Tag: Protecting animal populations

Oliver Hughes, Chester Zoo Conservation Scholar, is fascinated by orchids and has spent five years researching them for his MPhil and PhD. Below he tells us more about his passion for the colourful flowers and the work he’s doing to protect them:

“I’ve always been interested in nature but I particularly got interested in orchids when I started recreating different natural habitats and gardens. I discovered some amazing native plants at some point and they turned out to be orchids which I’d always associated with tropical rainforests!”

“After realising that orchids were actually present in British and European woodlands and meadows, I started growing them and became increasingly curious about different propagation techniques.

“Often colourful and exotic, orchids are well-known around the world and many species are sold as ornamental plants. However, their survival in the wild relies on a very specific interaction with fungi. Unlike most plants, orchids have seeds that need to enter into contact with a fungus to be able to develop and grow.

“The main thing is that orchids have a very specific association with fungi. They can’t actually germinate themselves without them! Orchids can produce a huge amount of seeds but they wholly rely on finding the right fungi in their environment to grow. Chester Zoo has thousands of pleurothallid orchids, so it was interesting to see the zoo’s huge collection. It has been an eye opener for me to work on their conservation!”

“My PhD focused on comparing various methods involving different media and fungi with the aim of increasing our knowledge of these species’ biology and conservation. In Central and South America, local people could make a local business out of propagating orchids in places where orchids are found naturally. So instead of chopping down the cloud forest around them or having plantations, the local communities could use orchids as a valuable resource and make more money out of propagating the plants and encouraging education projects around those emblematic species.”

With only around 650 individuals believed to remain across Africa, the two new arrivals at Chester Zoo are much welcomed additions; giving global population numbers a boost!

Chester Zoo’s Curator of Mammals, Tim Rowlands, said:

“These two births are a magnificent boost to the endangered species breeding programme and offer new hope for these wonderful animals. Eastern black rhinos are one of the world’s most high profile species, teetering on the brink of extinction in the wild; we cannot underestimate how important this is. The whole team is overjoyed and we now hope that these little ones help create more awareness of the plight of their cousins in the wild.”

The growing price of rhino horn has led to a huge decline in population numbers, which have decreased by up to 97% across Africa in the past 50 years!

The year 2014 was branded ‘the worst poaching year on record’ by leading conservationists after over 1,200 rhinos were hunted in South Africa alone – a 9,000% increase from 2007! The issue is being fuelled by the street value of rhino horn, which is currently changing hands for more per gram than both gold and cocaine, although modern science has already proven it to be completely useless for medicinal purposes as it’s made from the keratin – the same material as human hair and nails.

The in-depth specialist knowledge developed by our keeping and science teams that are running the rhino breeding programme, is being used right now in Africa to boost conservation efforts in the field.

Mike Jordan, Chester Zoo Collections Director, tells us:

“It’s superb to see the new calves taking their first steps; as we consider that each and every rhino calf is so important to the future of the species. We are one of a number of conservation organisations working in Africa – including Save the Rhino International and the International Rhino Foundation – to ensure the long-term survival of both black and white rhinoceros in the wild.

Alongside that, it’s vitally important to have a healthy breeding programme in zoos to maintain a genetically viable insurance population of the species and to develop the husbandry and scientific expertise that can be transferred to the wild. Conservation is critical, which is why these births are so vital.

We’re one of the main organisations fighting for the survival of eastern black rhino and have supported conservation efforts in the field to try and protect the species and we will continue to do all we can through funding and providing expertise, to numerous projects and sanctuaries in Africa.

The Chester Zoo Black Rhino Programme started in 1999, in partnership with Save the Rhino, providing substantial support to Kenya Wildlife Service to enable the translocation of 20 black rhinos to wildlife reserves in the Tsavo region of Kenya. The zoo has also provided support for rhinos in Chyulu Hills National Park and Laikipia District in Kenya and Mkomazi in Tanzania.

Our partners in Mkomazi have also been celebrating a new arrival after spotting a male calf within the reserve. The calf‘s mum, Daisy was also born in Mkomazi back in 2009 after a successful translocation, which means the new male calf is a second generation birth in the wild.

Two years ago the world’s leading experts on rhinos and rhino conservation came together in Europe for the first time when Chester Zoo hosted over 100 zookeepers, researchers, scientists and conservationists from the USA, Australia, Africa and Europe to debate issues surrounding the five species of rhino – black, greater one-horned, white, Sumatran and Javan rhino.

We won’t give up! We will continue to do all we can to stop the eastern black rhino from going extinct!

In 2016, scientists officially announced Bornean orangutans as ‘Critically Endangered’, making the birth at the zoo extra special. Chester Zoo plays a vital role in helping save wildlife from extinction through conservation breeding programmes; which are becoming more and more important in the survival of threatened species.

Chester Zoo’s curator of mammals, Tim Rowlands, said:

“Bornean orangutan numbers are plummeting at a frightening rate. A major threat to the survival of these magnificent creatures is the unsustainable oil palm industry which is having a devastating effect on the forests where they live. They are also the victims of habitat loss and illegal hunting.

“Those who are responsible for their decline have pushed them to the very edge of existence – and if the rate of loss continues, they could very well be extinct in the next few decades.

It’s therefore absolutely vital that we have a sustainable population of Bornean orangutans in zoos and every addition to the European Endangered Species Breeding Programme is so, so important.

“It’s also imperative that we continue to tackle the excessive deforestation in Borneo and show people everywhere that they too can make a difference to the long-term survival of orangutans. Simple everyday choices, such as making sure your product purchases from the supermarket contain only sustainably sourced palm oil, can have a massive impact.”

It has been proven that the number of Bornean orangutans will decline by about 80% between 1950 and 2025. To put that into perspective – an 80% decline is like losing four out of five people you know! Over the past 40 years, a total of 17.7million hectares of forest has been destroyed in Borneo, mainly due to make way for oil palm plantations. Half of which used to be prime orangutan habitat.

It’s predicted that a further 15 million hectares of forest will be cleared and converted to plantations by 2025! This isn’t the only threat this incredible species is facing; it’s being hunted for its meat and to stop crops from being raided.

We’ve been working with our partners, HUTAN – Kinabatangan orangutan conservation programme for over 10 years to protect the forests and wildlife of the Kinabatangan region of Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. Our partnership has grown over the years and despite the challenges that remain in the field, we continue to work hard to help make a difference.

We won’t stand back; now is the time to act for orangutans.

We’ve been working with the Big Life Foundation for over a decade to protect and monitor a population of eastern black rhinos in Chyulu Hills National Park. The black rhino is one of the most endangered species on Earth; they’re being brutally killed because of the trade in their horn. The eastern black rhino is the most endangered of all the African rhinos – only 740 remain in the wild!

Chyulu is the only population of black rhino remaining in Kenya where all the individuals are native and naturally occurring, making it a uniquely important site for rhino conservation.

Protecting these precious animals is a 24 hour job – and a dangerous one too! Poachers are often part of highly organised and armed criminal gangs and will find any way possible to get hold of rhino horn for the international illegal trade. They will stop at nothing to get their hands on it so the rangers need to be highly trained, heavily armed and very disciplined. While most rhino hunting attempts are stopped by the rangers before they can take place, five rhino have still been poached in Chyulu Hills over the past three years, which has a devastating impact on this tiny population.

The long term future of the black rhino is hanging in the balance across Africa. The team of Big Life rangers at Chyulu are absolutely vital in the fight to protect rhinos from the illegal poaching for its horn.

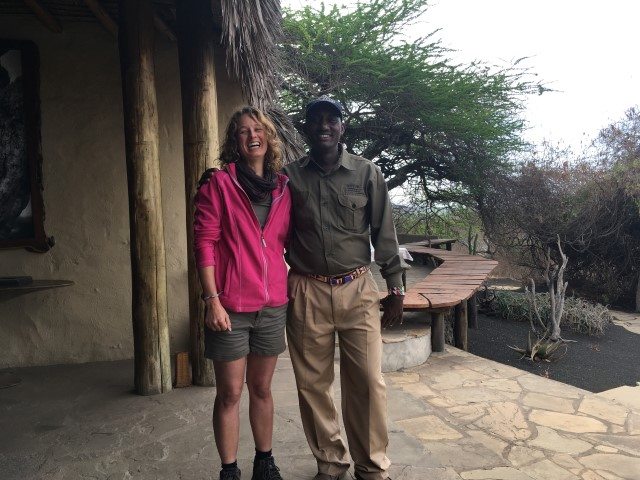

Barbara Dreyer, rhino keeper at Chester Zoo, spent time with the amazing teams that are working on the ground in Chyulu Hills National Park. Below she tells us more about her experiences and how it’s a trip she’ll never forget.

“Visiting our conservation partners, Big Life, was inspiring – watching and listening to the teams that work there was truly amazing. Everyone made me feel really welcome and some staff had even come in on their day off to meet me and share their knowledge and experiences of working with rhinos.

“Everything is run on a really hard schedule – not only to ensure these rhinos are protected but also as a safety precaution for the staff and rangers. One ranger took a call after being alerted to illegal bushmeat that was being transported down a certain road, which he then had to deal with. There’s always something going on.

“Protecting black rhino in the 21st century is incredibly dangerous for all of the protection team – it’s definitely extreme conservation! The whole experience for me was a real eye opener; seeing the level of threat to the rhinos and how passionate everyone is considering the very real risks they face every day.

“Chester Zoo’s support has enabled the teams to buy essential equipment needed to keep the area secure and provides the salaries for the rhino rangers. We felt overwhelmed – our colleagues in the field were really appreciative of our support and the support of the zoo.

“I met one rhino tracker who used to be a rhino poacher; he’s changed his lifestyle and learnt more about conservation after being approached by Big Life and is now a rhino tracker to help protect them. He’s proud of the work he does; bringing a livelihood and pride to his family and village. People now respect him for the job he does and he no longer has to live in hiding.

“One of the skills I was able to share with the protection team, is how we identify our individual rhinos at Chester Zoo and how we have categorised ID sheets for them, taking photos once a month of different parts of the rhino – left side, right side, horn, etc. – noting all their unique individual markings, ear notches and scars and looking for new marks or changes.

“I’m thrilled that I’ve been able to help develop this system at Chyulu. I’m now part of a rhino identification panel, so they send regular photos of rhinos to help identify. This process will help monitor the individuals, their behaviour and keep a note on where they’re moving around the park which is all vital in protecting them every day.

It really doesn’t cover it when you say ‘it was such an amazing experience’. I really didn’t know what to expect, I tell our visitors about our work in the wild but to then to see it, be a part of it and feel it and to see the engagement from everyone, to see how they feel…you just can’t put words on it!

“It made me feel even more proud to work at Chester Zoo, knowing how important the work we’re doing is helping.

Over the past 12 months Big Life has been working hard to get Intensive Protection Zone (IPZ) status in Chyulu Hills. The habitat is perfect for black rhinos and with IPZ status it would mean better protection for the remaining population, and possibly even enable them to translocate more black rhino to this area. The IPZ status means that Chyulu will benefit from increased support from the Kenyan Wildlife Service, including more armed rangers in the most important sectors where the rhinos are found.

The black rhino, like all other rhinos, is in serious danger; its numbers have plummeted by 90% since the 1980s. In 2011 the IUCN recognised that the western black rhino, from Cameroon and the Northern white rhino from north eastern DR Congo had both become extinct in the wild.

The eastern black rhino is hanging on to survival by a thread. Currently we are at risk of this species going extinct in the wild in just over 10 years. Places like the Chyulu Hills need continued support. ACT NOW to save the species.

Earlier this year the IUCN congress caused ripples through the conservation world with announcements of the re-categorisation of hundreds of threatened species on the IUCN Red List.

Severely affected in recent years are our closest relatives, the great apes, with the IUCN recognising that all six species are under serious threat of extinction. Four of the six ape species are now classed as critically endangered which is just one step away from extinction in the wild.

The most recent re-classifications are:

Bornean orangutan

Following an assessment led by Marc Ancrenaz, scientific director at HUTAN (our project partners in Borneo), it was discovered that Bornean orangutans are one step closer to extinction in the wild.

We’ve been working with HUTAN to protect this species for over 10 years and will continue to fight to save it before we lose it forever. Orangutans are threatened by hunting and habitat destruction for agricultural land; mainly for the cultivation of palm oil.

Join the Sustainable Palm Oil Challenge and help save orangutans.

Grauer’s gorilla

The Grauer’s gorilla population has seen a catastrophic decline; the species has seen a staggering 77% decline in less than two decades due to illegal hunting for bush-meat associated with unregulated mining in remote rainforests.

Chester Zoo’s Africa field programme coordinator has worked extensively with Grauer’s gorilla and spent 11 years conducting significant research into the ecology of the species which has been used to classify it as one of the most endangered primates in the world. Read more about Stuart’s research, and that of other collaborating partners, here.

Western chimpanzee

The Western chimpanzee is a subspecies of chimpanzee and the same species we have at the zoo. Chester Zoo’s troop contributes to a successful international breeding program. This is the first ever chimpanzee subspecies to join the list of critically endangered great apes, making our group even more important. In the wild, these chimpanzees are under huge threats from bush-meat hunting as well as extensive and increasing habitat loss and fragmentation.

All other chimpanzee subspecies are facing similar threats, are listed as endangered by the IUCN including the Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee, which we’re working to protect the in Nigeria. Over the years, we have been conducting research in Gashaka Gumti National Park, Nigeria, monitoring and protecting the chimpanzees in Nigeria to ensure this species doesn’t have the same fate as the Western chimpanzee which is edging dangerously close to extinction in the wild.

Despite all of the above reclassifications, there were several good news stories reported at the IUCN congress, including the down-listing of the giant panda from ‘endangered’ to ‘vulnerable’ as a result of a significant population increase.

That’s why we must continue to Act for Wildlife. But to do so, we need your help.

The species is endemic to the island of Java and is currently listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The species isn’t protected by Indonesian law and, sadly, its population is believed to have decreased by 50% in just over 20 years (from 1982 to 2004). It’s unclear how many still exist today and exactly where they are on the island.

As their natural habitat declines, pigs are venturing out of forests in the search for food; wandering into agricultural fields and destroying people’s crops. This has resulted in local people hunting the pigs in order to protect their produce.

Jenny Brownlie, currently in her third year of studying a masters degree in social anthropology and development, had the amazing opportunity to join our Indonesian field researcher, Shafia Zahra, in Java to support her with some of the initial research for the project.

Jenny supported Shafia on the first of five planned camera trap surveys which aim to find evidence of the last remaining wild population of Javan warty pig. Jenny tells us more about her field trip:

“As a social anthropology student, my own academic life is focused on people and the lives they lead. However, to interact with a culture so different to my own, even if through animals, was not something to be turned down!

“Having never done fieldwork before in the UK, jumping straight into fieldwork in Indonesia seemed slightly insane to anyone I spoke to. As it got closer to the departure date I began to agree with them. Being of Scottish origin, the thought of five weeks in hot humid Indonesia created two overriding emotions; unbelievable excitement to be in a country so different to my own and the fear of the unknown.

“Although having visited Java on a Scout trip, it was going to be a different experience this time round. Being by myself, rather than surrounded by 30 other Scottish Scouts, wandering my way through customs and baggage claim took less than a quarter of the time. Walking out was exactly the same, leaving an area of air conditioning to the mid-afternoon sun of Jakarta is not something any Scottish person can prepare for. After months of planning and emails sent; I was actually here and ready to begin this new adventure.

“Two days later, the real fun was about to start, kicking off with nine hours on a train. Travelling past the rice paddy fields, villages and occasionally through larger towns was extraordinary. Throughout the journey I think we passed fields at each stage of rice production.

“We arrived in Banjar at what looked like a small village station. Following Shafia towards some of the bike driven rickshaws ready and waiting at the station, our kit was loaded up and we headed for the hunter’s lodge. Pulling up outside the lodge I was surprised. I had no clue what to expect of the house itself but the location of it surprised me. Fully expecting to be living in the middle of the jungle with very limited people about I got a bit of a shock when we pulled up outside a house with others squeezed in all around it. For me it looked very similar to the cul-de-sacs that we have in the UK.

“Leaving the village for the rainforest was a mix of emotions. We headed out on scooters to start setting up camera traps. By the time we came to the fifth camera we were forced to leave the scooters beside a small hut and head to the edge of the forest on foot. The hill in front of us was terrifying. The steepness was one thing but the fact the soil was loose and seemed to crumble underfoot did not build much confidence for this being a quick drop off. Watching the hunters climb up the hill with enviable ease I was dead set against falling or sliding back down. I may not be able to climb and walk at the speed that they can in the jungle, but heck was I falling in front of them.

“By far one of the weirdest feelings was during the observation treks. Each week we went on a trek at a different time of the day. For the first week we went out 5pm – 8pm, the second week we went back out and did the same treks but from 9pm – 12am, then for the third we did the treks again but 3am – 6am. Being in the forest at 11pm at night when it is pitch black is bizarre. Yet you didn’t need it to be 11pm for it to be complete darkness. About half an hour after the sun sets at 6pm, it is total darkness. The prolonged but beautiful sunsets that we are used to in the UK aren’t really something that you see in Indonesia.

“For roughly 20 minutes the sky turns that recognisable red-orange but as soon as it arrives, it’s gone. The first night we were there was unimaginable. With a clear sky, the stars were incredible to look at. For the duration of our break half way through the trek, I don’t think I looked away once. My only complaint was the relationship between the sky and my camera. To be able to bring home a view like that and show others was something that I desired so much, yet all six pictures that I attempted did it absolutely no justice in the slightest.

“If anyone ever has any thoughts about visiting Indonesia, real Indonesia, not the bright lights alcohol filled tourist areas; I could not encourage it enough. Even if to only see a country so different from our own you will come away with an experience that will not be forgotten in a hurry. And thanks to Chester Zoo for allowing me to accompany this research.”

We can’t wait to see whether the camera traps find any results! We’ll be sure to keep you posted with any updates from the project, so keep an eye on our blog for more information.

We’re proud to be leading the way in helping to increase the population of endangered plant species, through scientific investigation and plant propagation programmes at the zoo and in the field.

Chester Zoo is home to one of the largest collection of carnivorous plants ever seen in the UK – the National Plant Collection for Nepenthes.

Many of the 160 known species of Nepenthes known to science are already on the very edge of extinction. That’s why our horticultural team is committed to protecting the future of these incredible and varied species.

We have around 130 species at the zoo and the skills and expertise of our staff is vital in ensuring these incredible species thrive. It’s important that we cultivate a key safety net population. Some of the species need plenty of heat and humidity, similar to that of the rainforests in Indonesia where temperatures can exceed 40°C and humidity 90%. Others originate from highland areas and prefer cooler night temperatures.

It takes a lot of care and attention to maintain the right conditions for these incredible plants when living in the middle of Cheshire, where temperatures and humidity doesn’t tend to get, or stay, very high throughout the year.

We recently added a new species of Nepenthes to our collection; Nepenthes rigidifolia which is another critically endangered species in the wild. There aren’t many specimens in cultivation either, making the plant even more precious!

Phil Esseen, Chester Zoo’s curator of botany and horticulture, tells us more:

“This particular species of Nepenthes is occasionally propagated from ethically-sourced plants, and the specimen we have in our collection had been grown by a specialist in Germany.

It’s important to keep this endangered species as an insurance population, as the plant is only known from one restricted location in North Sumatra, and is therefore extremely vulnerable. Following a recent visit to this site by a Nepenthes expert, it appears that the sole population of this plant in the wild may have been wiped our due to poaching.

“Keeping plants alive in safe and controlled conditions means that if anything should happen to the wild population – for example a natural disaster or the ever increasing pressure humans are putting on habitats – the plant is not lost forever. It’s so important to try and maintain as much diverse genetic material as possible (e.g. plants from different parents), so that the future populations are sustainable and can potentially adapt to changes in their environment.

“We have been working on different methods of cultivation and propagation, using some of the more common species to start with to ensure we get the technique just right! We have propagated them both by cutting and by seed and have been experimenting with different growing media.

“Looking into the future, we will be working to increase the genetic diversity, especially of the more threatened species of Nepenthes, and we hope one day we will be able to support and establish conservation projects in the field to help save this plant in its natural habitat.”

Some of the zoo’s Nepenthes collection can be seen in Plant Paradise and in Monsoon Forest, whereas the wider collection may be seen by appointment only.

Cat and Jenny recently spent time in Borneo with our partners HUTAN; meeting and seeing first-hand the work the project team are doing in the field.

Following on from the news we shared earlier this month about four Javan green magpies hatching at the zoo for the first time, we’re really pleased to share some more songbird news with you…

Our keepers caught the Sumatran laughingthrush chick’s first flight on a special nest camera after their attempts to breed the rare species proved successful. This is great news for the species as – like the Javan green magpie – it’s facing a high risk of extinction in the wild.

These birds with their beautiful song are in rapid decline. The main threat to the species is the illegal trade and trapping for the caged bird trade which is a big problem across Indonesia.

Andrew Owen, Chester Zoo’s curator of birds, tells us more:

In the wild the Sumatran laughingthrush is disappearing at an alarming rate as it has become victim to a shrinking habitat and the unrelenting demand for the caged bird trade.

“Caged birds, the vast majority of which have been harvested from the wild, can be seen just about everywhere in Indonesia – hanging outside houses, shops, restaurants, petrol stations, you name it. Most of them are kept in terrible conditions and are seen as something beautiful to admire for a couple of days until they wither away and die. As the species becomes rarer and rarer its value increases, which is beginning to push it to the edge of extinction. The sad reality is that while market places are full of the sounds of caged birds, the forests are almost silent.

“The Sumatran laughingthrush is very, very rare and to see the chick take flight for the first time on camera is incredibly special. I’ve been working with the species for 12 years and haven’t been lucky enough to witness one of these birds fledge and leave the nest before – it’s really charming footage.

Our new chick and the four other chicks we have reared this year are ever so important to the conservation breeding programme for the species, which is working to ensure a protected population for the future.

We’re also working closely with our partners at the Cikananga Conservation Breeding Centre in Java, where we’ve set up a specialist breeding centre to boost population numbers and help rescue birds from local markets. The long-term aim is to release birds into safe wild areas.

Chester Zoo is also part of a conservation breeding programme which is striving to create further safety-net populations of the species in Europe. There are currently only 70 Sumatran laughingthrushes in the European breeding programme.

Donate to our songbird project and 100% of your money will be used to help save songbirds in the wild.

The painted terrapin (also known as a painted batagur, saw-jawed terrapins or three-striped batagurs) is one of the most endangered turtles in South East Asia. It can now only be found in very small, isolated populations in Southern Thailand, the Malaysian peninsula and the Indonesian islands of Sumatra and Borneo.

We’re working with a project on the island of Sumatra in Indonesia, to help save this critically endangered species from going extinct. Alongside the SatuCita Foundation, we are working to protect what is believed to be one of the last remaining healthy populations of painted terrapin in Indonesia.

This species is currently at a very high risk of extinction, so we must do all we can to help protect it! Their numbers are so low as a result of people and predators poaching their eggs from the sandy beaches they lay them on.

In order to save the species, the project is working to increase the wild population by patrolling the nesting beaches. This monitoring is vital to securing and protecting the terrapin eggs, which are incubated and protected in situ – meaning that they’re left on the beach that they were laid on.

Hatching success

Some of the nests that were deemed to be in high risk locations are moved into specially built pens on the beach for added security and close monitoring. Joko Guntoro, founder of SatuCita Foundation, and the team were able to collect 958 eggs for protection, during the last breeding season (December to March). From this there was a 70% hatching success rate which has already given the population a welcomed boost! This is great news as in previous years, total hatch success rates have been around 30%.

Dr Gerardo Garcia, curator of invertebrates and lower vertebrates at Chester Zoo, tells us more:

“If we are to save the species from extinction then much more funding is needed in order to protect the habitat where they live. It’s the actions of a very, very small group of people like Joko that has contributed massively to the conservation of this critically endangered species.

It’s vital we support the work being done, reinforcing wild populations and working with the local communities. We have reached out to offer a helping hand – our technical skills and knowhow play an important part of safeguarding the species for the future.

After hatching the terrapins are released and monitored. Working in collaboration with local communities is a really important part of this project as they help with monitoring the nesting beaches. Many of the individuals that now help the project used to collect the eggs and are now trained to carry out the patrols. They’re also collecting vital data on the species which will provide us with a better understanding of how the turtles live.

In addition to this project, Chester Zoo is the only zoo in the UK to have painted terrapins as a safety net population in case they do become extinct in the wild. By monitoring the species at the zoo, this information can also feed into the work we’re doing in the wild.