our first full day was spent acclimatising ourselves to the beautiful city of Morelia. We enjoyed watching the relaxed Mexican way of life and the way Mexican people use these open public spaces for socialising and relaxing with family and friends.

Day 2

Today we were to visit the University and Aqua lab for the first time, the team at the aqualab consists of several departments and we met and worked alongside many people, including aquatic technicians, parasitologists and limnologists.

Day 3

We travelled back to the aqua lab to meet team leader Omar Dominquez and Rodolfo Perez Rodriguez. Omar had just returned from a field trip to the Gulf of Mexico where he was collecting marine fish from an offshore reef, he was extremely welcoming and gave us an overview of the tequila splitfin (Zoogoneticus tequila) project. He then invited us to accompany him to the university’s botanical department. Here the aqualab have two semi natural ponds which are filled with three species each.

Within the pool containing tequila splitfin several hard working students were busy setting fish traps and were collecting and sorting over 700 individuals of tequila splitfin to take back to the aqualab, undergo a period of quarantine before eventually being translocated back to the Rio Teuchitlan for reintroduction. We were allowed to help with this work at the semi natural ponds.

Day 4

We were collected from our hotel at 5am and drove five hours in a North West direction to the town of Teuchitlan and the Rio Teuchitlan, the type locality for the tequila splitfin – incidentally the fish did not get its name from the alcoholic drink produced in this area, it received its name from the nearby ‘Volcán de Tequila’.

The Rio Teuchitlan is the habitat of tequila splitfin and the location of the reintroduction of the same species. It’s a short river around 1.5 miles in length, it’s source is an underground spring located in the park known as ‘El Rincon’. The site has been developed as a water park for local residents to relax and swim. The crystal clear waters are an ideal reintroduction site and the residents of Teuchitlan have a vested interest in protecting this site from pollution.

Day 5

Still in Teuchitlan we headed to ‘El Rincon’ for the second part of the project; the University team had arranged to give a presentation to the locals as part of an ongoing project. Almost all of the residents of Teuchitlan now know and recognise the university and understand the work that they’re doing in this area. The local residents are very proud to host this work and many are actively involved in protecting the environment and ensuring that ‘El Rincon’ can be enjoyed by both local bathers and the native wildlife.

The trip was a complete success! We were able to witness first-hand the work that we had read so much about in several reports, however for me the lasting impression is the shear dedication of the Mexican scientists working in the field! They work tirelessly and battle numerous obstacles to protect the goodeid species that are found exclusively in the central Mexican states.

The tequila splitfin reintroduction is nearing the end after almost five years of hard work and dedication, the first fish are now being reintroduced and only time will tell if this project is successful. The planning has been meticulous and the ground work finished, now it is time to start to think of the next project! Many other species of goodeid are critically endangered and using the knowledge gained from this project, future reintroductions will certainly be possible. None of this could be possible without the support of Chester Zoo funds and encouragement, just another reason I am SO proud to work for the zoo.

A species that used to be found in abundance across North Africa, Southern and Central Europe and the Middle East, the northern bald ibis is now classified as Critically Endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species and has been since 1994. The species is threatened by hunting, habitat loss, pesticide poisoning, powerlines and an increase in construction works around their preferred nesting sites.

The northern bald ibis has undergone a long-term decline and more than 98% of the wild population has been lost, putting the birds on the very brink of extinction. We joined the reintroduction programme ‘Proyecto Eremita’ in 2007 and have been working closely with Jerez Zoo, the Andalusian government and other conservation institutions across Europe to re-establish the species in Europe and help prevent the birds from disappearing from the wild altogether.

Mike Jordan, Collections Director at Chester Zoo, explains:

“Sadly, the species has been extinct in Europe for more than 300 years and since joining the reintroduction programme in 2007, we’ve made great efforts to breed these birds so that they can eventually go on to be released back into the wild. We hope that by reintroducing birds back into a safe, secure and monitored site in southern Spain they will hopefully go on to successfully breed and give the species a foothold once more in Europe.”

Lauren Hough, Bird Keeper, had the opportunity to travel to Jerez and got to see some of the Chester Zoo birds released from previous years. She tells us:

“I went out with the Ibis Team there in Spain and did some surveys. We were lucky enough to see two of the birds from Chester Zoo that had been released in the wild last year! Zoos from across Europe take part in the reintroduction effort sending some of their birds to Jerez were they are then released.

Conservation breeding

“It’s a cycle that repeats itself each year. In November Zoo Botánico Jerez will start receiving birds from other zoos that have been bred for the release programme. Once the birds reach Jerez they are put in quarantine for a month and are then placed in release aviaries. They spend some time there to acclimatise to their new environment and around January, depending on the weather, the gates of the aviaries open up and the birds are free to come and go for a while.

“Once the birds have fully fledged, the Spanish team can start monitoring the released individuals to get precious data on their reintroduction. To be able to monitor those birds, experts ring the individuals and microchip them allowing the local team to get a better idea of the distribution of the ibises in the wild.”

“They all have two different rings on, one is a metal ring and the other is a plastic ring with three characters on either letters or numbers and different colours so that conservationists can recognise them.”

Tipped off by a local farmer, the Ibis Team drove Lauren to a field where she had the chance to observe a flock of more than 50 ibises.

Lauren continues:

We just sat there looking at them for a bit. Then Salvador, one of the guys from the Ibis Team, put his black t-shirt and his helmet on and just started whistling slowly making his way to the group. You could tell the previously hand-reared ibises were familiar with him so they just came towards him and that’s how we managed to spot the birds’ rings and identified that two were from Chester!

Getting close to ibis

The rearing costume composed of a black t-shirt and a beaked helmet is used during the hand-rearing period to avoid imprinting on the ibises but still allowing the researchers to monitor them closely once they are released in the wild. The project has been so successful that the team is now planning on reintroducing the ibises to a secondary area in Spain that has been identified as suitable for them!

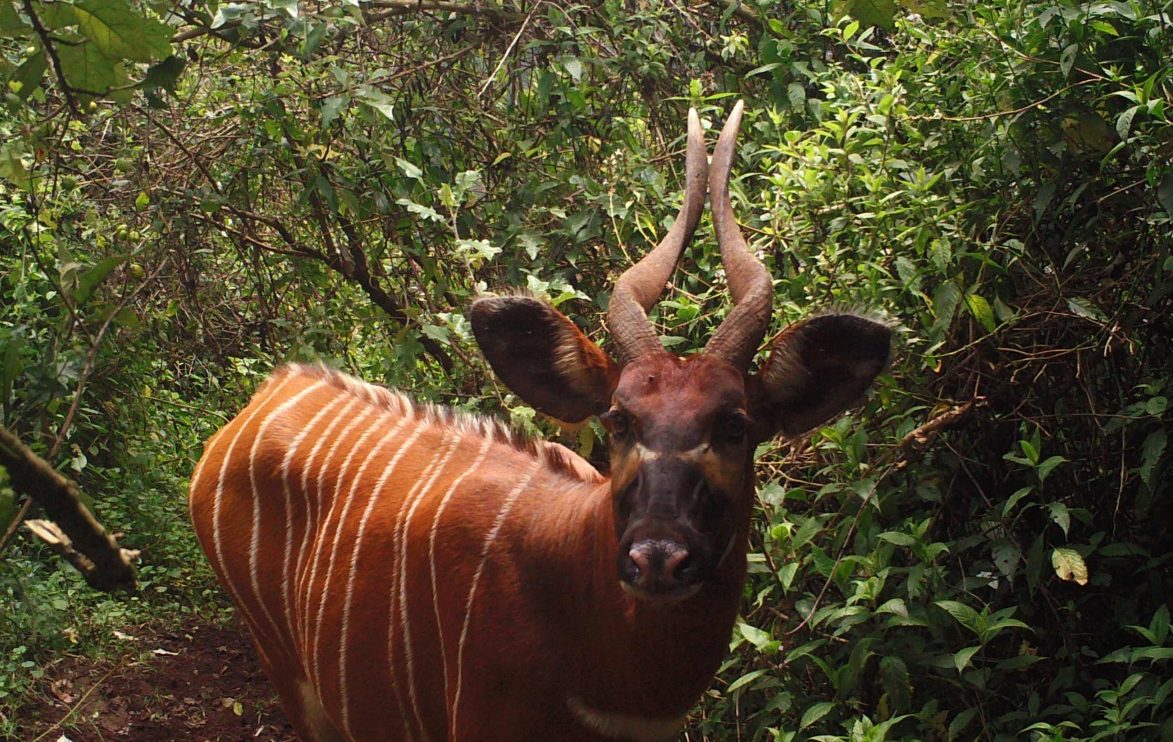

The mountain bongo, also known as the Eastern bongo, is associated with montane forests in the Kenyan highland and is known to thrive on vegetation at the edge of forests. The species is completely extinct in Uganda, and is now confined to four isolated populations located in patches of forest across Kenya. Avoiding people at all cost, this elusive species tends to end up living in unsuitable habitats in order to stay away from humans.

Tommy Sandri, a PhD student at Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU), has been studying the mountain bongo for the past four years as part of his masters and now PhD. Always interested in animals he decided a few years ago to enrol in an MSc in Zoo Conservation Biology mainly because the degree had a strong link with Chester Zoo. Below he explains more:

The mountain bongo, also known as the Eastern bongo, is associated with montane forests in the Kenyan highland and is known to thrive on vegetation at the edge of forests. The species is completely extinct in Uganda, and is now confined to four isolated populations located in patches of forest across Kenya. Avoiding people at all cost, this elusive species tends to end up living in unsuitable habitats in order to stay away from humans.

Tommy Sandri, a PhD student at Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU), has been studying the mountain bongo for the past four years as part of his masters and now PhD. Always interested in animals he decided a few years ago to enrol in an MSc in Zoo Conservation Biology mainly because the degree had a strong link with Chester Zoo. Below he explains more:

“Initially there wasn’t really a project about bongo at MMU but my supervisor Dr Edwin Harris mentioned that he had done something with that species and somehow it just clicked. I then remembered watching a Nat Geo documentary when I was younger about the bongo and how it was saved thanks to zoos’ efforts and decided to go for that project!”

Funded by Chester Zoo, Tommy started studying the habitat selection in bongos but always had the idea of looking at the genetics of the species at the back of his mind. This idea then germinated and turned into a PhD project.

Working in collaboration with the Kenyan Wildlife Service, the research team was able to place camera traps across their study area collecting crucial data on the critically endangered antelope and allowing them to obtain the first estimates of the size of the remainding bongo populations in the wild.

The Bongo Surveillance Program collected data from camera traps for more than a decade by placing their traps at strategic sites where they knew bongos to be present. However, the research in which Tommy was part of was the first to set up randomly-placed camera traps providing a robust and systematic census of the wild populations of bongos.

In addition of conducting new camera trapping activities, Tommy recently went back to Kenya to collect genetic samples from the wild bongo populations. Focusing on an area where he knew the bongos to be relatively abundant, he went looking for their dung.

“We were lucky enough to find 28 samples! One day we found an area where a herd of bongos had probably spent the morning. We know from camera traps that there should be around 12 to 16 animals there and one morning we just stumbled upon this area and under some shrubs and trees we found 16 dung piles!”

He explains that out of the 28 samples collected probably 20 will turn out to be actual bongo dung as, visually, they can easily be confused. Once the dung is collected, the researchers need to act fast to extract the DNA before it starts degrading and can then store the extracted DNA material to analyse once back in Europe.

The aim of Tommy’s study is to use micro satellites developed by MMU to investigate the genetic diversity among the four wild populations of mountain bongos found in Kenya and to then compare it to the populations kept at European zoos as part of the European Conservation Breeding Programme.

“We are going to use the studbooks to decide which individuals to sample in zoos. The main idea is to assess how related the zoos’ individuals are to the wild ones to find what might be the best lineage to start a reintroduction programme.

“One hypothesis I’ve considered is that the zoo population might actually present a higher genetic diversity than the wild ones. It might be that people took some individuals around the 1970s to send to zoos and then genetic diversity of the wild populations was lost when the numbers of animals in the wild decreased drastically.

“Knowing exactly when the zoo population was started and with how many individuals is crucial information that helps me to study their genetics. I think this project could really help to better manage the population, both wild and in zoos, and could be easily applied to other species.”

Tommy Sandri is a student from Manchester Metropolitan University and is supervised by Dr Edwin Harris, Dr Bradley Cain, Dr Martin Jones and Chester Zoo’s Deputy Curator of Mammals Dr Nick Davis. His research is funded by both Chester Zoo and Manchester Metropolitan University and is supported by the Kenyan Wildlife Service.

Together with the Government of Bermuda’s Department of Conservation Services and Manchester Metropolitan University, we’ve been working with Heléna to study the Bermuda skink as part of her PhD in Biodiversity Management at The University of Kent.

“I’m looking at the conservation and population status of the critically endangered Bermuda skink. There is estimated to be only 2,500 remaining in the world and their population has been in continual decline since 1965.

“The species is listed as critically endangered by the IUCN Red List and faces multiple threats on Bermuda due to several deliberate and accidental introductions of species such as rats, cats, crows, cane toads, chickens, various species of anoles, geckos, kiskadees and yellow crowned night herons. Coastal developments, invasive plants and natural disasters are other factors impacting the species and causing habitat fragmentation and destruction.

Not much is actually known about their ecology making Heléna’s work crucial to develop a better understanding of this endemic lizard species.

“Another major factor is litter being improperly discarded and washed up as marine trash in the skinks habitat. Empty bottles act as lethal traps for small insects such as woodlice or cockroaches that are attracted by the sugary fluid left inside, which in turn attracts the skinks. As the skinks have clawed feet they can’t escape and quickly die of heat exhaustion.”

The research Heléna is currently conducting is vital to find out where the skinks remain on the different islands of Bermuda but also to assess how many individuals are left in the wild and what the main threats to the species are. This information is crucial to create a plan of action for the future.

For the past few weeks, Heléna has been carrying out field surveys at four different sub-populations: Castle Island, Nonsuch Island, Southampton Island, and Spittal Pond. Taking a boat and accompanied by a team of researchers, she goes to the field sites and set up large glass jars filled with rotten sardines and cheese to attract the skinks.

She tells us more:

“I normally use 20 to 80 traps which are checked hourly during a five hour period and take genetic and faecal samples and morphometric measurements for all the individuals we manage to attract. The traps are placed 5 to 20 meters apart as skinks are thought to have a very small home range of around 10 metres. Other information such as the individuals’ stage of life, gender and missing digits or other mutilations are also recorded as they give precious information on the ecology of the species and can indicate high predation in the area.”

So far, Heléna has some interesting preliminary results indicating that skinks have not been entirely isolated on these offshore islands. It seems that some individuals living in rock crevices fall into the sea with bits of vegetation during storms and hurricanes and then drift to the next island increasing the gene flow between these vulnerable sub-populations.

Not only is this project looking at how Bermuda skinks are doing in Bermuda but it is also closely related to the work carried out at Chester Zoo. Heléna explains:

At the moment, the conservation breeding at Chester Zoo aims to improve the husbandry of Bermuda skinks for an eventual conservation breeding programme. However, once I find out where the skinks are absent or declining on the island and why, in the near future we could be reintroducing skinks back to historic sites in the wild therefore both the PhD and breeding programme are complementary elements.